I was lucky to be sent a copy of Dalton Conley’s “Honky” in galleys six months ago. Lucky because it’s a wonderful book but also because, as a memoir describing Conley’s experiences growing up in 1970s New York as a white kid in a largely poor black and Hispanic neighborhood, it confirmed some of the strangest parts of my own childhood experience. I’d just been searching for a way to give some of this material a voice in a new novel, and Conley’s book helped.

Conley is a trained sociologist and a career academic teaching at New York University. His book raises his own anecdotal experiences into a sociological light, making it a kind of memoir-plus. Yet it seemed to me the book ultimately comes down on the side of the personal, and on those terms it’s a triumph. Like any novelist arraying himself with inspiration for a long voyage into unknown territory, I took it as a hopeful sign.

A month or so later, I was lucky again, in coming across Phillip Lopate’s essay “The Countess’s Tutor” in the fifth anniversary issue of Doubletake magazine. Lopate’s description of his family’s move from Williamsburg, a Jewish neighborhood in Brooklyn, N.Y., into largely black Fort Greene echoed Conley’s experiences, and my own, uncannily. It was all the more striking for the way certain rituals that had seemed so particular to my 1970s experience were already evident in the mid-’50s. Just like Conley and me, Lopate had been repeatedly posed an inexplicable and unanswerable question by the black and Hispanic kids on the streets where we lived: “What you lookin’ at?”

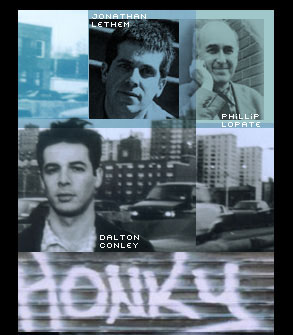

The three of us met in Brooklyn over coffee, cookies and a tape recorder in November to talk about it.

— Jonathan Lethem

Phillip Lopate: I really liked [Dalton’s] book. It’s not easy to do the adult voice but keep the child psychology. And you got a plotline going in spite of this choppy episodic stuff that can happen when you’re talking about your childhood: “Then we did this, then we went around doing that.” There’s humor and perspective. Fortunately, Dalton did so many bad things when he was a kid that you didn’t have the problem of a goody-goody character. You had an embarrassment of riches.

One of the hardest things in writing about the kind of background we’ve had — being a white kid in a minority neighborhood — is that there’s a tendency to hero-worship the blacks or Hispanics and, underneath that, to patronize them and not, on some level, to be honest. You showed how attractive, for all kinds of reasons, black culture and Hispanic culture were for you, but you also showed that character putting a knife to your head.

I remember when I was much younger, and read an essay by Gregory Corso in Esquire where he talked about being white and being beaten up by black kids. It was the first time I’d ever read anything like that. You don’t know where to go with those feelings. What are you going to say? “I was oppressed too.” “Um … my oppression to me is the same as your oppression.” That’s why I think your tone of irony is so important.

Dalton Conley: Who actually knows why you got the crap beat out of you? I mean, all kids beat each other up. I’m sure I would be a very different person if I’d been 6-foot-5 and 220 pounds of muscle. The whole dynamic would have changed then, because toughness would have been on my side, regardless of race. It’s hard to know what went on, because I was a skinny white kid. In some ways I regret the way I titled the book. I wanted a punchy, quick title. But it makes people who haven’t read it think it’s “Oh, poor white boy complaining about reverse racism and being singled out and called ‘honky’ all the time,” and that’s not what I wanted to get across at all.

Lopate: No. But it’s not a bad title for a book.

Jonathan Lethem: This is exactly what I’m wrestling with: the difference between ordinary bullying and bullying with racial overtones. And then this — call it reverse racist bullying, for lack of a better term.

In those moments the wider context — that my tormentors were powerless in society and that I was a representative of the powerful majority — was right there with us, even at age 10, 12, 13. The impossibility of ever claiming racism as an issue was something I felt. If I pointed out what was going on I was automatically a racist. That silenced me.

Lopate: It often shocked me that I was not being bullied. I was the only white kid at summer camp, and nobody picked on me. Why would they be even remotely threatened? There was no reason to pick on me. I felt a little bit ignored. It was their world. I experienced this confusion — feeling scared and threatened and wondering why there wasn’t more tension. And since I’m Jewish, I was threatened as many, if not more, times by the Irish kids, who waited outside Hebrew school, as by the black kids.

Conley: When you would go to, say, a different black neighborhood, to Harlem or to a different area of Brooklyn that was predominantly black, did you immediately feel a different dynamic? I know that when I would go to, say, Spanish Harlem — which is almost demographically the same as the Lower East Side — just because it was unfamiliar, and because I didn’t see the same faces hanging outside of the Puerto Rican social clubs as I did in my neighborhood, I did feel threatened in that way, which is sometimes remarkably absent in your own home area.

