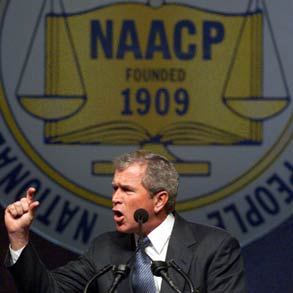

With his racist pals thousands of miles away and his unseemly South Carolina primary campaign almost five months behind him, Texas Gov. George W. Bush addressed the 91st convention of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People Monday.

That made him the the first GOP presidential candidate to address the group since his father in 1988. But Baltimore calls itself “the City that Reads,” not the city that appreciates pretty pictures of Bush with little black kids. After the speech, many members of the NAACP didn’t seem to think the Bush campaign’s photo-op talent and rhetorical vagueness would be enough to sway their members come November.

Bush was folksy and charming, and spoke strongly about how, since the historic desegregation in 1957 of Little Rock (Ark.) Central High School, “all can enter our schools, [but] many are not learning there.” But while Bush was received politely, Gary Bledsoe, the NAACP Texas state conference president, said, “I heard whispers throughout wanting more substance.”

Four members of the audience weren’t whispering, however, when they interrupted the introduction to Bush’s speech to stand and shout that Gary Graham, a convicted murderer recently put to death by the state of Texas, was innocent. “An innocent black man was killed, executed by George Bush!” one of them yelled as they were led out of the auditorium.

Back in Austin, Texas, Bledsoe also has raised his voice against Bush over the Graham execution — and over the fact that 60 percent of the inmates on the state’s rather active death row are minorities. Bledsoe and the national NAACP have hammered Bush for his refusal to take a position on a hate crimes law in Texas in honor of James Byrd Jr., the 49-year-old black man who was chained to a truck and dragged three miles to his grisly death in 1998. They’ve also complained to him about the presence of plaques in the Texas Supreme Court Building bearing the Confederate battle flag and the Confederate seal.

But Bush is an artful dodger. He has never actually stated his opinion about the “hate crimes” bill. “I’ve always said that all crime is a hate crime,” Bush has said. And though the NAACP asked him to remove the Confederate symbols from the state building in January, he waited until June to do so — long after the GOP nomination was sewn up.

While stumping in South Carolina before that state’s Feb. 19 primary, he seemed to have a different opinion on the matter. “In our state of Texas, you know, when we see the Confederate symbol on the Capitol, we view that as that was a part of our history, a part of Texas history,” he said to a South Carolina TV station. “And, you know, that doesn’t mean any of us embrace slavery, but it’s a part of the history of our state of Texas.”

When asked about the NAACP’s tourism boycott of South Carolina due to the Confederate flag flying above its Capitol, Bush said that “my advice is for people who don’t live in South Carolina to butt out of the issue. The people of South Carolina can make that decision.”

Bush didn’t tell the NAACP to “butt out” today, of course. He appears to hope that the race-, Jew- and gay-baiting campaign he and his allies waged in South Carolina almost five months ago will now be nothing more than a distant memory, if that. In the last couple of weeks, he has spoken to the Congress of Racial Equality, the League of United Latin American Citizens and the National Council of La Raza.

“I’ve been looking forward to this,” Bush said to the NAACP. “I’ve been looking forward to coming here and tell you … what’s in my heart.”

Acknowledging that “the party of Lincoln has not always carried the mantle of Lincoln,” Bush proposed providing education for every child, and for increased federal support for faith-based charities. “I believe we can find common ground,” he said. “This will not be easy work. But a philosopher once advised, ‘When given a choice, prefer the hard.’ We will prefer the hard because only the hard will achieve the good.”

“My governor is respecting us with his presence,” said Herb Powell, a member of the NAACP national board who lives in Houston. Desperate to say something nice about Bush, Powell offered that at least Bush hadn’t tried to dismantle affirmative action programs like his brother, Florida Gov. Jeb Bush, has tried to do in his state.

When Jeb was asked, in 1994, what he would do for African-Americans if elected governor of the Sunshine State, he said, “probably nothing.” According to Bledsoe, that’s pretty much his older brother’s record as well. “I don’t think he won any votes,” said Bledsoe after the speech. “But at least he got people to look at him in a different way.”

And what way is that?

“He’s not a person to be despised.”

“This is a pleasant fella,” fumed Del. Eleanor Holmes Norton, the Democrat who represents Washington, D.C. “But at an NAACP convention, it’s not personal, it’s political. If he thinks that’s all it takes … I mean, I didn’t hear him discuss a single one of those issues” highlighted in the NAACP’s legislative report card, including the need for more teachers, increasing the use of background checks on gun buyers, increasing the minimum wage and passing a “hate crimes” legislation.

Holmes said she didn’t really accept Sen. John McCain’s post-campaign mea culpa for his primary-era refusal to take a position on the Confederate flag — “We don’t want to hear from you after the campaign,” she said — but did say that today would have been an opportune moment for Bush to address his appearance at Bob Jones University. He should have acknowledged that when he addressed the students and faculty at Bob Jones on Feb. 2, he should have spoken out against the school’s ban on interracial dating. But he didn’t, she said.

