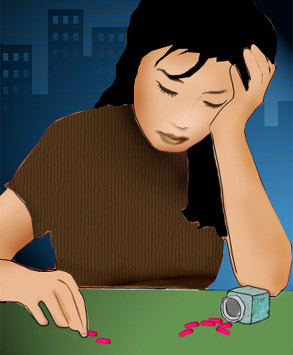

My patient wants to kill herself.

She carries a knife in her backpack. She plans to plunge it into her heart. “And I could do it,” she tells me quietly, with a confidence that makes me shift in my chair. She’s in chronic pain, has been since the accident to her leg six months ago, but now, she says, it has broken through, so piercing she can’t focus, can’t think of anything but death. My job is to keep her alive while my colleague, a pain specialist and friend, works to find something effective. “There’s too much left to try,” he has told me.

She’s 34. Before the accident she was a prominent attorney, fiercely bright, racing toward partnership with the single-mindedness of a Navy cutter. Meeting her today, you’d think she was a soccer mom, auburn hair framing high cheekbones, a golf shirt with a tiny jelly stain from one of her kids’ sandwiches on her sleeve. She has that familiar, weary attractiveness, like so many of the women in my age group.

I want to hospitalize her. “Yes,” she tells me, sounding like a lawyer, “you can make me do the 48 hours in-house, but as soon as it’s up I’ll tell them I feel better, the whole thing seems like a dream now. And once I’m out I’ll do what I planned.”

“And,” she says softly, lowering her eyes, “if you hospitalize me against my will I won’t work with you again.”

This isn’t one of those cries for help I’ve come across before: shallow cuts on the inside of an arm or taking a few too many pills. I know she’s serious. She has been rehearsing — driving to an isolated spot with the knife in her backpack, drinking heavily and holding the knife over her chest.

When I was finishing my training at McLean Hospital, a psychiatric hospital affiliated with Harvard, a girl on one of the open-door units hanged herself from a fire escape. She was in one of my groups. She’d gathered her bedsheets and quietly walked outside. They found her a few hours later. She was only 17. And now, sitting here in my office, I can see her face, her eyes and the gentle slope of her cheek, as if she’d just left.

“Could you page me if you’re about to do it?” I ask.

She won’t answer.

Our session did not start gently with talk about weather, parking or the slowness of the elevator. She followed me from the waiting room to my office, sat down, dropped her backpack and muttered, “What is there to say?” It has been like this lately. She starts with “Why am I here?” or “You can’t really help me.” And her hopelessness fills my office like a cloud of suffocating ink.

She knows my history. That my training as a psychologist was interrupted by cancer. That I’ve had a bone marrow transplant. That I’m familiar with pain and the hopelessness of a horrible prognosis. I’ve been writing a book that has gotten some publicity, and some of my patients have heard about it. One afternoon she came in and said, “So, you’re a writer.” I swallowed hard. Therapy, after all, is about the client. It’s not supposed to be about me. She asked about the strange title, “Mom’s Marijuana,” and I explained as best I could about my illness and about my anti-drug mother growing marijuana in the backyard to help me. I tried to redirect her, but like a cross-examining attorney, she peppered me with questions. Eventually, she knew the skeleton of my story.

Initially, it helped. My history legitimized me. She listened when I told her she was more capable than she thought of tolerating the harsh side effects of her medications. But now she resents it. She has lamented, “I must seem terrible to you; you fought so hard to live, and here I fight to die.” And she has been right.

I’ve struggled with how to help her find a hope that I never really lost. Even when I was certain that I was going to die, even when it was confirmed by physicians, at least an ember of hope burned. Until now, I’ve believed that, with grit and hope, we can endure most things. It has been true for my patients, though not for her. For the first time in my career, I can’t understand a patient. And so I’ve withdrawn to the safety of psychological theory and science.

I’ve tried cognitive-behavioral and dynamic approaches. Existentialist. Humanist. Interpersonal. I’ve referred her to a psychiatrist, who has put her on antidepressant after antidepressant. I’ve consulted my old mentor. But her mood has continued to march downhill. And the bottom is coming up to greet us, fast and dark. I feel a frantic urgency rising in my chest.

Now she calls me judgmental because as I talk I wag a finger. I invoke her children: Have you taped photos of them to the knife? No. Could you assure versions of yourself 10 and 20 and 30 years older that you’re doing the right thing? No. And then, in the quiet between us, I feel as if I’m trying to sell her a car she doesn’t want.

She counters, “You’ve no right to judge. You can’t feel my pain, my losses.” She’s right and her truth stings. “You’re disgusted with me.” No, I want to say, but I am disgusted, and tired. “You affect me,” I tell her. “Powerfully. I’ll be devastated if you kill yourself. So don’t do it.” And inside I’m trembling for her and those children. And maybe myself, too.

