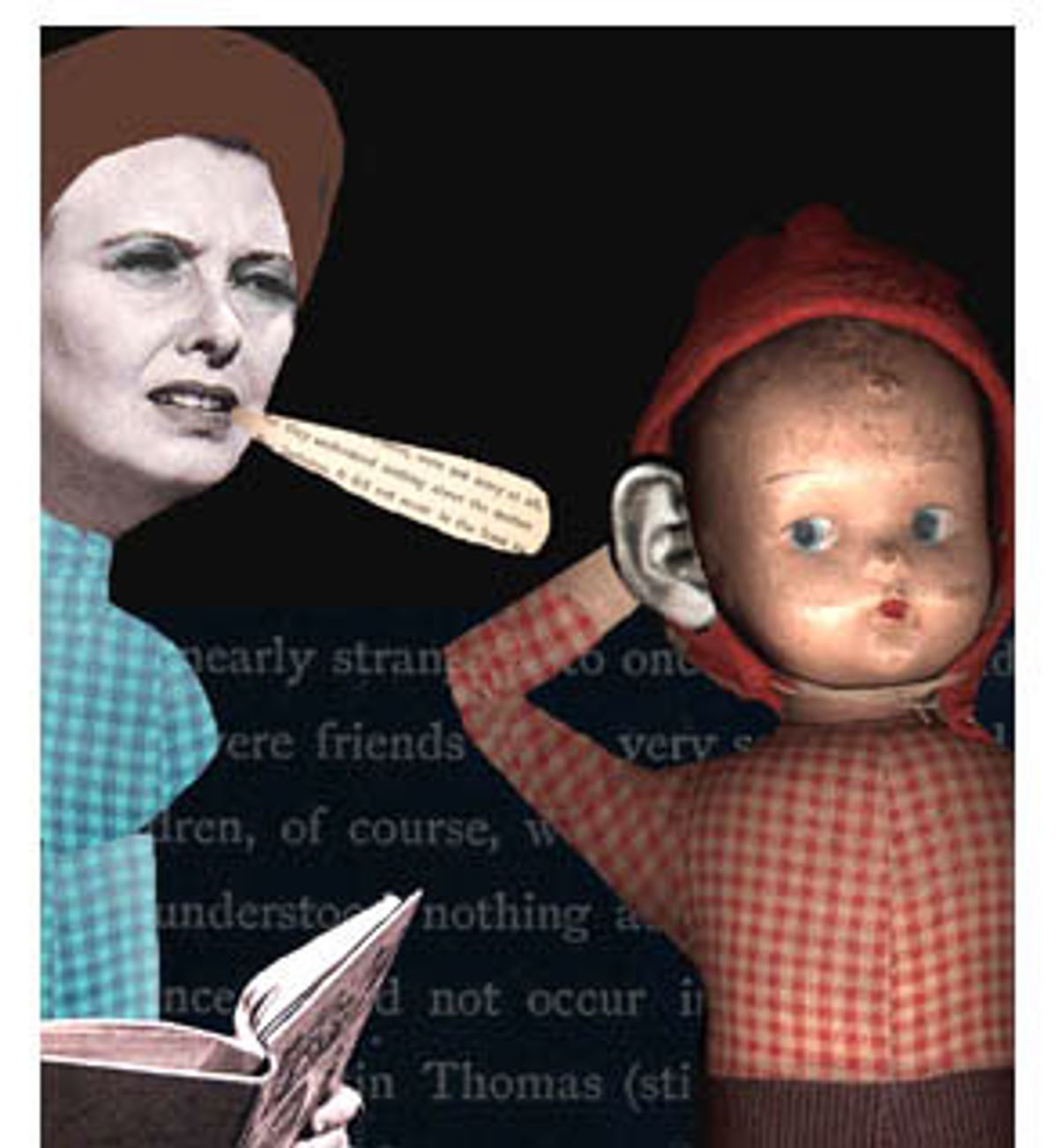

Today I committed an act of violence against my child. The act was premeditated and carried out with the help of my husband. It is something we have been doing as a family for two years. We have no intention of stopping, and luckily, we won't be punished for the violence we are inflicting, unless a specific branch of Freudian theory is made into law before my son learns to read. In that case, I will be incarcerated for indoctrinating my child in the baleful system of literacy.