Lopate: I know what you mean, because where I grew up, in a black neighborhood, I definitely felt that people knew who I was, that I belonged. But a friend of mine who went up to Harlem one day was robbed, because everyone knew he didn’t belong there.

Lethem: I think there are invisible zones in neighborhoods. I knew when I was moving from the terrain that was dominated by the kids from Wyckoff Housing Project, as opposed to the kids from the Gowanus houses, because they had different turfs, and some of them knew you and nearly had an investment in protecting you. You were OK because you were recognized. Those invisible codes were at work.

When I first lived in this neighborhood, in the early ’70s, it was before there was an absolutely racial divide inside public housing. I had a couple of white friends inside the Wyckoff houses.

I knew a Jewish kid who lived there with his older brothers and his parents. The oldest of the brothers wasn’t tough, just older, a big chubby Jewish kid, and when I visited he would walk me out of the housing project. He knew he had to. He had his turf and he could escort me back home.

But it strikes me that before those codes are in place, there’s a degree of teaching that goes on. In Phillip’s essay where he writes about that question: “What you looking at? What you looking at?” I felt such recognition. I remembered how I felt I was being initiated into codes of deference — that until I’d learned how to move through the streets, I was going to be confronted.

Lopate: By the way, what is the solution to that question, “What you looking at?”

Lethem: Well, it’s by definition an unanswerable question. That’s the trick to it. You caught that beautifully in your essay: “How am I supposed to answer? What if I were looking at you, what would it mean? Why do I have to try to answer this question that has no answer?”

Conley: When you’re alone, or in that sort of street-level interaction, somehow the societal-level paradigm always gets flipped. I don’t know if it’s because when you’re poor and a minority in the United States that you’ve got nothing to lose, so just growing up that way makes you tougher. But it’s likely going to be the person who’s in the dominant group of society as a whole who acts very scraping and deferential in that kind of situation and says, “Nothing” when they’re asked, “What are you looking at?”

Lopate: You know, it was absurd, because I got so involved with jazz and blues, and I would walk down the street thinking, “I’ll tell them that I like jazz and blues.” And I had an almost scholarly relationship to the jazz and blues and I had a lot of black friends in high school, and they’d come over to the house, and I’d play them these things like the Five Blind Boys of Mississippi and they’d be so embarrassed. They’d say, “That’s the stuff my grandmother listens to.” And even when I was playing Charlie Parker, they had moved on. They were listening to organ and saxophone combos that were playing in Harlem. They weren’t listening to this. I had become a “Ph.D. in spadeology,” as they used to say.

The thing about power, though — I had an experience when I was about 13, 14 where my parents had a camera store near Myrtle Avenue, which was right by a big, black public housing project.

And they would send me in to try to collect, with these packets of photographs that had not been picked up — because people would send their pictures in, but then they didn’t have the money to collect them. So I’d knock on the door, and I’d hear the sound of pure terror. “It’s the man!” And I could have been 6-foot-5, I could have been the landlord, as far as they were concerned. They were behind closed doors, scurrying around saying, “Don’t open it!” and “What are we going to do?” In that situation it was very clear who was in the power seat.

Conley: I think sometimes it could break either way, in the sense that, for example, being called “honky” or any sort of racial epithet doesn’t work. It just sort of falls flat, like a bad pitch, compared to the reverse.

Something I talk about in “Honky” is the issue of “cultural capital” — a term sociologists use, which describes how my parents had a certain middle-class status no matter how little money they had. For example, when my local school got so bad, they might not be able send me to private school, but they could get a friend of theirs on the West Side of town to get me into the Greenwich Village school by lying about our address.

Coming from a family of artists, I knew all these totally useless references, in terms of any objective standard. But if I were to go to college, the fact that I knew who Jackson Pollock was would help me out in the interview. And so on.

Ironically, I think I was also advantaged because I sucked off the cultural capital of the neighborhood, in the sense that thinking of a quick retort to “What are you looking at?” or “Your mother’s so stupid she tried to alphabetize the M&M’s” was the perfect training for being an academic, for being a professor. That’s what we do. We sit around snapping on each other.

Lopate: I think in a way what you’re talking about, and again I identify with this, was your parents were bohemians. And it’s a strange class.

Lethem: I think it stands outside class …

Lopate: It pretends to be outside class. There’s no such thing as outside class, but it pretends to be, and there’s a kind of reverse snobbism. Just like my parents said, “Well, we’re living in the ghetto, but we’ve got the Bach records, and we know who Jackson Pollock is … We’re more sensitive.”

