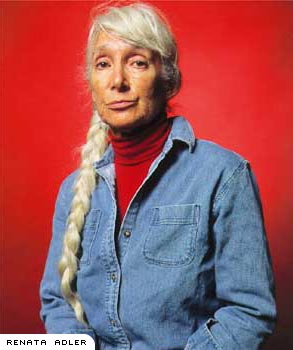

In an episode reminiscent of Mary McCarthy’s famous, hell-raising put-down of Lillian Hellman — “Every word she writes is a lie, including ‘and’ and ‘the.'” — a single sentence recently caused a furor in the New York literary scene.

Renata Adler had already been under heavy fire for weeks before anyone even noticed her statement, in her book “Gone: The Last Days of the New Yorker,” that she’d once declined to review the autobiography of Watergate icon Judge John Sirica because he was “a corrupt, incompetent, and dishonest figure, with a close connection to Senator Joseph McCarthy and clear ties to organized crime.”

The discovery revivified the controversy kicked up by the book, which is an angry cri de coeur arguing that the fabled magazine had passed from a literary showcase to a trendy slick with fashion coverage and celebrity profiles. “Gone” got generally favorable reviews in the rest of the country, but reviews in New York — many of them written by people associated with the New Yorker, such as one by former editor Bob Gottlieb — were generally scathing.

None of them, however, mentioned the Sirica comment. It wasn’t until a month later that Sirica’s son, Jack, a reporter for Newsday, called it to everyone’s attention by faxing a letter to Adler’s publisher, Simon & Schuster — and distributing copies to the press — that demanded Adler provide either a retraction or “any evidence whatsoever.”

It was a demand that the New York Times soon endorsed in an editorial, two days after a piece by Times reporter Felicity Barringer recounted a stormy interview with Adler. Barringer asked Adler to provide support for the statement about Sirica, and Adler declined to do so, saying she intended to write her own account of the matter at a later date. Barringer wrote that when she’d asked Adler, “Why wait months to publish your evidence?” Adler had called the question “deeply silly.” Adler calls the Times’ coverage of her book “institutional carpet bombing” — negative articles about her in nearly every section of the paper, including Arts, the Sunday Book Review and Sunday Magazine, Business/Financial and the Week in Review. Adler also noted that Barringer asked Bob Woodward to comment on the Sirica charge, even though Adler had famously trashed his volume “The Brethren” on the front page of the Times Sunday Book review; and that the Times’ strongly worded editorial page indictment of Adler’s ethics was written by Eleanor Randolph, whom Adler had cited for some inaccurate reporting in “Gone.”

Adler wrote a letter to the editor protesting that she was being ganged up on (“The Times has now attacked my ‘irritable little book’ no fewer than six times — in its Sunday and daily papers, its Letters column, its Arts, Media, Editorial and Business sections. The prose has been colorful: ‘off-hand evisceration of various literati,’ ‘drive-by assault,’ ‘Iago,’ ‘irresponsible,’ ‘despicable,’ and so forth. I wonder what the Sports section will say”), that conflicts of interest were being ignored and that Barringer had misquoted her.

However, Times executive editor Joe Lelyveld refused to run it, telling Adler he had decided it was time to “give the matter a rest.” Two days later, the Times ran an item on the clash in the Sunday edition’s Week in Review.

Adler was once a star writer for the Times herself, and wrote on and off for the New Yorker starting in 1963. She wrote speeches for the Nixon impeachment inquiry of the House Judiciary Committee, and as a reporter she covered Selma and the Six Day War, and was one of the first female journalists in Vietnam. But she has felt a collegial chill for her blunt opinions before — her previous most famous single sentence was one in which she said film reviews by her New Yorker colleague Pauline Kael were “piece by piece, line by line, and without interruption, worthless,” because Kael was harsh on independent filmmakers. And in her book, “Reckless Disregard,” Adler rather conclusively showed that esteemed news organizations CBS and Time magazine had been somewhat less than fair — or honest — in stories about Gen. William Westmoreland and Ariel Sharon, respectively.

