It's probably pointless to ask why Gus Van Sant -- who fought for years to get to direct a shot-by-shot re-creation of "Psycho" -- would borrow so heavily from his own "Good Will Hunting" in his new film; originality isn't his bag. Perhaps Van Sant sees "Finding Forrester" as a potentially lucrative return to the successful formula of "Good Will Hunting," or maybe, to take a less cynical view, he's got a thing for stories about fatherless boys yearning to be mentored by older men. Even the quixotic "Psycho" project fits that psychological profile in a way -- though God help the child who picks Alfred Hitchcock to be his Good Daddy.

"Good Will Hunting" was a handsome, well-textured film that mostly steered clear of shameless heartstring-wringing; "Finding Forrester," by contrast, is a farrago, with a few morsels of deft social observation and likable performances floating around in a conventional stew of overblown, bogus emotion and rigged catharsis.

It's the story of a secretive genius, Jamal Wallace (well-played by newcomer Rob Brown), an African-American 16-year-old who conceals a love for books and an impressive self-acquired education in order to fit in with the rest of the basketball-mad kids in his Bronx neighborhood.

Jamal is also a wizard at the hoops. ("Basketball is how he gets his acceptance," a teacher explains for the benefit of any halfwits in the audience.) When he tips his academic hand by scoring big on a state-administered aptitude test, an elite prep school comes calling with the offer of a scholarship.

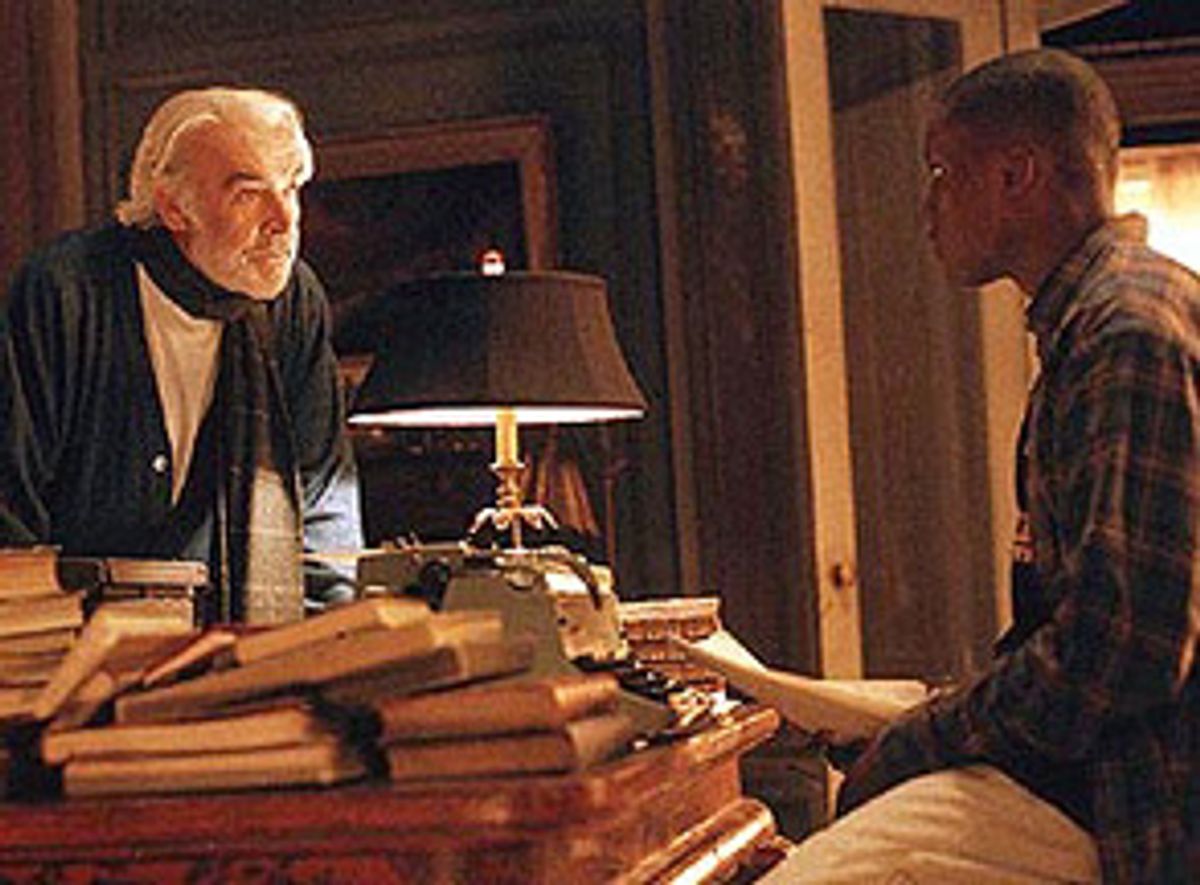

Around the same time, Jamal's journals fall into the hands of a neighborhood recluse (Sean Connery). The old man tosses the books out his window, but only after he's marked them up with a red pencil. Jamal gets the idea that here, at last, is the teacher he craves. A prickly friendship ensues.

