In the 1970s and ’80s, Sam Shepard was an artist-in-residence at San Francisco’s Magic Theatre, premiering many of his most famous works there. The Magic is now again host to a Shepard world premiere, “The Late Henry Moss.” Two factors have propelled the production into a huge media event: The author himself directs, and he has assembled an amazingly high-wattage cast. Nick Nolte, Sean Penn, Woody Harrelson and Cheech Marin headline, veteran character actor James Gammon takes on the title role and Sheila Tousey plays a lusty Indian woman with mysterious powers. The Magic moved the show from its small home stage to the 740-seat Theatre on the Square, near San Francisco’s Union Square. Still, the five-week run is already sold out. (A small number of same-day rush tickets are still available for each performance.)

In one sense, “The Late Henry Moss” is a culmination of Shepard’s playwriting, both a summing up of and an expansion of the themes and issues he has explored throughout his career. There are the warring siblings of “True West,” the hidden family secrets and wounds of “Buried Child,” the symbolism of “A Lie of the Mind” and the themes of the frontier’s end, the damage fathers do to sons and all the macho-mythic desperation and attempted poeticism that exist in so many of his works. But Shepard doesn’t enlarge these themes; he isn’t exploring anything new, original or insightful. It’s as if a college student completed an assignment to write in the style of the playwright. Shepard’s halfheartedly cribbing from himself, and it makes for a very long evening.

The show opens with a quiet, funny malevolence. After a preliminary tango across the stage by Gammon and Tousey, we see Earl Moss (Nolte) sitting at a table in a secluded, rural New Mexico house, drinking bourbon and smoking, while his younger brother, Ray (Penn), stands with his back to the audience, swinging a socket wrench, its clicking ratchet the only noise. He’s gazing at a corpse wrapped in a sheet on the upstage bed — the pair’s father, Henry.

The brothers haven’t seen each other in many years: Earl fled the family long ago after a drunken rampage in which Henry terrorized and battered his wife and broke out the windows of their home. But there’s something fishy in Earl’s description of Henry’s death. He tells Ray that Henry’s neighbor, Esteban (Marin), had called him when Henry left the house in a taxicab and didn’t come back for a while. Earl flew in to discover Henry already dead. Esteban, later making his usual delivery of soup for Henry, unaware that he has died, supports Earl’s story about the phone call, though it’s clear he’s covering up something for Earl.

Esteban explains that Henry, flush and drunk in the aftermath of receiving a government check, called a taxi to take him and Conchala (Tousey) — a woman with whom he occasionally caroused and slept — on a fishing trip. Ray subsequently interviews the cabdriver (Harrelson), who relates a somewhat different narrative.

There are several extended flashback sequences that get us to the “truth” of the matter. We watch Earl grapple with his guilt over cowardly abandoning his mother and brother while Ray wrestles with his anger and sorrow. There are stretches of ironic, banal dialogue. (Ray to the cabdriver: “You’re nothin’. Just like me.” Henry to Earl: “You know me, Earl — I was never one to live in the past.”) These are occasionally interrupted by desert heartland poetry. (Earl to Ray: “You jump all over him like a cold sweat.” Earl to Esteban: “I am nothing like the old man: We’re as different as chalk and cheese.”)

Plus, there’s Conchala, Shepard’s woman-myth character. In one flashback, we find out that when she and Henry first met, in the jail drunk tank, she pronounced Henry dead: “Dead for 20 years, a dead man living in a dead house.” (Shepard’s telling us that women define men, even holding the power of life and death over them.) Henry and Conchala return from the fishing trip with one tiny, 4-inch catch. Conchala strips down to a slip, takes a bath (still partially clothed) and puts the fish between her legs. It comes back to life; she puts it in her mouth, and swallows it whole.

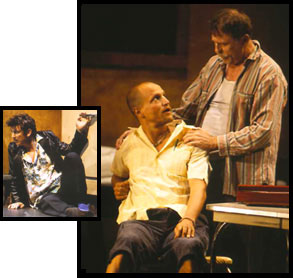

Criminy. Nolte and Penn don’t embarrass themselves, but the straitjacket roles and dialogue lead them to turn inward, and their performances don’t project. There’s no sense of life, just generic, “adult children of alcoholics,” abuse-survivor self-loathing and recrimination. Penn has a nice moment in the first act fighting back tears over his father’s death, but you won’t see it from the balcony. Nolte matches his bristly bourbon voice to Gammon’s whiskey growl, underlying their shared history. The secrets that get exposed are surprisingly anticlimactic; you get the Sturm und Drang of melodrama without the kick, and the brothers have nowhere to go dramatically.

Marin is funny for a time as the obsequious neighbor who cooked for Henry and sometimes borrowed his woman, but as the evening wears on, he starts to resemble the stereotypical Mexican cook in a western. Gammon, in the flashbacks in which Henry is alive, bellows his lines at the same level, whether denying Conchala’s declarations of his death or accepting them. His makeup, for some unfathomable reason, is smeared like mud on his face.

Harrelson, however, glows with an actor’s love of craft as the unnamed taxi driver. Saddled with the sometimes-dangerous traits of being both hyperfriendly and a wimp (leading him to prolong relationships he should flee), Harrelson’s cabbie is constantly in motion. His arms never hang at his side; his hands keep fluttering up as if he’s afraid they might cause offense if they ever landed anywhere. He shifts from foot to foot, prattling on about his dreamland, the lucrative midnight-pizza delivery in Norman, Okla., where every university dorm door is opened by a Miss America student who wants to screw you.

The cabdriver’s jittery, invasive energy drives Ray batshit, and he commands the driver to remain in one particular spot, virtually a physical impossibility for the character. (Harrelson humorously has to keep retreating to the designated space, measuring from the doorway with his extended arm to make sure he’s in the exact location.) And even when he’s required to howl and whine in outrage at the way he’s treated (over and over again), he’s astonishingly entertaining: “I never should’ve left Texas,” he moans. “You get raised in a friendly place, you start to thinkin’ everyone’s friendly.”

In Shepard’s direction, you can see where easy compromises have been made. Characters not in a flashback sequence exit off the front of the stage, fully lit, violating the boundaries of the theatrical space. Props and set pieces shifted during the various recollections are dealt with awkwardly when the present returns. There’s also no real rhythm to the production, as if the actors worked on their parts individually and were thrown together only as the opening approached. (Several lines get stepped on as well.) Shepard discordantly slapsticks around with two funeral-home attendants as if they were Keystone Kops — they sport black suits and sunglasses, peek out insanely from the bedroom curtain and drop the corpse on the floor.

The show is heavily amplified, but the voice levels shift depending on how close the actor is to one of the many mikes. (A friend sitting farther back than I said it was occasionally difficult to hear Penn and Nolte.) Songwriter T-Bone Burnett provides the lovely live guitar accompaniment. Despite the marketing excitement, “The Late Henry Moss” is no triumph for either Shepard or the Magic. But Harrelson’s funny, sexy, energetic performance gives off a heat not otherwise found in Shepard’s dim, worn desert tale.