That's right. Add this to your list of sins, Mama: teaching your kid to read. I found out just the other day that I was participating in a conspiracy to constrict my child's understanding of and expression in the world by reading to him. I learned this while attending a conference on books where, for the first day, we focused on Jacques Derrida, a French theorist who is known as the Daddy of Deconstructionism, and his translators.

It was Peggy Kamuf, a professor at the University of Southern California, who revealed the terrorism inherent in reading to children. She presented a paper (she read it aloud!) to a crowd of about 40 people, most of them academics, in which she insisted that teaching kids to read initiates them into the patriarchal construct of the family unit and society at large. This initiation is, according to her, a brutal and painful rite of passage. It is so painful, she added, that people don't even recollect learning to read. The memory is repressed, said Kamuf, because the act is violent.

During a discussion following her presentation, Kamuf kept referring to the violent moment in which a mother teaches a child to read and I kept visualizing myself on the sofa, reading to my son. I finally raised my hand, planning to derail Kamuf's theory by suggesting that speech, not reading, is the point of entry into the jail of cultural structure. Unfortunately, the session ended before I was acknowledged, so I approached the podium and announced that I had a 2-year-old and it seemed to me that speech was more the moment of brutal indoctrination into the culture than reading was.

"Of course, of course," she told me. "We all know that."

Huh? I wondered. If we all know that, then why did she declare reading aloud as the singular act of linguistic brutality? And who buys this line, anyway? Come to think of it, my spin is just as ridiculous as hers. The whole idea that kids are hurt, not served, by words is stunning -- splitting hairs about when the tragedy occurs is downright heinous.

Isn't everything that a mother teaches her child going to push that little creature further from the wild? Of course. Is that a problem? I don't think so. My husband and I would like our son to poop in the potty. We don't want him crapping all over the house so that he can experience his animal self. We want him to learn to use a napkin and to learn other table manners. We want him to go to bed easily. We want him to learn to read. All of these things cleave him from his animal self and force him toward a norm he is likely to combat on a daily basis, since he is, like us, human.

We struggle with our mortal and moral desires, and our beastly tendencies. We want to be comfortable and successful, kind enough to each other and our neighbors to be respected. We need to sleep, to eat and to climb to the top of every pile we encounter. And while we're busy teaching our beautiful boy animal how to behave, we can try to show him that outright greed and selfish ambition are impolite, as well as attributable to our animal roots, which, by the way, is no excuse for maiming others in a climb to the top.

Unchecked ambition is perhaps what forced Kamuf to blame mothers and reading for civilizing children. (She seemed to leave fathers out of this particular transgression.) From what I know of the small, high-pressured circles of academia, she must climb to the top if she wants to be someone. And coming to conclusions that sound new, even if they are inaccurate, does cause recognition.

The men who praised her after her talk appreciated Kamuf's insight into reading theory. And while they, her colleagues at other institutions, are not responsible for her promotion, their esteem will help keep her position secure. On the basis of her need to succeed, I can forgive her for putting phrases and ideas into pools where I think they do not belong. But poor reading! An activity that appears to be on the endangered-species list doesn't deserve more measures against it. If reading is what civilizes us I am glad to be civilized.

Fortunately, this odd onus is unlikely to shatter any of the standing, albeit conventional, theories about literacy. I certainly have no plans to interrupt the daily, nay, hourly, schedule of regular beatings with printed words that I inflict on my child. He likes them so much he now asks for them himself, and the scars have assimilated into his body. Indeed they are completely healed and under his skin, where none but the literary theorists can see them.

Luckily these folks keep their eyes on texts, not on empirical data, and the practitioners of early childhood education do not turn to theory departments, and the dubious delights of deconstructionism, when looking for new ways to work with children. They look at children, perhaps with less love than I have when I look at mine, but none of our eyes see violence when we watch adults on sofas with children, reading.

Shares