Liza Dalby’s “The Tale of Murasaki” is a coolly elegant summer read, the kind of book that, like certain Victorian novels, transports its readers to another world — in this case, 11th century Japan. The heroine, who is called by the nickname of her most famous female fictional creation and whose real name is unknown, wrote “The Tale of Genji,” a work that holds approximately the same place in Japanese literature that Shakespeare does in our own. “The Tale of Genji” describes the amorous adventures of a prince so dashing that the entire imperial court of Lady Murasaki’s time fell for him, hard. Genji’s popularity earned Murasaki her own place in the court, where she found a world quite different from the dazzling one in her stories.

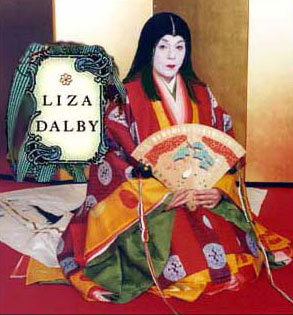

Dalby knows something about getting along in unfamiliar environments herself. An anthropologist who also plays the shamisen (a Japanese musical instrument), she is the only Westerner ever to become a geisha, an experience that became the basis for her doctoral dissertation and later a book, “Geisha.” Salon reached her by phone in her home in Berkeley, Calif.

Where did the idea for this book come from?

It grew out of my nonfiction work on geisha, which got me interested in kimonos, which is what my second book is about. Kimonos almost have a language of its own. I became totally fascinated by the 11th century fashions, the layering of colors, and that brought me back to Murasaki Shikibu. But I’m not a historian or a specialist in Japanese classical literature — people make their careers on three sentences of Murasaki’s work — I know I couldn’t contribute anything scholarly. That’s what made me think of trying a completely different approach. In a sense I did field work in my imagination.

Was there something special for you about the 11th century in Japan?

It was the golden age of Japanese courtly culture. It was a world where beauty ruled and people exchanged these poems the way we exchange e-mail, just a really heightened aesthetic sensibility that crumbled 100 years after Murasaki because the country fell apart due to internal warfare. It was only later that you get the shogun and the samurai; the usual stereotypes that we have of Japanese culture are more from that later period.

Was the 11th century a particularly good time for women?

It was also a golden age of women’s literature, with these court ladies. The position of women fell quite considerably after Murasaki’s day. When you have a society in which military values are paramount, those are the societies where women’s positions tend to be very low. They could inherit property in Murasaki’s day, and that changed.

In some ways, the world in your novel reminds me of the one we find in 19th century British novels.

I hadn’t thought of that, but it’s true that in Murasaki’s time the women had the kind of rich interior life that they often have in Victorian literature. You’ve got educated women with a certain social position, but also very circumscribed. They didn’t have the freedom of movement that the men had. Even so, the cultural aspects of life were so important, for men also. For a man, it wasn’t how strong he was or how good a warrior, but how good a poem could he write, how sensitive he was. Her hero, the shining Prince Genji, is the epitome of the ideal male of that period, and he’s no samurai!

He’s elegant and passionate, but he’s not the chivalric knight of the West.

No, but he’s not a Don Juan lady-killer either. Genji has lots of lovers, yes, but one theory is that Murasaki wrote it that way because she was interested in the various positions women find themselves in emotionally and socially. Her female characters are a lot more interesting, and as the shining prince comes to know these ladies, so does the reader, and we see how they cope with their situations. But Genji isn’t cardboard either. You see him mature as a character also.

Murasaki was hesitant to get married.

She resisted it for a number of years. If you were a woman, you had a certain amount of choice in these matters. A man’s position, how far he could rise in the hierarchy, depend on his wife’s name and the financial support of her house as well.

How much of what you depict is part of the historical record?

I can tell you in a nutshell, but I have a Web site that’s an addendum to the book. One of the pages is a very detailed essay called “Fact and Fiction in ‘The Tale of Murasaki.'” Writing it I kept thinking that the things that people will think are very modern observations, things they’ll be sure I’ve made up, those are all hers. They’re things that you’d never dare to make for fear they’d seem out of place. The historical material mostly comes from a diary she kept while she was in court service. That throws a very bright spotlight on a lot of details for about five or six years: ceremonies in court, description of dress and people’s characters. It’s fragmentary and hard to read as a narrative, but it’s a wonderful source in that respect. She doesn’t say anything about her early life, or her husband, who was then dead, or her daughter.

The other source I used was her poetry collection. Literate people would save some of the poems that they had exchanged with others — these poems really were a form of communication. It really was like e-mail in more ways than you might think. Most of it was pretty ephemeral, but people would save some of it, along with a note about the circumstances under which it was composed: “I wrote this poem to so-and-so on the occasion of someone bringing me a branch of cherry blossoms,” that sort of thing. So we know a little bit about it. I’ve worked most of the poems from her collection into the text by using the notes as hints and then imagining what sort of situation she could have been in that would have culminated in writing this poem. The poems are all hers, and they’re touchstones throughout the book.

It’s an oblique communication. The poem will be about something in the natural world, something like ice melting in the mountains, but the meaning communicated will have to do with the relationship between the sender and the recipient.

It’s as if nature becomes infused with human emotion and many of the metaphors hark back to earlier poems that everyone knew. That’s the problem with translating them. Her readers would have this huge base of linked references that they all know so they wouldn’t have to state them. A poem could be very short and very elliptical and you know that the readers were making all these associations. They’re practically impossible to translate. You get this little tiny poem and then two pages of explanation. I didn’t even try to be poetic. I’d emphasize one reading that could be found in the poem, but you lose all those other echoes and reverberations.