Lethem: Right, sure. Our parents cultivated an aesthetic of renouncing the things that were seen as middle class. I didn’t understand that we were as poor as the people in the neighborhood around us, but we were. I was insulated from that understanding by the book-lined walls and the people who would come over for dinner, the things that connected us to the world.

In fact, it was an enormous advantage when I finally got to college and met my ostensible peers, who were from the middle class but were often much more culturally deprived than I was.

Lopate: When I got to college, I went to Columbia, and I could not stop talking about the ghetto. And they would say, “Come on, Lopate, relax, you’re not there anymore.” Meaning, “You don’t have to be scared.” I wasn’t scared, I was boasting. And I felt like they didn’t understand something that was so important, that was reality. So I kept bringing the ghetto along with me.

Conley: I think you were more self-aware as a kid. Because for me it was quite the opposite. I longed for the lawns, the middle class, and when I came back from college after the first year at Berkeley, I asked my mother, “How could you ever raise your kids in a place like this without even grass and trees and a backyard? You’re so selfish.”

Now, of course, I would never have traded it for the world. I could never leave New York. I’m trapped here because of this experience, I think. And in some ways it’s very limiting. I’m envious of people who can feel comfortable in the malls and the backyards of suburban America.

Lethem: I grew up in a sort of hippie-Utopian atmosphere where my parents taught me to be oblivious to race. What I couldn’t have been prepared for was the way the community around me insisted that I learn to see myself as white. Even though I wasn’t insisting on their racial identity, they insisted that I understand mine. And they named it. I was the white boy. And I could never have produced the words “black boy.” I’d been trained it to feel it was unsayable.

Lopate: What’s your religion?

Lethem: My mother was Jewish and my father is a WASP from the Midwest.

Conley: Exactly the same.

Lopate: I gotta say, both my parents are Jewish, and I never thought of myself as white, I thought of myself as Jewish.

Conley: I never thought of myself as Jewish, I always thought of myself as white. Race so trumped any differences between ethnic groups within the white population.

Lethem: I think I bridge your two experiences. In Phillip’s essay there’s this older idea that there were many ethnic zones — Italian, Jewish, Irish, Puerto Rican, black, Polish. Then there’s Dalton’s experience, which is essentially being in a neighborhood where the only issue is skin tone anymore.

In my childhood, by chance, I moved from one to the other. From first to third grade I was at a school where there were only blacks, Puerto Ricans and a scattering of motley hippie kids, like myself, who were white. That was Dalton’s reality, where the only question was, “Oh, I’ve got white skin.”

Then, for fourth grade, I moved to Carroll Gardens, an old Italian enclave [in Brooklyn]. There I was no longer in the minority by skin tone. But I was met with this very self-aware, self-defining majority of Italian kids, who didn’t welcome me either. They introduced me to those finer distinctions that belonged to the older Brooklyn, to Phillip’s childhood. “Oh, you’re Irish, you’re Italian or you’re a Jewish kid. Or we can’t help you if you don’t know what you are.” Which was sort of my problem.

Later I realized that the kids from the black housing project on the edge of the Italian neighborhood recognized the difference, too. My brother tells a story of being on Court Street and being surrounded by a bunch of black kids, who were ready to shake him down but weren’t certain he wasn’t Italian. And they said, “Hey, you a white boy or you Italian?” And my brother’s response was, “Well, wait a minute. What do you mean? Those Italian guys are white, too! If you’re going to take my money, take their money, too.” But the black kids didn’t see it that way.

Lopate: Oh, sure, they’d come after them with baseball bats.

Lethem: Yeah. Whereas you and I, Dalton, as the Jewish bohemian kids, whatever we were, there was no team with baseball bats to take vengeance for us.

Lopate: It definitely is quasi-generational. I was born in ’43, I came up in the ’50s, at a time when Jews were still very black identified. There was all this “Let my people go,” and my parents had the Paul Robeson records. There was this feeling that the Exodus story and civil rights were connected. There was a whole involvement in the NAACP, etc. And this was before the big falling out occurred in about ’64.

So if my parents taught me anything, it was to mistrust other whites a lot, and blacks somewhat, but not as much as other whites.

Lethem: My parents, who are about 10 years older than you, Phillip, had the same instinct, but perhaps it had just then become obsolete. Certainly the blacks in the neighborhood we moved into didn’t honor it.

Lopate: I don’t think the blacks honored it in my neighborhood, either. As Baldwin says in his essay about uptown, “Blacks see the Jews as a frontline of bill collectors.” But culturally, we felt a warmth. It didn’t last forever, but it was part of the scene.

