Social gatherings can be a downer for Alan Leshner, the gruff, no-nonsense director of the National Institute on Drug Abuse, one of the two dozen separate agencies that compose the National Institutes of Health. As soon as he arrives, he says, other guests admonish him about how to do his job.

“I am probably the only NIH institute director who goes to a cocktail party and the first 12 people who come up to me tell me how to fix the drug problem,” Leshner said recently. “The director of the National Cancer Institute doesn’t have that problem.”

But Leshner, a key player in the Clinton administration’s controversial war on drugs who works closely with drug czar Barry McCaffrey, is not complaining. He has managed to survive, and even thrive, in his high-profile job since 1994 — not an unusually long tenure for an NIH director, but a lifetime for most politically sensitive public policy positions in Washington. Under his stewardship, NIDA’s budget, which is largely spent on research into substance abuse, has nearly doubled. And Leshner dismisses the notion that he is a shill for the administration’s anti-drug policies.

“We’re the science guys,” Leshner says. “Our job is to provide accurate scientific information. And since we understand that drug use basically is bad for you — from a public health perspective, not an ideology perspective — we think people shouldn’t engage in the behavior.”

But some critics have a less benign view of his role. They say he has supported research that bolsters the administration’s point of view, failed to fund projects that could undermine it, opposed research into medical marijuana and used images drawn from advanced medical technology to create misleading anti-drug campaigns.

“He’s the propaganda minister in the war on drugs,” says one sharp critic, Mark Kleiman, a University of California at Los Angeles public policy professor. He slips into a mock-German accent to deride Leshner’s claims of objectivity: “Of course, Dr. Leshner would say that all he cares about is the ‘zzzience.’ He’s convinced that if you can use ‘zzzience’ to show that drug abuse is a disease, you’ll get people to stop hating drug addicts. But that approach doesn’t work. All he does is reinforce that these drugs are bad and therefore we should be more repressive.”

Because of the emotional nature of the issue, Leshner is used to being a lightning rod for criticism from those, like Kleiman, who challenge both his priorities and his methods. A psychologist who previously served as acting director of the National Institute on Mental Health, Leshner, 56, makes no apologies for his tough-guy swagger, which he says he honed while spending summers at his grandparents’ borscht-belt hotel. He gleefully describes himself as “obnoxious,” acknowledges that he is “hated” and spells out his mission with no apparent doubts about the purity of his motives.

“I’m not the NIH director responsible for bungee jumping,” he says. “I’m in charge of speaking with people about the risks associated with drug abuse. It’s your business if you want to smoke marijuana. I just present you with the data.”

In helping to sell public health messages to young people, Leshner himself acknowledges, he’s swimming against a backwash of skepticism about government anti-drug messages that’s only been heightened by the vapid “just say no” campaigns of the past. “This is a constant uphill battle,” Leshner says. “A lot of people are going to assume that everything we put out is hyperbolic.”

NIDA spends most of its $780 million budget on research about drug abuse, with programs focusing on treatment, prevention, epidemiology and the biology of addiction. Few critics complain about that peer-reviewed process, although some believe Leshner should be pushing NIDA to fund investigations of alternative drug policies, such as decriminalization in other countries.

Leshner runs into controversy because his institute’s public health role is intimately tied to the campaigns of McCaffrey. NIDA and McCaffrey’s White House drug office are independent entities, but McCaffrey is the public mouthpiece for the research that NIDA generates. Far more than previous NIDA directors, Leshner strives to incorporate the results of NIDA-funded research into effective public messages for anti-drug efforts.

The Tweedledum-Tweedledee approach appears to please both directors, who have formed something of a mutual admiration society. McCaffrey calls Leshner a genius. Leshner praises McCaffrey’s “visionary leadership” in blending health and criminal justice approaches. “He genuinely understands, respects and supports scientific approaches to the drug issue,” Leshner says. Others would counter that while McCaffrey has supported some new approaches to treating drug abuse, that work has been overshadowed by his support for the traditional get-tough approach in America’s cities and the coca fields of South America.

Leshner’s involvement in the war on drugs is intended to humanize it, and, in fact, his approach to the issue of medical marijuana and needle exchange for heroin addicts and other injection-drug users, has been more nuanced than the braying from the drug czar’s office. But some critics claim that instead of NIDA’s initiatives elevating the image of the war on drugs, Leshner’s association with McCaffrey has had the inverse effect of tarnishing NIDA.

Leshner, in an interview with Salon, shrugs off the criticism. Fanatics for a zero-tolerance policy attack him, too, he says, although the evidence he presents for this is tame. Last year, after he revised a NIDA pamphlet to remove poorly documented claims that marijuana diminished male sex drive, angry parents accosted him after a congressional hearing, claiming he was encouraging marijuana use, Leshner says. “I walk a line, and I might be walking it pretty well, because people on both sides hate me,” he says.