I know I’m not supposed to let her see my disgust, my frustration, my anger, but they have seeped out. I find that in this foxhole of intensive care psychiatry, I do things I don’t do elsewhere. I share what I feel for her, even when I don’t want to — especially when I don’t want to.

Before she leaves she gathers her backpack and sighs. She stands up, thanks me for not hospitalizing her and whispers a promise. She’ll page me if she’s about to kill herself. She opens my door, then turns back toward me, curiosity in her face. “What will you say if I do page you?”

“Don’t worry about that now,” I tell her. But as the door closes I wonder too.

Twelve hours later, I am suddenly awakened. “What’s happening?” I wonder. Oh. I’m in bed. It’s still night. What’s that sound? Then I see the familiar outline of my pager and the little light flashing on the screen. My heart is pounding. The clock says 2:17 a.m.

I get up and carry the pager into my study, where there’s a cellphone and our house phone. I can call the police on one while talking with a patient on the other. I dial and the paging operator tells me to hold on. It’s bright outside. There must be a full moon. I can see deep into the desert.

Then I hear her voice. “Sorry to wake you up,” she says, “but I promised.” Her voice is unmistakable. Monotone. It has been that way for months. When I first started working with her I phoned to confirm our appointment time and heard her answering machine, taped before her accident. She sounded strong, giggling a little, with the sound of children and a yapping dog in the background. But in our first session, she spoke slowly, her words like plodding little soldiers.

“Where are you?” I ask. It’s my first job to find out where she is so I can send someone there. I turn on my cellphone. 911?

“Not so fast — let’s talk first.” Then I can hear it. Her enunciation is off. She said, “Lez talk first,” as if her brain is sending signals and her lips can’t keep up. I search my mind for the substances she has on hand. Painkillers, tricyclic antidepressants and, probably, alcohol. A lethal combination.

“What have you taken?” I ask.

“Nothing too serious,” she says. “Some vodka. But it gave me a headache, so I took a few Tylenols, just four, I promise.”

There’s silence on the line. “What are you going to do?” I ask.

“Haven’t decided,” she answers. We sound so businesslike, you’d think we were contemplating a shopping decision.

Silence again. “I think I’m going to do it this time,” she says softly.

“You paged me to say goodbye?” I ask, an edge rising in my voice.

“I paged you because I promised.” The hair on my arms stands up. I start to dial on the cellphone and then realize she hasn’t told me where she is.

And at this moment, I don’t know what I’m doing. I’ve read accounts of psychologists and psychiatrists talking people out of killing themselves in the middle of the night. The professionals always sound brilliant, eloquent. Every argument for living is so surprising and persuasive. But right now, those accounts seem merely fantastic. I’m just an overeducated man with a cellphone.

“It’s lonely, isn’t it? Out there,” I offer. My primitive attempt at empathy falls flat. “Look, um. If you’re about to die, then I’m getting off the phone. I’m not interested in being your witness.”

“I don’t want you to witness it,” she says. There’s a long pause. “This is euthanasia,” she tells me.

“Bullshit.” My anger spills out. “You don’t know that we won’t be able to find something to help with the pain. It’s selfish. You killing yourself would devastate me and your husband and your children.”

I hear a quick, controlled exhale. Is she crying? I decide that she is.

“I was pretty set on it tonight. I’ve been in a great mood all afternoon, just knowing I was going to do it tonight. It’s the first time I’ve been happy in months. Shit.”

“You can always kill yourself tomorrow if you still want to,” I offer. Then I hear a quick snort and a tired laugh, and then I’m laughing too.

“That’s ridiculous,” she says, still laughing. Then she’s suddenly serious. “You’re stalling. You’ve been stalling.” She catches me still laughing. I have to switch gears quickly and I feel tenuous, as if the cliff beneath me is starting to crumble.

“You’re right,” I admit, “I’ve been stalling. And now I’m going to get off the phone and you’re going to be alone. And you get to choose. There’s nothing I or anyone else can do to stop you from killing yourself. I’m not going to send the police out looking for you or call your husband or anyone else. I know there’s a part of you that wants to die tonight. I know that death sounds like a relief to that part of you. And I’m guessing there’s another part of you that wants desperately to live. And tomorrow, if you’re still alive, I’ll be in my office waiting for that part to show up.”

When she came in the next day I wondered if she’d been kept alive by the soothing smell of the desert, of jasmine and creosote. Or maybe it was a snapshot memory of her husband and children. Or maybe it was that someone else who’d also suffered thought she could survive. Or maybe it was something I said.

A few weeks later, when the crisis had passed, she wanted to talk about it. “You know,” she started, “you were a major pain in the ass that night. And you didn’t say a damned thing that was useful.” Then her voice changed. “But you were so scared and pissed off — like you really cared.”

“I don’t really,” I said. She looked startled.

And then we were laughing.