Conley: Mine are about five years older than Phillip. And I think that in some ways, they probably had some of the same attitudes, but didn’t know at the time what they were getting themselves into, moving into a project. In fact, my father was horrified by moving into a cookie-cutter apartment. He thought it was the urban equivalent of tract housing. It wasn’t bohemian enough. But how could they know the overblown cultural symbolism the word “project” would take on over the course of the next generation? Now, partly because of the success of rap music, it’s become a certain badge of honor.

Lethem: Another generational difference is the enormous advance in Jewish assimilation in the years between Phillip’s childhood years and ours.

Conley: I totally agree. I didn’t even think about being Jewish until I went to California and I realized that I was in a stigmatized group. And then I reread my past. I literally read my high school yearbook and realized, “My god! All these people are Jewish!” Andy Epstein, who was tall and blond and blue-eyed and good looking — I would have never guessed that [he was] Jewish. I didn’t even think, “Epstein, of course he’s Jewish.”

That’s something new to our generation. The other kids, they probably thought I wasn’t Jewish. And the kids that I thought weren’t Jewish because they also had Irish names, they were Jewish too.

Lopate: You know, I want to talk about the issues of writing about this stuff, because I think we can only go so far with sociology, even though we have a sociologist here. I think that it’s still something that takes a certain courage to write about. It feels like a minefield. It feels dangerous. At least it did to me when I wrote “The Countess’s Tutor.” I felt like, “I’m going to get in trouble, but I’m just going to put this stuff out.”

I think one reason Dalton’s book is a triumph is that he does so well with the Dalton character. But every once in a while I would feel like you were trying too hard to understand. That is, I would feel that you were trying to explain that whites still had the power, so there were very good reasons for blacks to be responding in this way. Sometimes I would be grateful for those passages; I would think, “Well, he’s trying to get at a larger understanding.” And sometimes I would be not grateful for them and think, “Well, this is mucking up the prose.”

Conley: You’ve put your finger on one of the most difficult parts of writing a thematic memoir, which is not, like “The Liars’ Club,” so individualized. I’m trying to speak to larger issues. And it was a tightrope to walk. I can’t tell you how many more explanations I crossed out at the last minute. Now sometimes there are a couple of things I wish I did say, because it’s such a sensitive issue, and almost presumptuous for me to write, as a white guy. In some instances I violated the cardinal rule of “show, don’t tell.” Sometimes I put a sentence here or there that would nudge the reader in the right direction. But I hope those were far and few between.

Lopate: They were. It’s a near-perfect book. Really. But there’s a kind of cover-your-ass statement that we all know about, you know, like “Oh my god, I don’t want them to think that I’m a racist because this black kid beat the shit out of me.” But, you know, maybe at that moment you were a racist. And I felt like there was possibly even a certain anger that you weren’t putting in.

I feel that in nonfiction we have to tell as well as show. But it’s a question really of the kind of telling, and how to get a perspective which doesn’t feel like damage control.

Lethem: Damage control’s a great word for it. When you add race to those pure childhood experiences of fear or violence you create a confusion that has no good name. And so you’re afraid the only name for it is racism. To open your mouth at all is to make a mistake.

Lopate: I think it has to do with the Other, on the deepest possible level — that moment when the Other appears to us as nonhuman, or certainly not as fully human as we experience ourselves to be. And whether that’s the way a man feels about a woman, or whether that’s the way a white feels about a black or a black feels about a white, it is this issue of otherness. And I think that part of what political correctness has made us do is to jump and flinch. And what I’d like to see is just a little bit more sitting in the mud of confusion and saying, “You’re absolutely right. We all are fully complex human beings, but let’s not exaggerate our ability to be compassionate with everybody. Let’s recognize how hard compassion really is. Let’s not oversimplify.” You look like you want to disagree.

Conley: I don’t want to disagree with your assessment. I wonder, though, about the way it actually plays out in the sort of constant verbal abuse and constant jostling for position — how many roaches you had in your apartment, how old and dirty your sneakers were, whether your mom was a whore. There are things that would be so easy to say when anger is boiling. How does a kid who’s 9 already know that he can’t say something about how black the other kid is, if you’re white?

It’s always the sensitive issues that can’t be named. I don’t think it’s anything particular to race. If a kid is fat, kids will say so, immediately. Nothing’s stopping them. But picking on somebody about race or about class — even among young kids they’re already socialized that you never do this. If it was only being fat or being tall or short, a physical characteristic, we wouldn’t be so scared to say it. We could say, “Your mother’s so dark.” And then the person would just come back with, “Your mother’s so pale.” Somehow racism is different.

