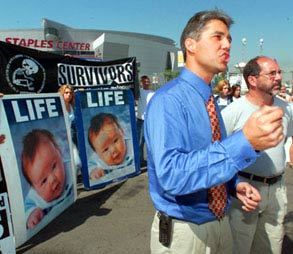

The Republican Party’s message hasn’t been lost on the Rev. Philip Benham, director of Operation Save America: “They love our vote, but they hate our voice,” he said. Benham heads Operation Save America, whose precursor, Operation Rescue, was sued into bankruptcy over its aggressive protest tactics.

His organization headquartered in Texas, and Benham is disappointed with Bush and the Republican Party for being “fuzzy on the edges” of the abortion debate. “I like W,” he said, “but he hasn’t taken a stand on this issue, and he never will.”

This should be a great time to be a pro-life crusader in the United States. A Gallup poll released in April showed 19 percent of Americans now favor outlawing abortion under all conditions, a 25-year high. The same survey showed that those identifying themselves as pro-life increased dramatically in the late ’90s. In 1995, self-described pro-choicers greatly outnumbered those on the pro-life side, 56 to 33 percent. In 2000, the poll marked a much slimmer pro-choice majority: just 49 percent to 42 percent.

On the big related issues — “partial birth” abortion and the approval of RU-486, the “abortion pill” — Gallup found 65 percent support for outlawing “partial birth” abortion, and also that 47 percent of Americans favored keeping RU-486 off the market in the United States, as opposed to 39 percent who wanted it to be made available. An ABC News poll taken Sept. 6-10 showed the same disapproval rate, with 45 percent supporting legalization of the drug.

The FDA ruled Sept. 28 to legalize RU-486. That decision had some anti-abortion activists up in arms. But in the first presidential debate, it only “disappointed” Bush, who claimed that he didn’t know what he could do to keep RU-486 off the market. “I don’t think a president can do that,” he said.

Wendy Wright, communications director for conservative group Concerned Women of America, didn’t find cause for concern in Bush’s response. “I wouldn’t necessarily expect the presidential candidates to know much about RU-486 so soon after the decision,” she said, adding that the Texas governor’s debate performance only reinforced her comfort with his pro-life credentials.

This attitude is typical of many in the mainstream pro-life community who have demanded little from the party that they helped put into office. They observed Bush’s dalliances with pro-choice vice-presidential nominees in silence.

That’s got hardcore anti-abortionists fuming. Nothing showed the pro-life split more dramatically than the schism between anti-abortion activists in New York. On the same chilly late September Saturday, the New York Right to Life Party and the New York chapter of the National Right to Life Committee held their annual meetings. But they didn’t meet together. The groups were separated by about 200 miles, and by a philosophical distance even greater. In the presidential race, the dissident Right to Life Party is backing Reform Party candidate Pat Buchanan, while the New York NRLC, like its parent group, is tacitly supporting Bush.

Guess which group’s candidate showed up to say hello?

True, the Buchananites were significantly smaller in number, with fewer than 100 people crammed into a damp, basement-level conference room of a Yonkers, N.Y., Holiday Inn. And when Buchanan did arrive, he devoted only part of his remarks to abortion, quickly slipping into the culture-war stump speech he premiered at Bob Jones University. Still, the faithful were not disheartened, and they cheered loudly when their candidate declared himself firmly in their camp and promised to appoint only pro-life justices to the Supreme Court.

Meanwhile, upstate at the NRLC event in Schenectady, N.Y., which drew 400 pro-life activists from around the state, anti-abortion leaders said that holding Bush to a litmus test pledge was unnecessary. This is politics, they said. He knows better. They understand.

“He’s already said that he’ll only appoint strict constructionists to the Supreme Court,” said Lori Hougens, communications chief for the New York State Right to Life Committee. “It would be so irresponsible for him to say any more.”

The Rev. Duane Motley, a featured speaker at the convention, wasn’t so delicate. “It would be political suicide for him to say there will be a litmus test,” Motley declared. “But there will be one once he wins.”

For a group based on moral absolutes, the New York chapter of the NRLC showed a surprising tolerance for the trade-offs of political gamesmanship. The Rev. Frank Pavone of Priests for Life argued that, while voting for pro-life candidates was something God required of good Catholics, Bush’s less-than-immaculate pro-life credentials were just fine. “We’ve got to stay away from the idea that a candidate has to be 100 percent pro-life, and that one who is 95 percent isn’t good enough,” Pavone said. “When I cast my vote, I’m not making a statement. I want to vote for someone who can realistically get elected.”

