"Nobody writes them like they used to, so it may as well be me," sang Belle & Sebastian's Stuart Murdoch on the band's first proper record, "If You're Feeling Sinister" (1997). He delivered the line with a modest shrug, but for some listeners -- mainly grown-up boys and girls who still took solace in Smiths records -- it sounded like a manifesto.

Murdoch himself could have been the subject of a song off the Smiths' "The Queen Is Dead" -- a church janitor who likes to wear silver trousers. And his seven other bandmates from Glasgow, Scotland, also seemed to know what Morrissey and Marr knew back in the 1980s: that even if your pimples clear up and your braces come off, the world can still pinch like the wrong shoes. With such lilting anatomies of melancholy as "Lazy Line Painter Jane" and "Stars of Track and Field," Belle & Sebastian made a virtue of that sort of wallflower wit.

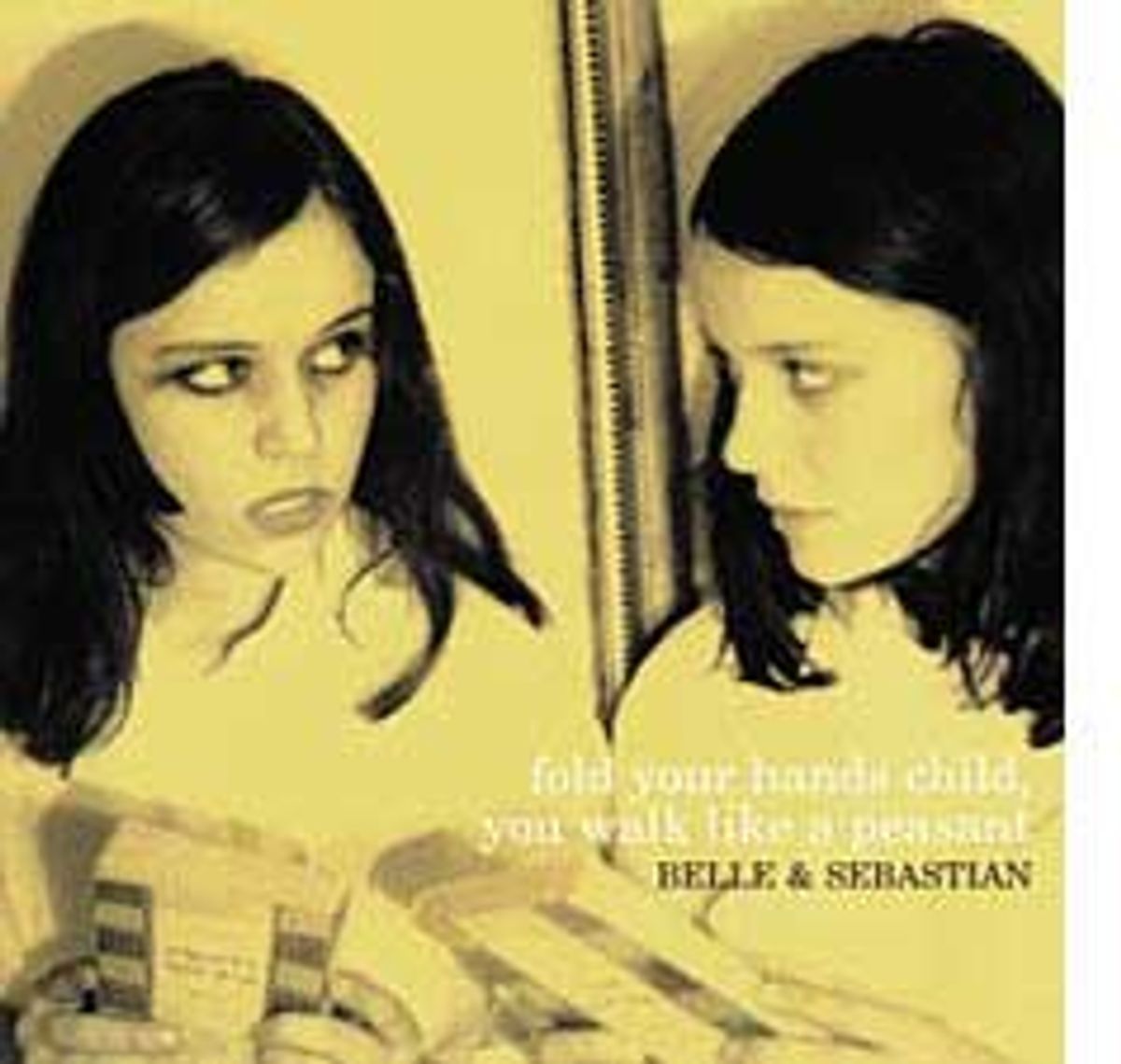

On "Fold Your Hands Child, You Walk Like a Peasant," the band's fourth record, strings, flutes and trumpets filigree pristine melodies. The result, as on their earlier albums, has all the rock 'n' roll kick of a teacup rattle. But that beloved wit is rare: Murdoch and the band seem tired of consoling with tragicomic parables of boys who need to put the book back on the shelf and girls who have split ends and VD. They almost sound determined not to be the poster children for unforgivably fey sensitivity -- the role they played in the film "High Fidelity," in which a concave-chested record store employee was mercilessly razzed for listening to one of their records.

Instead, the album features an "issue" song ("The Chalet Lines," about a girl who's been raped). And Murdoch's given up the winking references to dirty dreams for sex itself, a development reinforced by the sinuous, suggestive string section of "Don't Leave the Light on Baby." Like the nine other compositions, both songs are slow of tempo and devoid of the irony and insouciance that made Belle & Sebastian semi-famous among record store employees and their friends. For the first few spins, the new angle makes for an infuriatingly soporific and chilly listen.

