In Alfred Hitchcock's "Vertigo," Scotty is hired by Gavin to follow Gavin's wife, Madeleine, who may be disturbed, who may even believe that the melancholy spirit of Carlotta Valdes -- a 19th century suicide in "old" San Francisco -- has entered her life. Pretty simple and straightforward, or so it seems, except that Scotty is an ex-cop, a man who had to give up the job because of his fear of heights, his vertigo. Yet he lives in San Francisco, where you only have to nod off to think you are falling.

Well, he follows Madeleine: She's a bright blond dressed in gray, except at Ernie's restaurant, where she wears scarlet and black and pauses so that Scotty and the camera can drink her in. For half an hour or so the film is all about following and watching, in a San Francisco where pursuit and parking spaces offer no impediment to the magical, unspoken attachment of the plot. But in film, you can hardly watch or follow without falling in love -- the spectacle touches the private eye.

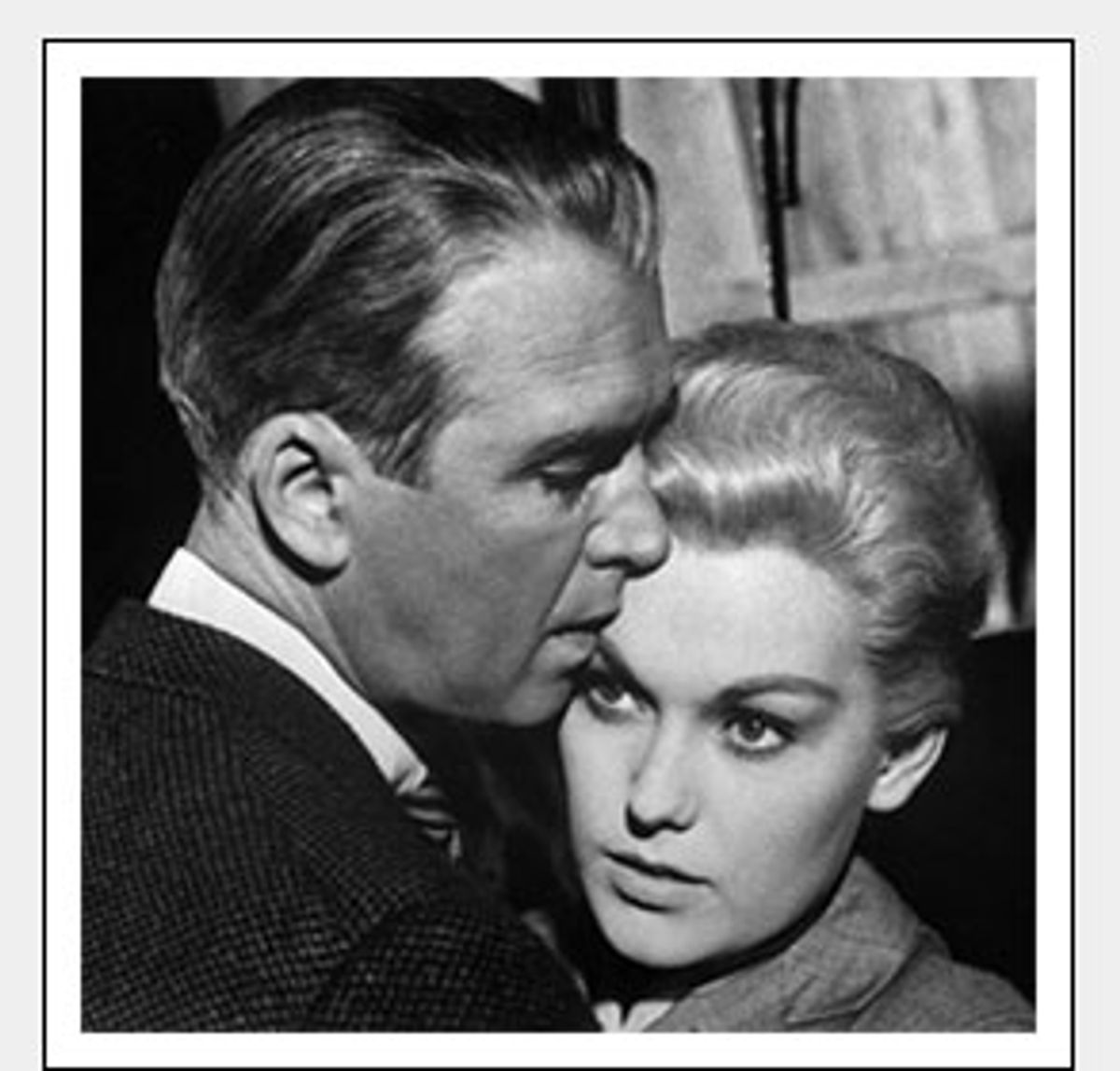

Now, actors are involved: Scotty is James Stewart, and Madeleine is Kim Novak. This is more than helpful, for he has intelligent, if incipiently wounded, following eyes, while she is a blank beauty, unaware of the idea of being watched. Yet, as we learn, both are playing their parts.

Well, Madeleine goes down to Fort Point, beneath the southern end of the Golden Gate Bridge, where the waves beat at the corner of the land. And her gray suit slips into the water -- that old suicidal feeling welling up again. Scotty goes in after her, hauls her out -- Madeleine is a ghostly creature -- yet Novak in wet clothes is plainly a load to carry.

He takes her back to his apartment. She has fainted, or passed out -- I don't know what suicides do in the aftermath of a spent attempt. Maybe she is only feigning faint, for this Madeleine -- I'll break it to you, she's really a plain Judy, with red-brown hair -- is on a mission to seduce Scotty, to lead the ex-cop astray. Gavin (remember Gavin? aren't all great films like dreams?) put her up to it.

So Scotty takes Madeleine/Judy home, and -- we don't see this; this is 1958 -- he removes her wet clothes and puts her on a sofa beneath a blanket. Her clothes are hanging up in the background when Judy "comes to." They are Madeleine's clothes, but it is Judy's body that the cop has seen or tried not to see, as if he were an apprentice mortician. But now, for the first time, Novak acquires a greedy, carnal stare, as if to ask, Did you see me? You saw me, didn't you? And Judy, after all, needs to stand up for herself. Indeed, see "Vertigo" enough times and you may realize in this scene that Judy is beginning to fall in love with the mournful cop. But all she has to do for the moment is let Scotty feel that he gazed upon her body in unwatched liberty or innocence -- the voyeur craves not to be detected (otherwise he is a peeping Tom). Looking needs that peace, that dark, to become perilous.

Of course, Judy didn't faint. She felt the warmth of his looking, which is better than a blanket. Without opening her eyes, or even peeping, she felt she was loved, or that her character was loved. The rest is tragedy.

Shares