During the days following Bob Knight’s ouster as basketball coach at Indiana University, a star was born. Caught in the media maelstrom, there he was, on FoxSports Net, CNN, ESPN, even penning an account on Salon.com. Murray Sperber had won, you see, and he seemed to be enjoying it, too.

As Knight’s foremost (and often lone) critic, Sperber, an English and American studies professor at I.U. for 29 years until a spate of threats from pro-Knight yahoos sent him on a forced sabbatical earlier this year, has come to embody the crusade to eliminate big-time college sports. After the sacking of Knight, Sperber has been hailed as the victor in a modern-day clash between the academy and the locker room, and he’s hoping to parlay the hype into a momentum that may radically alter college athletics. Ironically, it may not be for the better; while Sperber’s intent is to save the integrity of academics, his agenda recalls a time when university life was the sequestered province of a privileged white elite.

In a sign of just how much higher education has changed in this century, there was no genteel elite to be found when a pack of enraged students marched on I.U. president Myles Brand’s residence in the aftermath of Knight’s firing — burning the president in effigy while chanting, “We want beer!” Watching what he called “the riots” from his exile in Montreal, Sperber saw the best type of commercial for his just-released book, “Beer and Circus: How Big-Time College Sports Is Crippling Undergraduate Education.” He was witnessing, in his view, nothing less than his thesis come startlingly to life.

“On one level, it was gratifying to have an intellectual theory and then to get caught up in events that bear out that theory,” Sperber says. “But it was also disturbing. Those images — that was pure ‘beer and circus.’ Don’t think for a minute that those students weren’t drinking.”

In short, Sperber’s argument is that big-time collegiate sports subverts undergraduate education because large universities that emphasize research and graduate programs, in an effort to field winning teams, will spend inordinate sums of money on bloated athletic departments rather than on providing quality undergraduate education. Such schools, he asserts, use sports to keep their students happy and drunkenly distracted — the educational mission of the university be damned.

Sperber paints a not-too-pretty picture of the state of education: Close to 40 percent of undergrads never take English or American lit; 58 percent never take a foreign language; almost a third successfully avoid ever taking a math course. Sperber posits that this is how the administrations of America’s universities would have it, that they’ve created the conditions that led one student to tell Sperber his college education was “a four-year party — one long tailgater — with an $18,000 cover charge.” This is what “beer and circus” has wrought, Sperber maintains: Binge drinking, cheating in class, huge lecture halls taught by teaching assistants and a faculty that has signed onto a tacit “nonaggression pact” with students so as not to interrupt the ongoing party with football or basketball games at its epicenter.

If Sperber has his way, all this will change. And, thanks to his increasingly high profile courtesy of the Knight imbroglio, he very well might lead the charge. Sperber has helped form the Drake Group, a consortium of academics intent on ending athletic department hegemony on the university campus. (Sperber is joined by, among others, Smith College’s Andrew Zimbalist, author of “Unpaid Professionals: Commercialism and Conflict in Big-Time College Sports,” and the University of New Haven’s Allen L. Sack, coauthor of “Athletes for Hire.”)

They are a self-described radical group that favors a return to the low-key style of intercollegiate competition now practiced in the Ivy League and at Division III schools like Emory University in Atlanta and Hamilton College in central New York state (two of Sperber’s pet models) where, instead of athletic scholarships, a system of need-based financial aid — as for any student — is in place. Their mantra is “no tinkering” and they would release to the public the academic records — classes taken, but not grades — of athletes, so as to weed out those who skate through school taking “Mickey Mouse” courses.

The prescription may seem radical, but it also contains an element of conventionality, for it panders to an academic mind-set still blinded by “dumb jock” stereotypes. Sperber’s handwringing often morphs into fuddy-duddiness, as when he dismisses students who paint themselves in team colors and play to the TV cameras: “Not only might the parents of these students question the ‘money’s worth’ of their tuition payments, but many other Americans … might wonder whether undergraduate life is merely fun and games, whether they should support higher education with their tax dollars.”

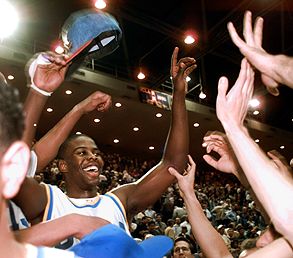

Absent from these fulminations is any sense of the integral role that “big-time” college football and basketball play in the undergraduate experience. What Sperber doesn’t get is that, for all its faults (Zimbalist’s book is particularly illuminating here, because of its focus on the economic inequalities endemic to a billion-dollar market where the laborers hardly get paid), big-time college sports is incredibly instructive on the issues of race and class.

I know this firsthand. I spent many a drunken night at the Syracuse Carrier Dome in the early to mid-’80s, cheering on the Orangemen — along with a similarly, uh, enthused audience that was easily the most multicultural gathering on campus. In the stands, blacks and whites hugged and high-fived, just as on the court. And it was there, on the basketball court and football field, that I saw meritocracy in action.

