I really hate those television shows that feature reunions between adult adoptees and their birth parents. The Learning Channel's entry in this tear-stained derby, a show called "Reunion," is the worst. In each episode, they plod through years of buildup and anticipation, tugging heartstrings with murky photos of the biological parent when they relinquished their child and baby pictures of the adoptee. We see letters that were never sent and arty footage of each person staring dreamily out a window. Inevitably, it all culminates with a tearful reunion, garnished with roses and balloons.

It's not that I'm completely unsentimental. But those shows irritate me because they have motivated a generation of adult adoptees and birth parents to believe in that perfect reunion -- the meeting that will fill all the voids in their lives, resolve all of their feelings of inadequacy, assuage all their guilt.

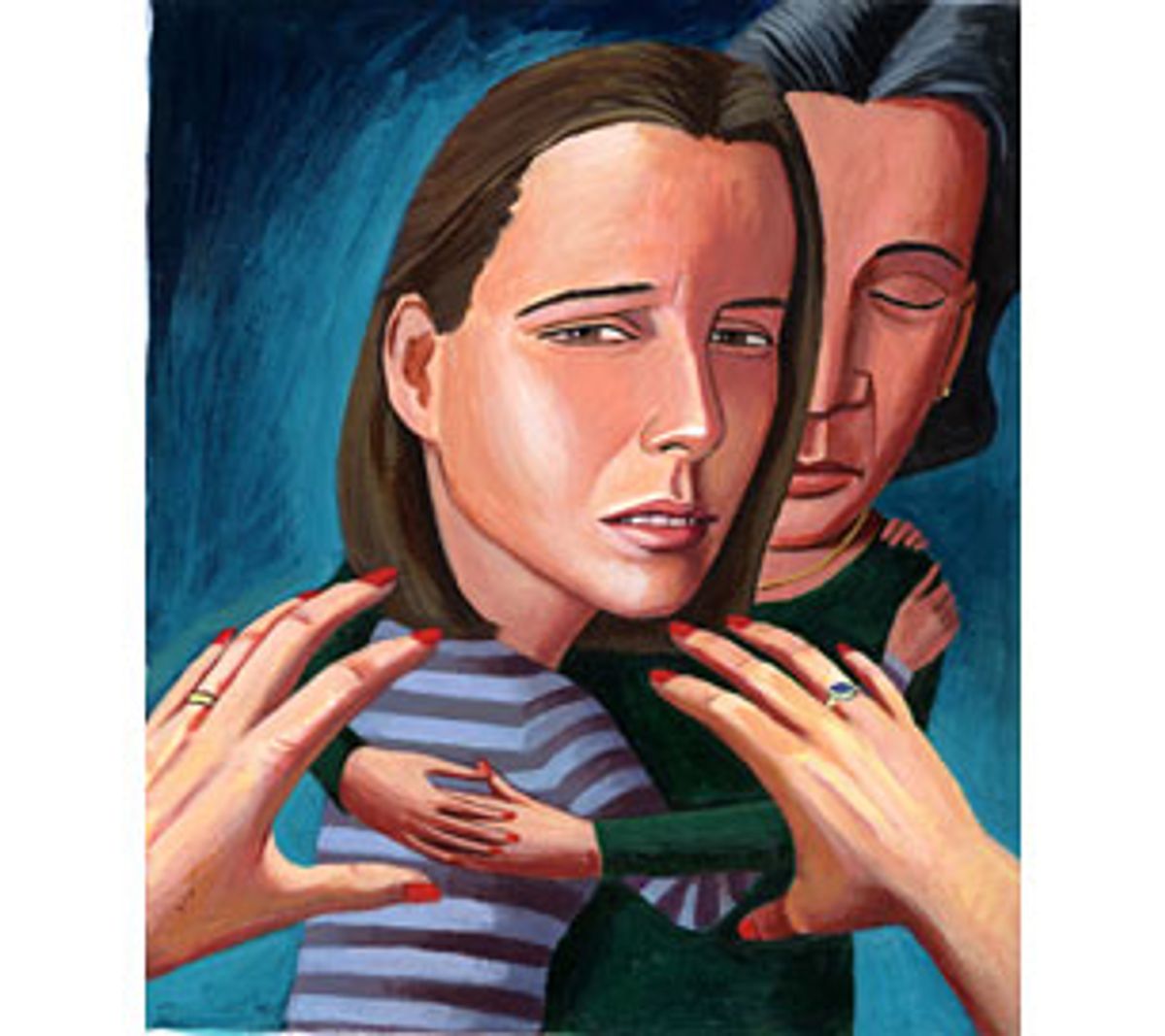

In fact, this image of divine reconciliation has fueled the voters and lawmakers of a growing number of states to amend adoption laws to allow adoptees access to their original birth certificates or their adoption records. A countermovement, comprising mostly birth mothers who entertain no fantasies about meeting the children they gave up for adoption, has grown in response, creating a deadlock on the issue, mostly in court.