Lopate: I agree that racism is fundamental and important. What I’m really talking about is not what it’s like to be a kid, but our job as writers. And how do we touch explosive material without hedging too much?

Lethem: I want to throw your question back to you, Phillip. In writing that essay, do you feel that you unearthed anger in yourself?

Lopate: Well, I think I’ve certainly got fear. But you know, when I wrote “The Countess’s Tutor,” I was just as nervous saying that the woman I called the Countess was fat. When I described the kid who beat up my brother and compared him to a panther, I thought, “This is going to get me in trouble, this is stupid, don’t do this.” And I thought, “Well, but at that moment, the physicality is what impressed me.” And so this is the question: How do you describe people, knowing that you’re not going to take them on fully and walk in their shoes?

In Dalton’s book, there are clearly people whom he’s going to treat as basically loose cannons, who are totally scary — like the kid who put the knife to your head — and who are not really entered into that much. And then there are the friends, who are given much more reality. It’s funny, this may seem unfair to say, but in a way you’ve benefited from one of your friends being shot and paralyzed. It gave an arc to the story.

Lethem: This is interesting, because the writer’s guilt at using life stories is recapitulated, in this case, in the white kid’s guilt at surviving experiences which the black kid couldn’t. He ends up in jail for them; the white kid ends up in college in California. So similar to that “getting away with it,” which can be an aspect of the writer’s experience. “Oh, we’re all traumatized, but I’m the one who’s got the material afterwards.”

Conley: In some ways I still feel probably more racist than somebody who grew up in lily-white Indiana or somewhere. I tell a story in the book about how in Pennsylvania, where we went for the summer, my sister had a sleepover, and a girl told a ghost story about “the big nigger in the woods” with a complete lack of self-consciousness, just like a story about Bigfoot. In certain ways that’s more innocent, and less racist than I’m capable of being in my head at certain times because of my intimate knowledge of surviving these invisible racial and class wars on a daily basis for my entire childhood.

It’s sort of like being a spy — although I wasn’t a very good one because of my skin color. Your allegiances are compromised. Your knowledge of the “enemy” or the Other is so intimate that you become confused about where you’re coming from and what you feel.

Lopate: You asked me if I was still angry, and I think the answer that immediately came to mind was that most of the anger was at myself. And I think part of what happens when you cross those lines is that you end up internalizing both groups and you can’t help but take it out on yourself.

Conley: I take it out on others, in my head at least. I feel like when I’m with whites, I get so angry and so bitter, as if I practically identify myself as the secret black. Then, when I’m in an African-American or a Latino community, I still can’t resist the behavioral explanations of poverty. Like, look at my old neighborhood. It’s still got garbage and graffiti over it. People don’t clean it up themselves; it’s their own fault. I start getting angry and conservative and sounding worse than George Bush. If you averaged those two, I’m probably average, in terms of my racial attitude. But they’re really nowhere in the middle. They’re very extreme.

What the experience gave me was not any hard insight, but more emotionality about it. I’ve devoted my entire career to these issues because I’m still trying to figure out these contradictory emotions in some rational or scientific manner through sociology — as if I’m going to uncover the magic bullet, though I know I’m not.

Lethem: The book becomes an argument for literature as the only method for dealing with the experience.

Lopate: Yeah, but there are so many bad memoirs. It’s unusual to be able to laugh at oneself and have a sense of perspective, even if you haven’t solved the confusion. The chances of creating literature are very small.

Listening to you, I still think I get angry at myself, and I think the reason is partly a kind of self-distrust that comes from having been too many people. I can no longer trust that I am one thing and one person. I’ve created a chameleon personality that can actually get along with almost everybody. But I guess in some ways I see myself as an actor. That’s the training you get on the streets.

Lethem: Sure. By the time I got to college I could already tell that I was more a chameleon than any of the upper-middle-class or middle-class kids around me. I could haul out the ghetto moves for their entertainment, but I knew I was playing. I could also slide into their social context, but I knew I was playing at that.

Conley: I still feel totally uncomfortable in a white working-class context. Probably there’s where I feel the least comfortable, and next would be a minority context of any class. I’m most comfortable, increasingly comfortable, in white intelligentsia. But I think it’s related to a feeling of a lack of authenticity that is perhaps common to all writers, or to all people who are trying to spin reality.

Lethem: Among writers or academics you can look through anyone’s mask and know that it’s constructed. You know, as you become credentialized, as you publish a few things, you realize, “Oh, we’ve all manufactured this identity. No one was born to it. So here’s where I can be as natural, at least, as everyone else in the room.”