Sometimes called the conservative prom, the American Enterprise Institute’s Francis Boyer lecture and dinner is an annual black-tie event that brings together many classes of right-side Washington: ideologues, intellectuals, bureaucrats, research assistants, foundation heads, journalists — and a fair sprinkling of people who actually pay for the privilege of dining with them. An award is given; the recipient delivers a lecture. Things kick off with free drinks, include a solid meal and feature first-rate live music. It’s a terrific evening, a grand departure from your average suffocating D.C. cocktail party. I probably should be too embarrassed to admit it, but the conservative prom is the reason I own a tuxedo.

And this year was even more special than usual. Our guy is in the White House, and that has a most direct effect on everyone there. To take an obvious example, Lynne Cheney, an AEI fellow, is married to the vice president — you know, Dick (the 1993 Boyer award winner). Both were there, along with a retinue of Secret Service agents. But there were also many young politicos whom I knew from dollar-Bud happy hours, now doing things like setting up departments of the executive branch. Instead of a gathering of dissidents, this year’s dinner and lecture was, suddenly, a party for the in-crowd

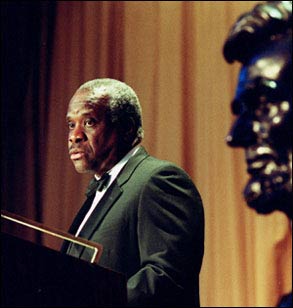

As such, it was the most exuberant expression of Washington right-wingery I have seen. The centerpiece of the evening was a lecture by this year’s Boyer winner, Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas — a wild, high-speed pitch aimed at the heart of American political debate. It was truly something to behold. In a roomful of conservatives, Thomas proved more conservative than the vast majority. In a roomful of outspoken people, he seemed the boldest. Watching him, I felt my spine tingle and my head spin. This was not necessarily a good thing.

In his speech, Justice Thomas ran the bases of conservative thought. He described coming to Washington in 1979 and being on the incorrect side of debates over affirmative action, welfare and school busing. “When whites questioned the conventional wisdom on these issues, it was considered bad form,” Thomas said. “When blacks did so, it was treason.” Fighting words followed fighting words. “It takes no education and no great intellect to know that it is best for children to be raised in two-parent families.” We Americans, he said, are embroiled in a culture war.

Even his words of praise carried the distinct echo of a man so firmly on the right side of the ideological scale that it would take an editor for the New York Review of Books (or two) to balance him out. He praised conservative intellectuals with the fervor of a conservative college student discovering them for the first time: “It is awe-inspiring to read the works of Gertrude Himmelfarb, Michael Novak, Michael Ledeen, Judge Bork and others in this audience.” Thomas wasn’t just playing the room. In September 1975, when the Wall Street Journal published a review of a book by Thomas Sowell (1990 Boyer recipient) by AEI scholar and Catholic intellectual Novak (1999 Boyer recipient), Thomas said, “The opening paragraph changed my life.”

The beleaguered justice alluded to his own ugly confirmation hearings as a way of talking about the price one pays for showing political courage. He even seemed to take a shot at President Bush and his notion of “compassionate conservatism.” He denigrated the importance of civility in politics, making use of Himmelfarb’s distinction between caring and vigorous virtues. Compassion is among the former, he said, and serves only to “make daily life pleasant.” Courage, however, is among the latter. Vigorous virtues, Thomas quoted Himmelfarb, “characterize great leaders, although not necessarily good friends.”

Surely it was a kind of courage that gave Thomas the strength to praise Pope John Paul II, repeating the pope’s advice to people with strongly held convictions: “Be not afraid.” But it could only have been a kind of mania for revealing one’s thoughts that led Thomas to use the pope’s words to describe our “culture of death.” This phrase, of course, is papal shorthand for capital punishment, abortion and euthanasia — the opposite of John Paul II’s “gospel of life.” Summarizing, Thomas said, “Listen to the truths that lie within your heart, and be not afraid to follow them wherever they may lead you.”

But if you ask me, many of the truths, especially the really conservative ones, that lie within Justice Thomas’ heart should stay there. It seems the opposite of wisdom for a sitting Supreme Court justice to trumpet his privately held views on controversial questions of domestic policy. It may be courageous for a man so openly scorned by so many Americans to invite yet more scorn. I do admire that. There is a kind of balls-out, happy-warrior outrageousness to it that makes me want to stand up and shout “Bravo!” And were Thomas simply an officeholder whose enemies were free to take their revenge at the polls, I’d be calling him the bravest man in American politics.

But Thomas is a member of the Supreme Court, and that institution is likely to share in what scorn he inspires. His views on the culture of death are easy fodder for critics should Roe vs. Wade be revisited (or, for that matter, cases involving the death penalty or euthanasia). His public musings on preferential treatment in college admissions could be used by his enemies to denigrate the high court’s decisions on affirmative action.

Watching him speak the other night, I found it easy to see the qualities that have made him a conservative hero, only I now find myself wishing he didn’t show them to the whole world. I had always rejected the liberal smear that called him stupid for not taking part, with the other justices, in the interrogation of lawyers who bring cases before the court. But now, here he was, the famously silent jurist, opening his mouth to articulate an indiscriminate passion for the conservative movement. He denounced political orthodoxy, but he personified conformity to the fire and brimstone branch of conservatism. My impression wasn’t of a great mind speaking to a room of movement types; here was a movement type speaking to his own.

Before the evening closed, I made the rounds, saying hello to friends, congratulating many on their well-deserved fortunes. Being at a party like this is a bit like walking through a group portrait of the vast right-wing conspiracy. I get a real jolt of pleasure from that, hanging around some of the major characters and great bit players of history. I mean, how’s this for a great Washington moment? I saw Kenneth Starr with his arm around Clarence Thomas, the two of them yukking it up like a pair of old college buddies. Actually, one can hardly imagine a better picture of moral courage — or a better pinup for liberal outrage.