Meanwhile, back at the prep school, there's a love interest in the form of Claire (Anna Paquin), a wry Upper East Side princess. We're also given an oreo on the basketball team, who rebuffs Jamal's brotherly overtures ("You think we're the same, but we're not," the kid says, just in case those halfwits need another expository boost), and F. Murray Abraham, chewing up the mahogany-paneled scenery as the supercilious Professor Crawford, a tyrant who believes that Jamal can't possible have written the papers he hands in.

The school's basketball team finally starts winning, and Jamal discovers that his crusty new pal is none other than William Forrester, a Salingeresque writer who won the Pulitzer Prize for his first and only book ("the great 20th century novel," Professor Crawford calls it) 30 years ago and hasn't been heard from since.

Unless you're bothered by minor questions like why a prep-school teacher is called "professor," "Finding Forrester" remains, up to this point, palatable and occasionally interesting. Jamal's dilemma -- how to reap the fruits of his tentative entree into privilege without pulling away from his beloved friends, family and neighborhood -- is both painful and believable, and newcomer Brown plays him as winningly low-key. Van Sant has a sensitive eye, and in a couple of understated scenes (in a subway car, in a classroom), he conveys something of what it feels like to be the only black person in a crowd of whites. The supporting players, particularly Paquin and rap star Busta Rhymes as Jamal's jokester brother, are mostly charming.

Alas, a delicate unfolding of the experience of being stuck between two cultures, and nuanced characters who act and behave like real human beings, are not on the menu for "Finding Forrester." The Hollywood feel-good imperative demands that Van Sant and screenwriter Mike Rich tart up the undramatic life of the writing student with gobs of oleaginous sentimentality and at least one race against time culminating in a grand, life- and love-affirming speech. In the process, they hopelessly mangle Jamal's story. Forrester is given a Tragic Secret -- revealed on the pitcher's mound at Yankee Stadium, no less -- as explanation for his unsociability, and a profoundly confused series of improbabilities conspire to force the elder writer out of his shell to publicly denounce the snooty Crawford and save his young friend from expulsion.

Of course, just as "Good Will Hunting" wasn't really about mathematics, "Finding Forrester" isn't really about writing. Neither film seems interested in the nature of intellectual or creative passion, the particular joy to be found in what's essentially a solitary, internal quest, or the fact that genius is often accompanied by an alarmingly cold-blooded willingness to sacrifice personal relationships in pursuit of its fulfillment. Still, "Good Will Hunting" made some attempt to accurately depict the nuts and bolts of a working mathematician's life. (Ben Affleck and Matt Damon consulted with mathematicians while writing the screenplay.)

That's far from the case with "Finding Forrester." About halfway through the film, Forrester reveals with a wise chuckle the source of Professor Crawford's bitterness: The teacher once wrote a book that was in part about Forrester. Forrester considered the work "stupid" and consequently schemed to prevent its publication. Such skullduggery does happen in the book world, but writers and editors still have enough of a sense of honor to be shocked by it. In the film, Forrester's action is treated as a judicious use of the novelist's clout, instead of a cruel, censorious abuse of it.

The climax of the movie hinges -- interestingly enough, given Van Sant's own preoccupations and the way this film adapts several elements from "Good Will Hunting" -- on a question of originality; Jamal is accused of plagiarizing an old essay of Forrester's and entering it as his own work in a school writing competition. Through a tortuously contrived and nonsensical series of events, Jamal's essay is in fact both borrowed from Forrester's and, at the same time, as one school official acknowledges, "actually quite original in content."

We're asked to believe that Jamal would be absolved if he could only reveal that he knows Forrester and that Forrester invited him to riff on the essay, something the boy can't do without violating his promise to keep the novelist's whereabouts a secret.

But either Jamal presented Forrester's work as his own or he didn't; the friendship isn't really relevant. It's pathetically obvious that this scandal has been concocted by filmmakers in desperate need of some way to force Forrester out of his apartment. Did I mention that in the middle of all this there's a championship basketball game at Madison Square Garden, and that Jamal's future with the school hangs on winning it as well as on defending himself against the plagiarism charge? It's enough to make Will Hunting's head spin.

So much of "Finding Forrester," from its Gordian knot of a story line to the snappy but extraneous basketball court sequences, seems like a frantic attempt to rescue the movie from its uncinematic subject matter. We never learn what, exactly, it is that Jamal writes -- fiction? essays? memoir? poetry? -- or for that matter whether Forrester himself is still doing much work. (There is a final clue, but it's ambiguous.) The movie is hellbent on getting the author out of the house and, by extension, away from his typewriter. That's just another way of saying that writers would be warm, loyal and otherwise terrific people -- if only they'd quit writing.

Shares