Which isn't surprising. The last full length, "The Boy With the Arab Strap," found the band in a rambling, diffident mood, unwilling to deliver -- as they'd done on "Tigermilk" (the actual debut record reissued last year), "Sinister" and several EPs -- instantly charming songs that were as wry and flushed with feeling as a just-confessed crush. But "Fold Your Hands," with arrangements that are less music-box cutesy and more considered in their use of retro touches, is again a more polished attempt at ditching their rep as pent-up and way too precious.

The most affecting numbers -- "I Fought in a War," "The Model," "There's Too Much Love" and "Women's Realm" -- are all elegant, torchy songs that temper regret and befuddlement with resolve. They're rather grown-up, and they're all Murdoch's doing. The songs written by the other members of the band don't fare so well. The music for cellist/vocalist Isobel Campbell's "Beyond the Sunrise," is a lovely exercise in eerie acoustics, but her borderline hokey lyrics put wayward women in soft-focus ("Sir, come to me and I will keep you warm/Taste hope in my skin and faith with the dawn"). Coming from baby-voiced Campbell, the words just sound sentimental and naive. And violinist Sarah Martin's first contribution, "Waiting for the Moon to Rise," is pretty, but it's basically just a standard folk-pop ballad about longing.

There is nothing wide-eyed or ordinary about Murdoch's "Women's Realm," a serenade to a girl who'd rather hide out in a train station with a flashlight and homemaker magazines than face the world. Murdoch's choirboy tenor pipes along, agile as a flute, as he moves through Glasgow, down silent streets, along the river and over to an empty dance hall where he dreams about "a boy, a girl, a rendezvous." He's unsentimental about their prospects, but not hopeless. "Are you coming or are you not?" he demands. "There is nothing that would sort you out/There's nothing I could say or do/You're going to crash, I'll set the bails in front of you." It's a new tenderness for the band, a state of grace achieved without cheek or irreverence. On another record, it could be the start of a brilliant career.

Shares