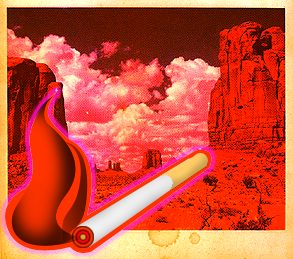

Against the backdrop of wind-eroded red rocks in the desert outskirts of Moab, Utah, a bus the size of a jet airliner pulls to a stop in a cloud of dust. Eighteen members of the Marlboro Adventure Team and an entourage of foreign journalists step off the bus. The journalists are here to cover the company’s month-long, all-expenses-paid outdoors vacation in which four teams of handpicked participants will raft the Colorado River rapids, power their way up sand dunes by jeep and race across the desert on motorcycles and ATV’s in the name of high-powered adrenaline adventure — footage from which will be broadcast overseas in Marlboro ad campaigns and as promotion for the next year’s event.

In response to its rigorous international promotion campaign aimed at young adults, Philip Morris claims to receive nearly 1 million adventure team applications worldwide for its annual desert event. After conducting telephone interviews and a boot-camp selection process meant to measure charisma and athletic ability, the cigarette maker whittles its final choices down to 100 men and women aged 18 to 25 — most of them nonsmokers — who come from countries with the highest smoking rates in the world.

To welcome them to Marlboro Country, motorcyclists do doughnuts in the sand while Marlboro jeeps toot their horns and rev their engines. Cowboys on horseback whoop and holler with their packs of dogs yipping underneath. A camera crew pans in for close-ups of the team members, whose eyes are pinched shut from the sunlight. Someone announces the cameras are rolling, and a flood of questions shoots through the hot air.

“How does it feel to be in Marlboro Country?”

“Are you ready for adventure, the thrill of a lifetime?”

“Is this what you dreamed of?”

Moab has more than 5,000 miles of off-road trails. Mining companies carved many of them in the 1950s to reach pockets of uranium. The trails wind through sandstone cliffs and sand washes hidden by salt cedar scrub bush and pinyon. When the mineral boom went bust, a different industry took over. Today, Moab and its rocky environs are a top destination for outdoor recreation. The town hosts millions of visitors annually — cyclists, climbers and ATV enthusiasts among others. Its chic center, a modest strip of shops just a couple of miles long, offers all the tourist amenities from art galleries to smoothie outposts.

For at least a century, policymakers looked at logging, grazing and mining as the best means for turning a profit on America’s natural resources. Now it’s the land itself that’s the cash cow. Big companies like Philip Morris are part of that process, taking their products to the outdoors and roping us into their scheme through a kind of subliminal seduction of the way we see nature.

Philip Morris, for example, would have you believe the West is about a man on a horse roping cattle and taking cigarette breaks against the view of a snowcapped peak. It’s an association that the company drills into its team members (and those who watch the footage in ads back home) as they experience the American outdoors — as presented by Marlboro. The links between nature and cigarettes, and between the outdoors and Marlboro-sponsored adventure sports, are cemented as the landscape becomes merely a backdrop for smoking and desert toys.

“The Monkey Wrench Gang” author Edward Abbey saw this coming more than a quarter-century ago. He called it “industrial recreation” and used the term to refer to the deliberate selling out of landscape for profit. It goes by other names today: “wreckreation” or “ecotainment.” To some degree, the new use results in higher wear and tear on the land; it also helps to change the way we imagine public space, and potentially the way we experience it.

I asked a Bureau of Land Management staff person if he thought there was something illogical about a branch of the federal government issuing Philip Morris a public land use permit under the pretense of outdoor adventure, given the laws against tobacco advertising in the U.S. Technically, of course, the company isn’t breaking any laws. As long as no Americans take part in the event and as long as the event originates outside U.S. borders and Philip Morris is careful not to display the traditional red, white and black Marlboro jeep in the desert, they’re off the hook. But even given the murky legalities of Marlboro’s ad scheme, should we be using public lands to sell products?

“What makes the presence of Philip Morris out here any different than Budweiser promoting the Olympics?” the BLM staffer replied. “Isn’t that what America is all about?”

His response may have been facetious, but according to Jim Lyons, former undersecretary for natural resources and environment, the staffer is right. Lyons said as much in a speech to the American Recreation Coalition’s Great Outdoors Week when he declared: “We can make the national forest the Microsoft of outdoor recreation. We’ve got a great product to sell. And, with your help, we can make it even better!”

The product is selling. In 2003, a bicentennial celebration of the Lewis and Clark Expedition will see more than 25 million people following in the explorers’ footsteps by car, bike, foot or boat in three yearlong events. The Great Western Trail, a pathway of trails from Canada to Mexico, is also up for review. It’s designed to lure international tourists to the West and to “hone and utilize our wide open spaces, our cowboys and Indians lore, our rivers and mountains.” The Wild Wilderness organization, an environmental watchdog group in Bend, Ore., also refers its Web site readers to additional plans for theme parks, tramways and walkways through wilderness areas.

Scott Silver, executive director of Wild Wilderness, agrees that outdoor recreation, if managed well, presents people with a better use of open space than the nearly bygone days of mining and timber extraction. What he and others fear, however, is the tendency for commercial enterprise to be the primary voice in open-land policy.

“We can be fairly confident that the policymakers will manage the land as they have managed every other extractive use on public lands: for the benefit of corporations and to the detriment of the public and the land itself,” he says.

Indeed, plans like the Lewis and Clark bicentennial invite a new consumer infrastructure. Where, after all, are the thousands of Lewis and Clark enthusiasts going to sleep? Eat? Buy gas?

One possible solution is the Recreational Fee Development Program (RFDP) being tested in 100 sites around the country. These sites are charging anywhere from $3 and up, depending on the type of activity and number of people, to recreate on public lands. Proponents say the fee program will help shore up funds that have fallen short over years of federal mismanagement. Environmentalists view it as a dangerous step in the wrong direction, a plan that favors industrial recreation interests over anyone who still might hope to view nature the old-fashioned way, with a backpack and frying pan.

On the surface, the RFDP seems a logical enough way to collect funds to better manage land trusts. The very idea, however, of raising funds for public land implies that some sort of commercial infrastructure is needed to make the land “viable.” Environmentalists ask what happens when, in a profit-driven system that works harder to generate cash than to protect lands, the boat- and ATV-lovers offer to pay more for a wilderness permit than a fisherman or backpacker.

As the Bush administration and new land-use policies threaten to bring more big business outdoors, it means companies like Philip Morris and other for-profit interests will increasingly help dictate public-land-use policies. It means that a remote lake in the backcountry will soon carry a price tag. It signals the end of recreating on public lands and enjoying nature on an “as is” basis.

Two final products come out of Moab’s Marlboro Adventure. After dinner, on the final evening in the desert, team members approach the stage to receive diplomas for their achievement in conquering the wild. Journalists covering the event are given a collection of the week’s finest images on CD. Meanwhile, the Philip Morris ad team brings us one step closer to taming the Wild West, to reducing the frontier into a computer-enhanced vision of fun and adventure without even the threat of a rattlesnake bite.