When Gallup, the godfather of American polling organizations, released poll numbers showing a 19-point swing in the presidential race three days after its previous poll, journalists and pollsters alike scratched their collective heads. Though the polls have been volatile in the last two months of the presidential campaign, the notion that there could be such a dramatic swing in public sentiment in such a short period of time was difficult for many to believe.

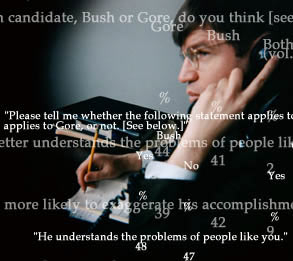

On Oct. 4, Gallup released numbers that showed Al Gore with a 51-40 lead. On Oct. 6, Gallup had George W. Bush up, 48-41. Tracking polls survey their respondents over a three-day period (some organizations even use shorter tracks), and are used to show the day-to-day evolution of a political race. They differ from regular polls in the number of people polled (tracking polls use samples that can be up to 20 percent smaller) as well as the amount of time used to gather the sample.

But Gallup’s two sets of numbers illustrated what some in the profession say is leading to the deterioration in polling credibility. “I have a bone to pick with the national polls,” says Mark DiCamillo, director of the Field Poll, a nonpartisan polling organization that focuses exclusively on California. “They’re destroying the image of our profession. Take Gallup — they’re the granddaddy of polling. For them to bring the profession down is the ultimate irony.”

Part of the problem, DiCamillo says, is that all polls are treated as equal. That problem has been exacerbated by the explosion of cable news and Internet outlets, which have increased the appetite for the political horse-race, and the numbers — the odds — that are placed on them.

“The media are the worst,” he said. “They’re part of the problem, no question.” But, DiCamillo says, the problem isn’t just that news organizations devour polling numbers without thorough analysis, but that they all have commissioned their own polls. “Everybody has to have their own poll. More may be better as long as they’re all good, but these new polls are not that great. But now, any media property worth its salt has to have its name on a poll.”

The problem with the influx of new polls, DiCamillo says, is with their methodology. How a poll is conducted can dramatically affect the end result, and the quality controls on polling have slipped with the rapid increase in their numbers. “Most of us who have been doing this for a while know each other,” DiCamillo said. “We know who the goods ones are.”

Frank Newport, editor in chief of the Gallup Poll, defends the use of tracking polls, which Gallup has used since 1992. “This is a science. Tracking polls are just polling done daily,” he says, shrugging off some of the negative reaction to Gallup’s methods. “George Gallup was writing about adverse press reaction to the polls in the 1940s. Congress even kicked around the idea of trying to ban polls. This year, we’ve had individuals asking if tracking polls are necessary. Our decision is, yes, it’s both important and interesting.”

DiCamillo argues that, generally, a polling sample gathered over five days or more is going to provide a more accurate sample than a three-day tracking poll, which is liable to pick up temporary fluctuations in voter sentiment. Newport argues that in a race like this one that is moving so quickly, there are disadvantages to staying in the field too long.

Prominent pollster John Zogby can’t resist a dig at Gallup, but blames the perception that polls have been erratic largely on the media.

“Believe it or not, if you take Gallup out of the picture, the rest of us are fairly stable and pretty much in the ballpark,” Zogby said. “If you go back to ’96 when there was real volatility, even then, if a poll came out that had Clinton ahead by 15 on a Tuesday and 11 on a Thursday, nobody paid attention. But when you’ve got the polls showing a close race, then that 4 point swing becomes more significant. I think that’s what we’re seeing. It seems to me that all of us do 98 percent the same thing. It’s the 2 percent, the little bit of art in the business, where some of us have differences.”

“They’re not all over the place,” says Gallup’s Newport. “If you isolate polls taken at the same point in time, generally, they’ve showed roughly the same thing. People who track, like us, we see times where Bush has polled ahead. We see times when Gore has pulled ahead. There are different methodologies, and some other differences, but I would say if you take a broader view, you would find general consistency with the polls.”

Polls are used as tools by political campaigns as well, particularly tracking polls that can show one candidate surging temporarily and dramatically. Last week, the Bush campaign held a conference call with California media to announce a new Zogby poll showing Bush within 6 points of Gore, with Gore clinging to a 45-39 lead. The day before the Zogby poll was released, a new Field Poll came out showing Gore hanging on to his 13 point lead in the state.