The priest wasn’t alone in this assessment. Other convention participants repeatedly referred to the pro-Buchanan pro-lifers as “naive.”

But the New York Right to Life Party isn’t a bunch of rubes, and they mixed their moral argument against Bush with a sophisticated electoral analysis, one that Buchanan echoed in his remarks. “The Republicans have written off New York. Bush has lost New York. He’s not going to spend a dime here,” Buchanan said. “If you support the Right to Life line here, that will send a message across America to those Republicans who are running away [from pro-life] to come running back as fast as they can.” In short, given that New York pro-lifers were going to vote for a loser anyway, why not vote for one who was 100 percent pro-life?

When answering this question, those affiliated with the supposedly politically savvy New York Right to Life Committee sounded naive. “The polls I’ve seen say it’s still neck and neck,” Motley insisted.

“I hope he hasn’t given up on New York. He can still win here,” Hougens said.

The latest Quinnpiac University survey shows Gore leading Bush 54 to 34 percent in the Empire State.

Even if New York is out of reach, Hougens claims, Buchanan’s candidacy is a threat to pro-life progress because it’s a threat to Bush elsewhere. “He’s not just running in New York,” she said.

As those on the left say a vote for Ralph Nader is a vote for Bush, so Republican Party pragmatists claim that a vote for Buchanan is a vote for Gore. But the pro-life idealists — like many Naderites — assert that depriving the party establishment of votes could teach them a valuable lesson and even lead to reform in the party.

Over and over, New York Right to Life Party chairman Kenneth Diem reminded those gathered that an immediate win wasn’t important enough to compromise on principle, and that a true victory for the pro-life side “will come in God’s time.” Benham, of Operation Save America, discounts the value of the election and claims that real pro-lifers should “stop throwing away our money” to elect Republicans. He expressed little enthusiasm for any candidate, except for a tepid good word for the Constitution Party candidate Howard Philips.

Bush himself has argued that he wants to change “hearts and minds” on the abortion issue before changing the law, but the Republican Party has hardly made the most of opportunities to do that.

At its convention this summer in Philadelphia, the GOP marched in step with its choice-tolerant nominee. Though conventions are usually a public reward for the party faithful, pro-lifers and other Christian conservatives got serious back-of-the-bus treatment throughout the event. No one at the love-in gave a speech devoted to abortion, but pro-choice Republicans were allowed plenty of stage time without the threat of party-sanctioned boos from the crowd. Jennifer Dunn, a pro-choice senator from Washington state, was the designated face of the new Republican woman during the Philadelphia show, and pro-choice Gen. Colin Powell was given a white-hot spotlight on opening night.

The latest congressional abortion battle, which few people know much about, is an effort to outlaw what pro-lifers call “born-alive” abortion. The procedure involves delivering seriously ill preterm fetuses and then withholding care until they die.

In the Illinois hospital where the practice was first publicly challenged, some mothers delivered fetuses at 23 weeks of gestation who were then given neonatal care. Other mothers who delivered just as far along into their pregnancies under similar circumstances were considered to have had abortions. The range of disabilities used to justify the procedure included non-fatal illnesses like Down syndrome and spina bifida.

The bill to outlaw the “born alive” abortions won easy approval in the House, and the debate surrounding the issue generated what in previous years had been considered a propaganda treasure trove for pro-lifers. Pro-choice advocates are on the record arguing that birth isn’t necessarily the dividing line between abortion and infanticide. The National Abortion Rights Action League calling the Born Alive Infants Protection Act “an anti-choice assault” that would “effectively grant legal personhood to a pre-viable fetus.” Furthermore, the president’s Office for Civil Rights wrote that protections against discrimination on the basis of age and disability don’t require doctors to treat seriously ill newborns as long as the parents consider them aborted.

This is far stronger stuff than the pro-life side was able to generate over the partial-birth abortion question, but Bush hasn’t mentioned it, and pro-life groups aren’t using the election to press the matter into the public consciousness.

If the New York National Right to Life leaders are any indication, mainstream pro-lifers are ready to back off on the partial-birth abortion question as well.

“I don’t know about moving on partial-birth abortion anymore this year,” Motley said. “We’ll wait until after the election and see what the Congress looks like.”

The low expectations of the right-to-life movement seem to reflect the GOP’s conviction that culture-war politics is a losing battle. But in the abortion debate, it looks like they might have raised the white flag too quickly.