In Tennessee and Oregon, open-access laws faced court challenges before they even went into effect. The Tennessee law was ultimately upheld by the state Supreme Court, but in Oregon, where a group of anonymous birth mothers opposed to open access lost their battle to strike down the law, the state Supreme Court may reconsider its decision and could issue a ruling as early as this week.

These laws make the assumption that every child who was given up for adoption burns with an overwhelming desire to meet, and fall in love with, his or her birth parents. Even the birth parents who oppose open access use this argument, believing that without legal protection they will surely be tracked down and exposed by curious birth children.

Did it not occur to anyone that there are some adopted children who aren't interested in finding their birth parents? That some adopted children might want some guarantee that they won't be hunted down by their biological parents? Shouldn't they be entitled to a choice about who will barge into their lives and make themselves at home?

I was adopted as an infant on the Friday before Mother's Day, 1970. My adoptive parents were assured that the records would be forever sealed, and that no stranger would ever show up on their doorstep and claim their baby as their own.

Eighteen years later, I received a thick envelope in the mail. I lived in Indiana and the postmark was from California, so I assumed it was from a camp friend. I tore it open, and a handful of pictures spilled out.

I didn't recognize the brunet woman smiling at me in those snapshots, taken over a period of two decades. There she was in high school in the '70s with a middle part and long straight hair, and then in the early '80s, with big puffy hair and lots of eye makeup. And there were more recent photos too -- professional, on glossy paper with vibrant color. Who was this woman?

The letter explained it. "I believe you are the baby girl I gave up for adoption in 1970." Whoa. "Mom! Look at this!" My mom joined me at the kitchen table. Together we read the letter and stared at the pictures.

"She looks nothing like you," my mom said. (She was right.) "How could she do this when she didn't even know if we'd told you that you're adopted? Why didn't she contact me first?" There was fear in my mom's questions; I could hear it. I shoved the letter aside.

At age 6, when I first learned I was adopted, I cried and cried, not because I wanted to know who my birth parents were, or because I felt lost or empty, but because I wanted to have been born to my parents. I loved them so completely that I didn't want any mysterious thing out in the world to mean that I was less a part of them.

They pulled me into a tight family hug and assured me that I was even more a part of them, because of all the babies in the world, they chose me. They said we were meant to be together as a family.

I never felt like anything was missing, and I had only idle curiosity about my birth parents. My grandpa thought I looked like every famous blond on television, from Chris Evert Lloyd to Jane Pauley to Princess Diana, so sometimes I wondered if I was biologically related to someone famous. It was a fun fantasy, and a pretty common one among the adoptees I knew. But even as a teenager, when I believed my parents were the most embarrassing, uptight, rigid authority figures on the planet, I never wished for different parents, even birth parents.

As we read the letter that day, days before my 18th birthday, it seemed too personal, painfully so. It was filled with details of the woman's life and her desire to know me. She wanted me to call, to write, to share the details of my life with her.

My mom and I agonized over what to do. My parents knew only a few details about my birth family, and there wasn't enough in the letter to know for sure whether this woman was really my birth mother. My head was spinning with curiosity and fear, and from trying to fit this bizarre new piece of my life into the puzzle of my everyday existence -- calculus finals, term papers due, my senior trip and planning for the prom. My mom suggested I skip school the next day, and that we go to the adoption agency to find out if what the letter said was true.

I called the number on the last page of the letter, and told an answering machine that I had received the letter and that I would appreciate it if this woman (I'll call her Mary) didn't contact me again. I told the machine that I needed to find out if Mary really was my birth mother, and until then, I didn't want to be in touch with her.

She phoned five minutes later.

Mary was a deluge of questions -- first, she wanted to verify that all the details fit, which, for the most part, they did. Then she wanted to know what I'd been up to for the past, oh, 18 years. The one question that kept drumming through my mind was,

Is she or isn't she? Even though the details matched, I kept thinking that there must have been more than one baby girl born on my birthday who was given up for adoption. At the same time, I was curious to hear Mary's story and to find out who she was and why she gave up her baby.

Mary said she and her boyfriend were 16 when she got pregnant and they both wanted what was best for their baby. As I listened to her talk lovingly about the baby she gave up, I was thinking in the abstract of a hypothetical baby, not that the baby could possibly be me.

It was too surreal, this stranger believing that she was part of my life, conveying the most painful parts of herself to me during our first conversation. I was embarrassed, because she was too interested in me, and because she was showing me all of the carefully sewn seams in her life, which now seemed to be unraveling as she revealed all of her secrets.