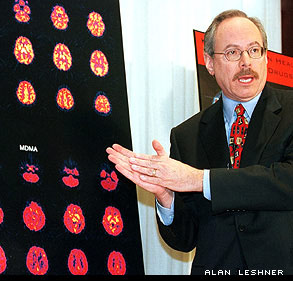

Mostly, the Leshner line is that people need to be shown exactly what the detrimental effects of drugs are with the most sophisticated public relations tools available. A campaign against ecstasy, the rave pill of choice whose popularity has skyrocketed in recent years, epitomizes the controversy over Leshner’s anti-drug contribution: NIDA has been distributing a set of brightly colored postcards about the drug, with its Web address on the back, for wire racks set up at thousands of shopping malls, clubs and restaurants.

The centerpiece of the card shows parts of two brains side by side — photographs taken from a positron emission topography (PET) scan, technology that enables scientists to examine brain function in a live patient. The brain on the left — the brain of a non-ecstasy user — pulsates a radiant orange and yellow. The most prominent feature of the brain on the right is an estuary of dark, vacant black and blue lapping at a faded orange archipelago — the shrinking brain function of a chronic ecstasy user. The message is obvious, though unstated: Ecstasy destroys your brain — and here are the high-tech images that prove it.

The brain-scan images were mounted next to the podium when Leshner and McCaffrey held a news conference to launch an initiative against club drugs last year. Market research on their effects on teens won’t be back until March, but the NIDA Web site has gotten nearly 2 million hits.

“The images are wonderful educational devices,” says Leshner. “This is a picture that really lets you see the effects.”

But does it?

The PET scans were first published in a 1998 study in the Lancet by George Ricaurte and Una McCann, a husband-and-wife team at Johns Hopkins University who have worked closely with NIDA and have been studying ecstasy since before it was criminalized in 1985. Customs seized 3.5 million ecstasy tablets last year, and 8 percent of all high school seniors said they had at least tried it.

McCaffrey and Leshner are probably smart to be alarmed about this. Animal research shows that ecstasy damages serotonin neurons, which are key to emotion and memory. Human research seems to be showing damage, too. But it has been harder to study ecstasy’s effects on humans — you can’t just dose them, chop them open and look at their brains. Ecstasy fans tend to have a history of using other illicit substances, which muddies the data because researchers never know how messed up their brains were before they started popping the club drug.

The Ricaurte-McCann study was one of the first to try to sort some of these issues out. The team took a group of heavy ecstasy users who’d been abstinent for at least three weeks and injected them with probes that give off a radioactive glow when they bind with serotonin neurons. Since ecstasy causes these neurons to die in animals, the probes were expected to find fewer neuron endings to bind with in the human ecstasy users. Their brains would look duller in the PET images. And they did, at least in the image in question.

However, the study wasn’t quite as elegant as it sounded.

First, it was relatively small, and the population it tested was extremely drug-addled. The study compared 15 drug-free controls with 14 people who’d used ecstasy an average of 226 times. The study’s statistical analysis showed that heavy ecstasy users, on average, had fewer serotonin binding sites — suggesting brain damage. But even in this group, the differences weren’t that dramatic. In fact, there was a great deal of overlap in binding site levels among ecstasy users and controls.

Despite the small sample, both the researchers and Sheryl Massaro, the NIDA official who designed the cards, said they did not know which ecstasy user’s brain is depicted on the postcard. But it’s probably safe to assume that his or her brain was at the extreme end of serotonin nerve-ending depletion. “Certainly,” says McCann, “they picked an image that was dramatic.”

Because of the Ricaurte-McCann study’s imperfections, critics have claimed that the postcard is deceptive — a slick, high-tech update of the “this-is-your-brain-on-drugs” eggs that sizzled in a pan in public-service TV ads in the 1980s. “You show low-intensity areas black and it looks like you have a hole in your fucking brain,” says Kleiman, the UCLA professor. “That’s astonishingly dishonest.”

Charles S. Grob, a UCLA psychiatrist who has used low doses of ecstasy as a therapeutic agent, believes the Lancet study is one of various studies “touted by the media that have methodological flaws.” Grob challenges whether the neuronal depletion noted in these studies translates into permanent, disruptive changes in brain chemistry.

Leshner makes no apologies for the graphic club drugs initiative. “We missed crack cocaine, we blew it with LSD,” he says. When NIDA’s sentinel drug use surveys started to show ecstasy use was expanding, he adds, he felt he had no choice but to intensify a campaign against it and deploy all available ammunition.