The clothing, the robes had the same sort of significance.

An outfit that you would put together would almost be like a poem. All the colors you would put together would have poetic references as well. When people translate “The Tale of Genji” or other 11th century works into English, they come across these descriptions of clothing, and they cut great chunks of it because they think it won’t make any sense to modern readers. But my position, and this is where the anthropologist comes through, is that if they were interested enough in these things to write about them, they must have been meaningful. To the people reading these descriptions, it must have been conveying a lot of information. I included a lot the clothing information but tried to work in some sense of how it would have felt if you were, say, wearing gray mourning for a year. Coming out of that and suddenly putting on bright colors, how that must have expressed the changing status of your life.

What are some of the meanings to be found in a kimono?

Well first of all, they weren’t personal meanings. They were more attuned to the seasons and to the occasion. By showing yourself to be aware of the seasonal changes and in layering the colors correspondingly, you’d show that you were a sensitive person. Being very susceptible, very sensitive to nature, that was the highest, what a person should aspire to. And the epitome of that was the fictional Prince Genji.

Clothing was just one aspect of this. Women and men also would make incense blends. You could be judged by the nature of your incense blend. Poetry was another of the same kind of art. A man wouldn’t even see a woman’s face — maybe he’d just glimpse the hem of a woman’s dress and there’s something interesting about that. Or her fragrance is very particular and that catches his interest. He still hasn’t seen her, but he sends her a poem, and she sends a reply. You look at not only the sentiments in the poem, but also the handwriting. All of these express your self when you can’t show your face.

The women are always behind screens and fans. Was it usually the case that most of the men didn’t see the women’s faces at all?

Oh, yes. I had to think of ways of getting across that when Murasaki spoke to a man without a screen, how unusual that would have been. To speak to a man without a screen or a fan or a veil was more shocking than a casual sexual encounter, which would have been more common.

It’s remarkable that people who almost never saw each other’s faces could have so many of these dreamlike sexual encounters. Was it really that common?

Yes. Mostly they happened at night so faces were glimpsed very dimly. A man wouldn’t necessarily see a woman’s face until he was in her bedroom. In one of the Genji stories he senses a promising creature off in some house and when he finally gets behind her screen, she has a long red nose and a high bulging forehead.

Lady Murasaki’s story is in some ways one of disillusionment. The court didn’t live up to her vision of it once she finally got there.

One of the main themes of the book is that there’s nothing worse than getting what you think you want and it’s not what you imagined. There are passages in her diary where she’s clearly very depressed. What came to me was the idea that when she was young and first writing about Genji, she had this very idealized vision of courtly life. Then she gets there and there’s all this backbiting. I think she felt very much an outsider. She was disillusioned. The political leader of the country had his own ideas about how he wanted to use her work, while she was going in another direction. This is all my conjecture but it’s based on her statements in the diary, and also the end of the “Tale of Genji” is written in a very different vein. It’s much darker than the earlier parts. Modern readers find it a lot more interesting. It’s very interior and her characters have a very modern sort of angst. I imagined that her readers weren’t so thrilled with that, and while I don’t know this, I guessed that that might be one way of explaining why she was so depressed.

You don’t depict romance as a tremendously important part of her life.

She certainly wrote about it a lot in “The Tale of Genji.” We don’t know much. She married late, and she resisted it, but then she seems to have been happy, judging from some of the poems in that later period. Clearly she had to have experienced love affairs — she knew so much about relationships between the sexes. So I felt I had to make one up, the riskiest part of the book, which is her affair with a Chinese man when her father was stationed in a place that was a lot like the Wild West.

She says that the thing that really bothers a woman in a man is unfaithfulness, while the thing that really bothers a man in a woman is jealousy.

That’s a theme throughout the “Tale of Genji.” In a way you could say it’s a pretty universal theme. As Murasaki writes about him, the shining Prince Genji is faithful to all of his women. He really is. He loves them all. He’s equally sincere to all of them. But the main character of the book, whose name is Murasaki, becomes tormented near the end of her life, afraid that she will lose her beauty and therefore Genji’s interest. You see her really suffer.

One of the most things that most intrigues Western readers is the Japanese practice of blackening a woman’s teeth.

You can read through the whole 600 or 700 pages of “The Tale of Genji” and not realize that all these beautiful women Genji had these affairs with had black teeth. They continued this up until the end of the 19th century, which we often forget. Murasaki didn’t need to write about that because everybody knew it. I felt that to make that convincing I had to find a way to believe that black teeth were beautiful and so I painted my teeth black and went around for a while trying to imagine how that would have worked. I even do that now for some of my book signings.

My husband was very against the idea. He thought it was too much of a gimmick. But afterwards, he said “While you were talking it didn’t scream ‘black teeth!’ but it did create a shadow that removed the distraction of white teeth. And it emphasized your hair and cheekbones and it made you look very beautiful.” They powdered their faces white, and against that pale face teeth would look yellow. They also shaved their eyebrows and painted large round ones halfway up their foreheads, which also changes the proportion of the face. Every culture does something for the sake of beauty that other cultures think is very strange.

Do you find any similarities between Murasaki and the other aspect of Japanese society you’ve studied, in your case first-hand, the geisha?

Historically, Murasaki lived 500 years before the first geisha, so they don’t have anything to do with each other. I think that Murasaki herself would have been a terrible geisha, just in terms of her personality. She was so introspective, a very interior kind of person, whereas a geisha has to be very gregarious and outgoing.