Apparently she took a long and complicated path to find me. She had first started attending meetings of Concerned United Birthparents, an advocacy group for birth parents. CUB led her to a Michigan detective who specializes in finding adopted children. He came up with my name and an incredible amount of information about me, including my SAT scores and my yearbook pictures.

As she recited all of my vital statistics to me, I began to feel uncomfortably exposed, like in those dreams where you show up at school wearing nothing but a too-small washcloth. As we hung up the phone that night, Mary told me that she loved me. I felt queasy, the way you do when a lover says those words too early and you don't feel the same way. I muttered quickly, "OK, bye."

The next day, I skipped school, and my mom and I drove to the adoption agency that had placed me to see what we could find out. Amazingly, the same caseworker was still there; even more incredible, she remembered my family. But the law at that time prohibited us from finding out the names of my birth parents without a court order, so we were stuck.

Back at home, I called Mary and told her that I couldn't find out for sure if she was my birth mother. I asked her not to contact me again because it seemed strange to start such an intimate relationship with a total stranger. She asked if she could call, just every once in a while, to see how things were going with me. I said OK, thinking that if she was my actual birth mother, I didn't want to push her away entirely. I imagined that I would treat the calls like rare communications with distant relatives: "Hi, how are you?" "I'm fine. I'm getting ready to go to camp again this summer." "Really? Great. Good luck with that." "Thanks, bye."

It seemed as if she called constantly, not because her calls were frequent but because they were so intense. I couldn't hang up no matter how much I wanted to -- Mary had a million questions and a million things to tell me. She would tell me over and over again that she hadn't wanted to give me up, that she loved me, that she thought of me all the time, that she had always loved me.

I tried to answer her questions about my life, but I found myself feeling more and more invaded, as if layer by layer she was trying to get to the root of me, and she was still, in essence, a stranger. I didn't want to upset Mary, in case she was my biological mother, but her phone calls were overwhelming for me, and disturbing to my parents, who were concerned that all this emotional baggage would disrupt my final months at home before leaving for college.

Because Mary perceived, correctly, that my mom didn't like her calling me so often, she would lie to my mom about who she was. This heightened my mom's panic about another mother moving in on her child, and her mama-bear instincts kicked in.

One night, after Mary had lied to her about who she was, my mom picked up the phone while we were talking: "I really don't appreciate you lying to me about who you are. I know who you are when you call." Mary: "Don't feel threatened just because I gave birth to Beth." Mom: "I don't feel threatened, because I am her mother. I would just appreciate some honesty." At that point, I hung up.

The next time Mary called, I asked her to back off. She responded by telling me that she had ordered copies of my high school graduation pictures and would be coming from California for my graduation. Would I meet her?

I agreed to meet her after my graduation at her aunt's home nearby, thinking that maybe by meeting her I could figure out whether she was my biological mother. Also, I was curious. My mom didn't think it was a good idea -- she was concerned for my safety. But she didn't forbid me from going. She had begun to see Mary as a stalker, convinced that she might kidnap me and whisk me away to California. (Considering Mary's manic ardency, it was not a far-fetched scenario.)

I brought my then boyfriend, who was also an adoptee, along for moral support. We drove to a tiny bungalow in an older neighborhood. Mary answered the door and immediately reached out to hug me. She looked like her pictures and talked to me the way she did on the telephone. She introduced her aunt, who hugged me, too. I felt immediately uncomfortable, awkward and out of place. I was being embraced like I was family by people I didn't know.

Mary brought out a folder full of photos of her family and the family of the man she identified as my biological father. I was glad to have something to focus on. Together we looked for resemblances. We were reaching -- this jaw line resembles mine, this hair color. But there were no clear answers, no obvious signs.

I guess I was hoping that someone in those pictures would be a mirror image of me, so I'd know, finally, and for sure, but nobody was. Mary stared at me. Every once in a while she would touch me, or tell me that she loved me and couldn't believe she was finally in the same room with me. She was weepy, too, telling me again that she hadn't wanted to give me up.

She wanted me to hug her, she begged me to stay in touch with her, she pleaded for pictures -- baby pictures especially. The closer she tried to get to me, the more distance and fear I felt. I wanted to leave, but she wanted to take photographs of me. Finally, emotionally drained, we left.

When I went off to college, she continued to call. Most often it was in the middle of the night, and I would answer the phone deep in the foggy netherworld of half-sleep to hear her shaky voice trying not to cry. "I had a dream about you, that something bad happened. Is everything OK?" I reassured her that I was fine, but asleep, as was my roommate. I asked her again to back off. I came to dread picking up the phone and hearing her voice.

She sent me presents: giant packages filled with stuffed animals, vitamins, perfume, candy and postcards pre-addressed to her. She wrote me long chatty letters detailing the minutia of her life. She begged me to send her a postcard a week, just to let her know I was OK. Every once in a while, I would send her a postcard or call, but I always felt awkward about it -- like I was trying to humor a stalker to keep the hunting from getting any worse.