Ricaurte, who along with many researchers is convinced that ecstasy is a dangerous neurotoxin, believes that a lot of the questioning of his work is orchestrated by critics like Rick Doblin of the Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies, a Boston group that promotes the positive effects of illegal drugs. Doblin and Grob, the UCLA psychiatrist, believe Leshner should fund research using far more modest amounts of ecstasy, particularly in therapeutic settings.

“I think it is really outrageous when Leshner says there’s no such thing as recreational drug use,” Doblin said. “Sure, there’s a risk someone could overheat and die at a rave. But that obscures the fact that 35 people died skiing last year. A level of risk is not inconsistent with recreational activity.”

But Leshner has a retort to that argument as well. “I don’t ski because I’m a vulnerable klutz,” he says. “If I knew I was vulnerable to the effects of a drug I would choose not to use it. But we have no way of knowing. There are no markers of safety that tell me how I’m going to respond to a drug. Kids don’t do subtlety particularly well. So you say to them, ‘This is recreation,’ and they think it’s swimming. I don’t think it’s swimming — the risk is substantially higher.”

Leshner uses the same reasoning to explain why he adamantly pushes an anti-marijuana message to teens. But despite that message, he seems to have quietly ceded some ground in the increasingly volatile battle over medical marijuana.

Donald I. Abrams, who heads the Community Consortium for AIDS research at the University of California at San Francisco, discovered how bullheaded Leshner could be on the subject when he tried, in 1994, to get NIDA support for a proposed study on marijuana smoking by patients with HIV-related wasting syndrome.

One of the odd paradoxes of NIDA is that while it generally doesn’t get involved in research into the medicinal qualities of illicit drugs, it controls the country’s only legal stash of research marijuana, which the agency grows on a farm in Mississippi. Other federal NIH institutes can fund research on the potential medicinal uses of marijuana, but only NIDA can provide the marijuana, and it does so only after conducting its own reviews of the proposed studies.

NIDA has turned down the requests of a handful of researchers who sought marijuana for therapeutic trials. Paul Consroe, a University of Arizona pharmacologist, went into partial retirement last year after spending a decade trying to launch a study on whether marijuana can alleviate cancer pain. “I was tired of banging my head against a brick wall,” he said.

A NIDA review panel also turned down Abrams’ proposal. Infuriated by NIDA’s actions at a time when thousands of San Francisco Bay Area AIDS patients were smoking pot to cope with aspects of the disease, Abrams let loose in an angry April 28, 1995, letter to Leshner:

“As an AIDS investigator who has worked closely with National Institutes of Health and the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for the past 14 years of this epidemic, I must tell you that dealing with your Institute has been the worst experience of my career!” he wrote. “The ‘sincerity’ with which you share my ‘hope that new treatments WILL be found swiftly’ feels so hypocritical that it makes me cringe.”

Eventually, though, Leshner and Abrams reached an understanding, and a pilot study with marijuana was funded by several NIH institutes, including NIDA — one of a handful of medical marijuana studies in which NIDA now quietly participates. Strictly speaking, however, the Abrams study wasn’t a medical marijuana study. “Our first study proposal concentrated on weight gain in marijuana smokers, but NIDA wasn’t interested in a study that might show medical benefit,” Abrams recalls. “Leshner said, ‘We are the National Institute ON Drug Abuse, not FOR drug abuse.”‘

Rather than examining whether marijuana helped AIDS patients gain weight, the revised study’s stated goal was to examine whether marijuana interfered with retroviral drug regimes, a hypothesis that surfaced because of NIDA-funded research at UCLA indicating that cannabinoids can damage parts of the immune system.

But the result was a study that achieved what Abrams set out to do in the first place. Not only did it show that marijuana didn’t seem to harm AIDS patients’ immune systems, but it also helped them gain weight. At the international AIDS conference in South Africa this summer, Abrams was able to report that in his study of 63 AIDS patients, the marijuana smokers kept their HIV loads low or lower than the control group — and that patients who smoked the drug had gained an average of 4 pounds more than those who hadn’t.

Leshner is sanguine about the deal. “Me and Abrams have become big buds,” he says. “Give me 20 marijuana studies like that and I could get them all funded.”

And Abrams, a hero to drug-war critics for his tenacity in pursuing the marijuana study, has done an about-face on Leshner and NIDA. “They were the enemy,” he says. “Now I’ve been working with them and they’re my colleagues.”

Of course, Abrams has a strong motivation to praise Leshner. He’s currently writing grant proposals for a new, $3 million University of California medical marijuana research project.

The funding for the project comes from the state of California — but the marijuana will come from NIDA.