Still, that book got rave reviews — including one in the Times — as did Adler’s three previous books. (Michiko Kakutani called her novel “Pitch Dark” a work of “magic.”) Just last year, she won a Washington Monthly Journalism Award for her blistering critique of the Starr Report, which appeared in Vanity Fair.

In the current issue of Harper’s magazine, Adler defends the Sirica comment and discusses the Times coverage of it. But the roots of the current controversy — and Adler’s feud with the Times — seem to go back further than that.

In a lengthy interview, she discussed her embattled year so far, and proved herself to be as unfiltered in real life as in her writing.

Let’s start at the beginning: What made you decide to write “Gone”?

Well … it was time, it was time. What happened at the New Yorker seemed such a waste. There were things that could have been done. There weren’t many people who were placed to do them, but for example, if you take Bob Gottlieb — Tina Brown, I mean Tina Brown is Tina Brown, but Bob Gottlieb, there was something else he could have done. But he was too busy talking about how loved he was. So, I thought that was it. I mean, it wasn’t something in a day, but it was a loss.

A loss you document, at least partly, by portraying the changing character of staffers there, including some absolutely devastating characterizations — in particular, you unload on Adam Gopnik.

I do. People characterized that as “cruel,” and that surprises me. Because if you look at it, physically, it’s not cruel. I mean, there’s no deformity.

What about describing him as “meaching”?

Well, he was meaching!

Fabulous word, but it conveys such a Dickensian image of stoop-shouldered sniveling and hand-wringing.

Well, I thought, this is the distillation of the genuine article. I mean, I really intended it as I wrote it, think of it as an understatement and would write it again. I guess with the Pauline Kael piece, I said what I think and do: It isn’t fair to attack somebody weak, or some poet in a garret. You go for the bullies. I think I did that here.

Such characterizations constituted an attack on a very well connected elite. You must have known trouble would ensue.

I guess so, but I really underestimated it terrifically. Because one thing that was clear was it wasn’t going to be an enormous bestseller. I thought there’d be sort of a “Who cares that much?”

Every single person in New York, apparently. You even got bad reviews from some old friends — such as John Leonard, who once said, “Nobody writes better prose than Renata Adler.”

John Leonard knew what he had to do and he did it. And I wouldn’t expect anything else.

In a New York magazine profile, Michael Wolff actually draws on your personal friendship.

But it was friendly, so I was really grateful for it. You know, Joan Didion once said about reviews of her books: If they’re unfavorable, you always think, well, thank God they didn’t find the part that’s really terrible.

What did you think about the piece in the New York Observer by Bob Gottlieb, whom, once upon a time, you recommended for the top job at the New Yorker?

I can’t remember much about it except that he said he was cast as a bad guy or something. And I thought, I didn’t cast him as a bad guy, I cast him as an idiot — which I think he abundantly was.

He says the “book is riddled with errors, of varying degrees of importance and disingenuousness,” and backs it up with some facts you did indeed get wrong — several names, and the date of Richard Nixon’s resignation.

Well, here’s the thing: All factual errors, including typos, are lamentable and there’s no excuse for them and I feel bad about them. On the other hand, these errors cannot be disingenuous. What’s he talking about — I misspelled people’s names for disingenuous reasons? I mean, Nixon resigned the year he resigned and I knew it perfectly well — I was on the impeachment inquiry. This stuff is inexcusable but it’s absent-minded.

However, it bolsters an opinion that you just rushed something off the top of your head.

Well, that’s fair. It’s inaccurate, but it’s fair.

And some of his accusations are more substantive: He says you are “seriously wrong” when you claim the New Yorker didn’t really begin to lose money until his tenure.

He’s wrong. I mean, why does he think Si Newhouse fired him?

Gottlieb was one of the first to shift discussion to a psychological analysis of you as someone caught up in a “dysfunctional family.” Your response to such discussion?