Because sport is such a measurable thing — you either score 20 points or you don’t — discrimination wasn’t a factor, a stark contrast with the world our classes were preparing us for. Moreover, these games linked the school to the surrounding community; the barriers between the privileged college classmen and “the townies” broke down, as evidenced on the call-in sports talk shows, where guys from factories argued with students over whether the coach ought to have called a timeout when he did.

Sperber would have had me experience none of this. Attending one of Sperber’s Drake Group powwows, Ken Shropshire, professor of legal studies at the University of Pennsylvania’s Wharton School (the only tenured, full-time African-American on a faculty of 200), sensed something was amiss. “I went because I’m in favor of reasonable reform, and everybody was well-meaning in that room, but there was a lack of searching for a route to preserve what’s good about the system we have now,” he says.

And what’s good about it is that it has produced people like Shropshire. Born and raised in South Central Los Angeles, Shropshire earned an athletic scholarship to Stanford University; through sports, he says, he learned the values that led him to excel in law school and now as an author and Ivy League professor. “I’m biased, but Stanford is an example of a school that has done it right,” says Shropshire. “They’ve proven that academics and high-profile sports programs needn’t be mutually exclusive.”

In U.S. News and World Report’s annual ranking of universities, almost half of the top 50 schools (albeit in a notoriously contested selection) have high-profile football or basketball teams, though in his thesis Sperber dismisses all but the rare exceptions, the Stanfords and Dukes. By choosing instead to trumpet the Ivys and Division III schools like Emory and Hamilton, Sperber runs the risk of undermining advances he has elsewhere championed.

In “Onward to Victory,” his book about Notre Dame football, Sperber illustrates how, in the 1940s and 1950s, it was through football that blacks first began to integrate the academy. (“I do skirt the issue of race in this book, largely because I dealt with it in ‘Onward to Victory,'” Sperber says, while conceding that, “unfortunately, [the agenda of the Drake Group] brings up a lot of race issues.”)

“I’m suspicious that what’s behind the academic call for doing away with athletic scholarships is a nostalgia for the good old days, which leaves out everyone but white Anglo-Saxon Protestants,” says Scott MacDonald, who teaches film studies at Bard College and who has taught at Division III Hamilton, where only 3 percent of the student body is African-American. MacDonald got his doctorate from the University of Florida in the ’60s, where the big football game — the Gators vs. Georgia — was and still is billed as the “world’s biggest cocktail party.”

Then, as now, the party was about much more than the game; it was about kids away from home for the first time, testing their limits and themselves, which might be, after all, the literal definition of education. “What’s wrong with the Dionysian tradition of letting out what’s normally repressed?” MacDonald asks. “College is about this kind of explosion. It should be a place where special excitements and possibilities are part of the package. I’m pretty sure drinking to excess predated our collegiate football leagues by, like, thousands of years.”

Indeed, Sperber’s concerns about binge drinking, cheating and undergraduate teaching done by teaching assistants seem spuriously linked to sports. As MacDonald attests, there is no dearth of drinking and barfing on the campuses he’s spent a lifetime teaching at, none of which features high-profile Division I teams.

Add Sperber, then, to the list of otherwise seminal thinkers who have overlooked the progressiveness of sports, who fail to see that the sports subculture is often ahead of the culture at large when it comes to hot-button social issues, whether it’s collegiate football’s role in integrating university life in the 1940s, Jackie Robinson kick-starting the civil rights movement seven years before Brown vs. Board of Education, Muhammad Ali spurring protest of the Vietnam War or that, today, at least on the playing field, the NCAA, NBA and NFL have achieved a level of colorblindness that the rest of the culture still aspires to.

Yes, add Sperber to the likes of the revered Noam Chomsky, who once said sports is a “way of building up irrational attitudes of submission to authority” and is part of “the indoctrination system,” or the normally cogent Katha Politt, who once wrote that “sports pervert education, draining dollars from academic programs and fostering anti-intellectualism.” When I think of them — brilliant minds, all — I am reminded of that uproarious scene in the film “Annie Hall,” when the character played by Woody Allen sneaks off to a bedroom to watch a Knicks game on TV during a New York cocktail party filled with famous intellectuals. When his disapproving wife comes in, Allen quips that he’s heard that Commentary and Dissent magazines are going to merge to form “Dysentery,” then returns his attention to the game. She angrily asks him why he’s drawn to “a bunch of pituitary cases running around in their underwear.”

“Because they understand the physical,” he replies. “These intellectuals are proof that you can be brilliant and have absolutely no idea what’s going on around you.” I’m with Woody, trying to focus on the game, maybe even cracking open a beer can, tuning out the stuffy chatter from the other room and wishing there was somebody in here to high-five with.