She was getting more and more needy, more obsessed; she told me her apartment was a shrine to me. She had blown up the photos she took when we met and hung them, along with the high school and prom pictures she had managed to get, all over her place. She told me she was coming to see me at school.

I worried about it for weeks. I didn't want to see her, but didn't know how to tell her that without devastating her. It was getting to be too much. Her clinginess repulsed me; I was emotionally plagued by her constant intrusions. I finally became convinced that I needed to "break up" with Mary.

The phone call took an hour. She sobbed the entire time I spoke. She called me her baby and told me she didn't understand how I could do this to her. Couldn't she just check in on me every once in a while? Couldn't she still come to see me, one last time? I tried to stay calm and consistent, tried to achieve the conversational equivalent of backing away slowly, making no sudden moves. When we hung up, I knew it wasn't over.

A year later, I was working at an internship in downtown Chicago. I was walking to the el station when a man jumped out of the crowd walking in the opposite direction and snapped a photo of me. He was instantly absorbed by the crowd.

Two weeks later, Mary called me at my internship. She had hired another detective to find me, convinced that I was sick or dead or in some sort of trouble. The detective had been to my apartment, had supposedly spoken with my roommates, had figured out where I worked and had taken pictures of me.

Mary had another reason to call this time. She repeated a convoluted story she had told me before about giving birth -- to me, theoretically. She said the doctors told her that the baby had a simian crease, a horizontal line across the palm that is common in children born with Down syndrome. I don't have the crease and that had always bothered her.

Now Mary wanted me to give blood for a DNA test so she could be sure that I wasn't switched at birth. I was so cynical about the whole mess that it sounded to me like another way for her to prove that I was her biological daughter. I was afraid that if I took the test and it proved that she was my birth mother, she would become even more forceful and scary. I would no longer have an excuse to keep her away from me.

I told Mary I wouldn't take the test, that I was angry about the detective she sent to spy on me. I really didn't care if I was switched at birth and my biological parents were floating around somewhere out there. For me, one biological parent -- this one, certainly -- was already more than I wanted in my life.

We've done this dance several times now. She called me when she read in the newspaper that I was getting married. She called me when she gave birth to a baby boy, wanting to know if I was interested in meeting my "half-brother." She called me on my 25th birthday. Each time, she would sob and tell me she missed me, she loved me, she absolutely had to call me, she hoped I understood.

She seemed so distraught, so obsessed and so demanding of my time and attention that it was just too overwhelming. Whenever I talked to her for too long or let her in on too much, she was back, full force, with cards, letters, photos and phone calls out of the blue.

I could have told her that I do feel grateful that she chose to have me, that she chose to give me up. I know she made a tremendous sacrifice -- she's obviously still suffering from it. But I knew that one simple admission might touch off a new, suffocating avalanche of attention and fixation.

When she called my husband and lied about who she was in order to talk to me (I had told him I didn't want to talk with her), I decided I'd had enough. I wrote her a letter telling her that I couldn't cope with her lack of respect for my privacy. I told her that her random weeping phone calls and endless letters were upsetting and disruptive.

I asked her to show me that she understood me by letting me go, by not contacting me, not even to respond to the letter. I told her that I didn't know if I would ever contact her again, and not to count on it.

That was five years ago. I haven't heard from her since.

Families are complicated, messy and primal. It takes years for children to fully embrace and understand all of the secret beauty and ugliness in their kin. The texture and rhythm of each family are so distinct that no matter how close or divided the family becomes over time, that primordial beat thumps through every sacred moment of a life. That thump is sweetness and bliss for me, and it consumes every need and every urge I have. My parents and I are so tightly bound to each other that I can't breathe without feeling their love within me.

Perhaps I am too selfish, too self-absorbed or too afraid to add another family to my life. Maybe things could have been better if it hadn't felt so forced, or if I had felt like she understood me better, including my need for privacy and safety. I never believed that she would hurt me, but having her repeatedly thrust herself into my life made me feel violated in some confusing, intangible way.

I know that some reunions work out. I have friends whose birth parents were able to pick up where they left off, and who never felt invaded or uneasy about the intimacy called for when adding a birth parent to their lives.

One friend found that his mother and his birth mother share the same name and look like sisters. He danced the first dance of his wedding with his mother and his birth mother, the three of them clinging to one another, heads pressed together.

But that type of harmony is rare, and it's almost never immediate. If it can occur at all, it's more often something that's built, through time and trust and hardship and endurance, the same way all lasting relationships are.

To believe that blood ties alone can bind a family goes beyond the clichi of blood being thicker than water to assume a miracle. Sure, it's possible that the long lost can be suddenly found and reclaimed in a hail of tears and kisses, but it's not something I'd count on, no matter how many times you've seen it on TV.

Shares