It’s just clichi and it’s so stupid — about a magazine! That I was competing for Mr. Shawn’s attention against Jonathan Schell — I mean, it’s so nuts! First of all it’s not true — it’s so patently untrue, because it means you can never discuss an issue. This is one of those analysands, I’m afraid, who say, “Well, we have here a classic.” But whatever they look at they have here a classic, so there are no issues, there are no real personalities. I mean it’s a catty piece but it’s just so dumb. It’s just a retribution piece.

Arthur Lubow’s profile in the Sunday Times Magazine relied heavily on Freudian analysis, too, portraying you as a woman — a notably single woman — possibly deranged by deep-seated issues with men based on some father fixation. For example, he says you obtained degrees from Bryn Mawr, Harvard, Yale and the Sorbonne as a way of “treading water as she waited, like most women of her generation, to marry.” Is that something you told him?

No! But the Freudian stuff — and the wool — whatever business he said my father was in — I mean, it just wasn’t right.

Your father didn’t run a wool factory in Danbury, Conn., as Lubow says in the article?

No, he never had anything to do with wool in his life.

The family money doesn’t come from wool factories in Germany?

No. There is no wool in our family at all.

Where did he get all that?

Beats me.

Well, how about when he says, “Shawn first appeared to Adler to be the father she had never had (warm, supportive, accessible) and then proved to be quite like the father she did have (remote, self-involved, unreliable)”? Is that how you would describe your father?

No, not at all. Nor is it how I would describe Mr. Shawn. It’s just dime-store analysis, and it’s wrong.

OK, a month later, new stories about you — especially at the Times — began to focus on something more clear-cut: the Sirica comment. I want to ask you about the now-famous interview with Felicity Barringer, because that’s where most people first read about this, and almost every piece the Times has run since refers to comments you make in it. First, how did Barringer approach you?

She said, “I’m writing a piece about ethics in book publishing — these people who slap something between two covers –” she actually said that “when I have to justify to my editor what I’m going to print. What are your sources?” It was rude, it was bellicose, it was …

She was rude and bellicose?

Oh, very. There wasn’t a moment’s pretense. It was “Don’t give me anything about this, and don’t give me anything of that.” Very bad detective in the good-bad detective thing. And the fact is that, unless you think, Oh … my … God, this is the New York Times!, it’s a totally ineffective way to report. I thought, Wait a minute — “slapping between two covers,” and “Don’t give me any of this”? Well, it doesn’t take a radar …

What about your “deeply silly” comment? I gather it had to do with being asked to give up your source —

Through her! To a newspaper that is on the record as saying they never give up sources. But she also said, “When and in what publication will it appear?” The reason that’s a deeply silly question, unless you’re working at the New York Times, is you have no guarantee from anybody of when and where it’s going to appear. She said, “So is it going to be in [mocking tone] Vanity Fair?”

But when you wrote that sentence about Judge Sirica originally, didn’t it occur to you that without a little more backing it was inflammatory?

Well, the truth is, if I had it to do again, I would amplify, but only by another sentence or two.

So do you regret now that it wasn’t amplified?

No, I don’t know if it would have mattered at all. I mean, the Times ran four pieces about me even before Sirica. I don’t think I did an injustice, I don’t think it was wrong to leave it that way — I was not doing a reporting piece, I was writing a memoir of what happened at the New Yorker.

Still, you must have expected a backlash.

I guess I really did think other reporters knew about it. I mean, there was all the criticism of Sirica from lawyers, including very conservative professors of law, at the time.

Your critics are questioning your evidence of Sirica’s criminal connections. The Times focused on your contention that the police were paid off to protect the bootlegging operation of Judge Sirica’s father, Fred. As the Times’ Alex Kuczynski put it, you state this “without citing a direct source.”

But I did! I did cite a direct source — right at the beginning of the paragraph in which I say that.

The testimony you cite from William R. Emmons, the son of Fred Sirica’s partner?