“I would have at least brought that one up,” she said. “Since he called the word ‘racism’ out, one way he could have shown greater sensitivity is by saying, ‘If I would have gone there again, I would have spoken out against'” the ban.

This would have been especially appropriate since Bush did apologize to leaders of the Catholic Church for remaining silent at BJU in the face of the college’s anti-Catholicism. Bush even defended the anti-interracial dating policy at one point, saying that he wasn’t sure it was rooted in prejudice.

A reporter pointed out to Holmes that Bush pledged to enforce civil rights laws, and acknowledged that “racism, despite all our progress, still exists.”

“‘Enforce civil rights’? What does that mean?!” Norton asked. “And we’re supposed to be appreciative that in the year 2000 there’s a candidate for president who’s against racism?”

It’s unfair to say Bush avoided any discussion of substance. He went back a ways — 138 years, actually — but he did find a Republican-initiated legislative accomplishment to herald, invoking Lincoln’s Homestead Act.

Bledsoe says he’d never heard Bush pledge to uphold civil rights laws before, though he doesn’t “think the governor’s been a strong advocate of civil rights in the state of Texas … I hope he’s sincere with it.”

It’s easy to question the sincerity, however, when Democrats are standing at your table, quick to mention Police Chief Charles Williams, who Bush had appointed presiding officer of the Texas Commission on Law Enforcement Officers Standards. In April, Texas newspapers publicized a 1998 deposition Williams gave in a case where a black officer had sued both Williams and the city of Marshall for discrimination. In the deposition, Williams is quoted saying he didn’t think the term “porch monkey” was offensive, and that 50 years ago, blacks didn’t mind being called “nigger.” Bush called for an apology, but not for his head. Williams soon resigned due to poor health.

Also on the Democrats’ list of ugly Bush allies is a pro-Confederate flag, pro-Bush state senator from (where else?) South Carolina named Arthur Ravenel, who during the primaries called the NAACP the “National Association of Retarded People.”

Called upon to repudiate Ravenel’s remarks, Bush called them “unfortunate name-calling.” Should Ravenel apologize? “It’s up to the senator to do that.” During the January 5 debate in Iowa, however, when pressed by fiery commentator Alan Keyes and with the whole world watching, Bush summoned a stronger opinion. “His comments are out of line, and we should repudiate them,” he said.

Bush doesn’t like to criticize his buddies. When his Louisiana campaign chair, Gov. Mike Foster, was fined $20,000 for hiding the fact that he purchased campaign mailing lists from Klansman David Duke — presumably for use in his race against a black congressman — Bush refused to condemn Foster, calling him a “good man.” He claimed not to know anything about the scandal. Then, when asked about the matter a week later, he simply didn’t answer the question.

But there is more than just a few unseemly associates to raise the question of how successful Bush would be as any sort of racial healer. After James Byrd’s death on June 7, 1998, Bush kept a fairly low profile on the murder — sometimes bordering on the clueless, if not callous.

Bush didn’t attend Byrd’s funeral, claiming that doing so would create a “highly charged political event,” though Republican Sen. Kay Bailey Hutchison attended. After a spokeswoman claimed that Bush had called Byrd family survivors to express his sympathy, members of the Byrd family disputed that claim.

An even more disconcerting event took place behind closed doors after Byrd’s daughter, Renee Mullins, flew from Hawaii to lobby Texas legislators on the hate crimes bill that bore her father’s name. After initially refusing to meet with Mullins, Bush finally agreed, but only to give her a reportedly chilly reception.

The cluelessness extends to his staffers. As pointed out in Tuesday’s Trail Mix, on the same day that Bush was addressing the NAACP, his campaign back in Austin thought it appropriate to bash Vice President Al Gore’s “attempt to … portray himself as Harry Truman” by rolling out Sen. Strom Thurmond, R-S.C., to quip, “Mr. Gore, I knew Harry Truman. I ran against Harry Truman. And Mr. Gore, you are no Harry Truman.”

Thurmond, of course, ran against Harry Truman in 1948, splitting from the Democratic Party to run as a segregationist “Dixiecrat.” Thurmond would go on to fight Truman’s civil rights efforts, going so far as to filibuster for 24 hours against the 1957 Civil Rights Act, setting a Senate record.

Isn’t there a disconnect in the Bush campaign quoting a one-time segregationist, specifically talking about his segregationist presidential campaign, on the same day that Bush is trying to reach out to African-Americans? “No,” says Bush spokesman Ray Sullivan, “Senator Thurmond is responding specifically in a tongue-in-cheek fashion to the latest Al Gore reinvention.”

But none of it really matters. In the back of the room stood Bush’s media guru Mark MacKinnon, videotaping every second of Bush’s self-effacing quips that “the NAACP and the GOP have not always been allies,” his proclamation that reading “is the new civil right,” and his references to Abraham Lincoln, W.E.B. Du Bois and Jackie Robinson.

Most likely, they’ll be coming soon to a television near you, especially if you’re a white swing voter who at least will like the idea of Bush reaching out to minorities. Still, when given a chance to really talk about race, Bush doesn’t quite seem to “prefer the hard.”