Bush California spokeswoman Lindsay Kozberg says that the Republican Party’s Victory 2000 “purchased the questions on the Zogby survey,” asking the pollster to measure the presidential race. Unlike the Field Poll which gathered their data over 10 days, the Zogby poll was a 3-day track between October 6-8.

The Zogby poll was commissioned by California GOP senate candidate Tom Campbell. Victory 2000 chipped in to ask Zogby to monitor the presidential race as well. But partisan polls are often disregarded by independent pollsters, criticized as means to a predetermined end.

The phrasing of questions, the sequence that questions are asked in and whether a pollster polls in Spanish in states with large Latino populations can all affect poll results. DiCamillo pointed to the National Council on Public Polling’s list of 20 questions reporters should always ask about a poll as a good primer. Who commissioned the poll, for example, is fundamental to interpreting the result. Knowing who paid for the survey and how the respondents were selected is also central to reading the poll results, for example.

The Bush conference call also came on the heels of a multimillion-dollar ad buy by the Bush campaign, which has struggled to convince the California media that the state was still in play.

Kozberg says that while the campaign certainly hoped the new poll numbers would help build momentum for Bush in the Golden State, “the Zogby numbers were consistent with the internal polling numbers of the Bush campaign. It’s also substantively consistent with the feedback we’ve been getting.” She says that while the Field poll is “a well-respected California institution, to see no movement in the Field Poll whatsoever while the national polls show dynamic change should lead people to question whether the poll is accurate. We just don’t see how that’s possible that the rest of the nation is hearing and absorbing the governor’s message and California voters aren’t.”

But DiCamillo says that’s exactly what’s happening. His poll showed a 13 point lead for Gore in August, and a 13 point lead on Oct. 10. The latest Field poll had Gore at 50 percent, with Bush at 37, the exact same percentages as the August poll. “California has had no movement,” he said. “Zogby is a private poll. It’s the Republican Party. My bias is, I don’t buy any private poll. They have an axe to grind. I don’t care how professional the guy is, those private polls leaked to the press are done for a reason — for fundraising purposes, to rally the troops — whatever.”

For his part, DiCamillo says that monitoring the state polls gives a more accurate account of the race than looking at a national poll. “I’ve had a bias against the national polls going back to 1980. The national polls were showing that the race would be close. But clearly by looking at the state by state polls, Reagan had it. It was just never close.”

Many pollsters lay some of the blame for the polling industry’s bad PR at the feet of the media. As with other kinds of scientific reporting, they say, reporters covering the polls are not casting a critical eye, or asking the right questions about a poll’s methodology to get a sense of whether a poll should be trusted.

“Generally speaking, it would not hurt us if the media was able to compare and contrast and spend a little more time looking over the data,” Newport said. “I would say that there are often snap judgments in the reporting about polls. Well-meaning journalists are in a hurry sometimes.”

Newport says that reporters often misread the differences between the polls. In reality, he says, each candidate’s percentage should be measured individually. So instead of comparing the spreads between the two candidates, reporters and voters should focus on Zogby’s 45 percent for Gore and Field’s 50; Zogby’s 39 percent for Bush and Field’s 37 percent.

“When you look at the difference between margins, you’re doubling the perceptions of margins between the polls,” Newport said. “What you should be comparing is the vote total each candidate gets in the two polls, not the spread.” Newport explained that there is a margin of error for each individual result that is taken. So there is a margin of error in the Gore numbers, and a margin of error in the Bush numbers. Focusing on the point spread, therefore, doubles the margin of error.

But a new host of challenges has also manifest in the polling biz, which are changing the profession. For one, voters are becoming less receptive to talking to pollsters. Zogby said when he started polling in 1984, the response race was about 65 percent. Now, he says, it is about 33 percent.

And, Zogby says, people don’t answer their telephones as often as they used to. “The telephone isn’t obsolete but it is getting more difficult to use. The response rate is lower than it was, but that only means it takes us longer. It hasn’t affected the quality yet, but I’m assuming that next year, more of my polling will be Internet polling.”