Exactly.

Which is what, precisely?

Letters.

Letters to you?

No.

Then to whom?

That, I’d rather not say.

Why not?

My source asked me not to if I don’t have to. I’m allowed to protect sources, too. I mean, Bob Woodward would have said, “I talked to Deep Throat and he says it isn’t so.” What I have is written evidence, and it sure beats Deep Throat.

Well, what else is in them?

That his father shared equally with Judge Sirica’s father, that Judge Sirica’s father himself distributed liquor to customers — there’s stuff about how he talked them into it, what the connections were — there’s more.

You also show that Sirica broke the law by being involved with boxing in Washington, where it was illegal, which is why he did it under an assumed name. Inside.com — which is run by another former New Yorker staffer, Kurt Andersen — called this “remarkably thin stuff.” They cite boxing historian Bert Sugar, who said only fighters at the very top were corrupt. They also quote Felicity Barringer as saying of your evidence, “I guess that means Joe Louis had ties to organized crime.”

That’s a preposterous misrepresentation. Joe Louis, so far as I know, never promoted fights where they were illegal, never fought under pseudonyms where it was illegal to fight under pseudonyms and was not breaking the law while he was also an attorney. He was never described as a hero in the political life of his country, he was never a judge of the court, he was never a U.S. attorney responsible for prosecutions under the Volstead Act when he was living in his father’s house when his father was running a bootlegging operation. You know, I didn’t want to attack Sirica’s whole life, nor do I want to spend my whole life attacking Judge Sirica. I just wanted to say my sentence about him was sound. I don’t think there’s any question that there is a mass of substantive, public, written evidence to back that sentence.

Yet before your Harper’s article even hit the newsstands, the Times had run Kuczynski’s article, and one by Martin Arnold saying there was no proof in it at all.

Martin Arnold’s piece is an egregious example of absolute disinformation. You can’t say there’s nothing there. I mean, you’ve got to address it.

Arnold also uses “Gone” as evidence that publishers don’t fact-check books.

I mean, the New York Times, talking about fact-checking — there are no fact-checkers for the daily news! None! So for Martin Arnold to say you can’t rely on my book as you can your favorite newspaper — by which he meant, of course, the Times — that’s just total, absolute nonsense.

So, here’s your chance to set the record straight — was “Gone” fact-checked?

Oh, of course there was checking! It’s much more careful at Simon & Schuster than at the New York Times. I’ve worked for both so I know.

Judging from your account it seems there has been a personal edge to this thing between you and the Times since the beginning. Any idea why? Does it have to do with your press criticism in “Reckless Disregard”?

Even leaving aside “Reckless Disregard,” you’re just not allowed to criticize the press. I mean, what are they so angry about really? If they were really so interested in my claims about Judge Sirica, they’d look into it themselves, instead of telling me to go do it for them.

Why don’t they, do you think?

“Lazy” is such a key word in this stuff. Being on the phone is what they call legwork now — you know, somebody who has an agenda calls you and demands your sources. It’s very strange. But it’s a bureaucracy at the Times, where nobody has jurisdiction, as though they were all independent fiefdoms. They’re just an organ of a certain kind of dogma where they praise each other. It’s like a Vichy newspaper, trying to ingratiate itself. Except there’s no Vichy government. So they’re the government as well — it’s not just Pravda, it’s the Kremlin. It’s scary when you take a book that’s not been overpraised, Lord knows, it’s not a source of information for what they claim to be interested in, and to write 10 pieces, well — who’s the David here and who’s the Goliath?

And the other publications that have been critical — they’re just following the Times’ lead?

Well, it’s interesting that since Dinitia Smith’s piece, the first piece in the Times about “Gone,” they all quote from each other that I left the New Yorker in 1989. I don’t know where they got that date. I never left the New Yorker.

What do you mean?

Nothing happened in 1989.

You never quit the New Yorker?

No, I still get the staff list and I’m on it, for what it’s worth.