Before it vanished from the Internet earlier this month (as popular Web sites are prone to do), one particular Oliver Stone home page featured a photo of the controversial filmmaker beneath a large red headline that read: “Oliver Stone: Writer, Director, Thinker.”

This type of hyperbolic puffery is not uncommon on the Internet, especially among diehard movie fans who delight in devoting enormous chunks of time and bandwidth to deifying their cultural idols. What distinguished this gush-fest from the others, however, was that the site — OliverStone.com — was the director’s own Internet boutique, a Web-chapel of self-devotion where Stone offered commentary on his movies and the film industry in general, and also dumped samples of his writing, merchandise and, as always, a blizzard of opinions on everything from the Vietnam War and the JFK assassination to being misunderstood by the media and the true nature of evil.

That’s a lot of self-promotion, even for man doing triple-duty as a writer, director and thinker.

Then again, it is this very Ptolemaic view of the world — in which the universe revolves around him and his movies — that makes Oliver Stone one of the more compelling, analyzed and, to some, important directors in American cinema. Because he chooses to make films about real-life subjects and events — often to the chagrin of historians and scholars who like to challenge his accuracy — it is a given that when a Stone movie opens, it will have an agenda that goes beyond simply chasing the Gibsons and Grinches to the top of the weekend grosses heap.

True, in the case of Stone’s work, those agendas can be maddening and misguided — witness the general public outrage over his gratuitous 1994 gore orgy, “Natural Born Killers.” But in Hollywood’s ongoing battle between the usually profitless think picture and the enormously successful dumb-and-dumber formula, Stone has staked out a comfortable middle ground with a body of work that attempts to educate — sometimes enlightening moviegoers, other times haranguing them — even as it entertains.

“Oliver Stone’s place in motion pictures is yet to be decided,” writes Michael Singer in “Etched in Stone: The Films of Oliver Stone,” “but this much is sure: He is in love with the primal, even terrifying, power of film, and he’s been completely unafraid to harness that energy and unleash it with explosive impact on cinematic, social and political landscapes.”

But as more filmmakers begin painting on nonfiction canvases both large and small (from “Erin Brockovich” to “Thirteen Days”), Stone may find his role as Hollywood’s leading moviemaker-historian and unrepentant boat-rocker eliciting more yawns than gasps.

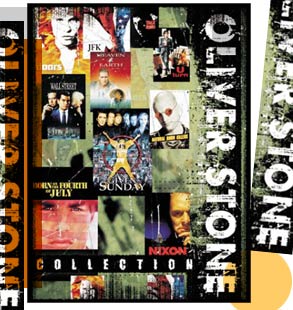

Scanning the 10 titles in the new Warner Bros. DVD box set of Oliver Stone movies made between the years 1987 and 1999, you can’t help but note that Stone’s trajectory over the last 15 years has been a curious one. His popularity at the box office continues on an even keel even as his stock in trade — overturning historical and cultural rocks to reveal the creepy crawling universes beneath our national institutions — loses its jolt.

For example, while many critics yowled at the artistic and factual liberties Stone took in decrying the Warren Commission Report in his 1991 Kennedy assassination exposé, “JFK,” most simply shrugged eight years later when he pulled back the curtain on similar intrigue and corruption in the locker rooms and front offices of professional football (“Any Given Sunday”). Either America has gotten less interesting in the past decade, this phenomenon suggests, or it is no longer rattled by its own lapses. (The Clinton administration, all by itself, dispels the former notion while handily supporting the latter.)

To be fair, Stone is not entirely responsible for the relative ennui his recent films seem to provoke. After all, he is now peddling to an entertainment culture that finds “The NewsHour With Jim Lehrer” slotted opposite “Extra!” and “Access Hollywood,” and prime time dominated by programs like “Temptation Island” and “Survivor” — freak shows that seek to normalize the very kind of human ugliness that an Oliver Stone movie normally takes two or three hours to uncover.

Still, one has to wonder if Stone’s varying degrees of success and failure over the years have been a result of his selection of material, the temperament of the country at the time of the films’ releases, or perhaps a little of both.

Strangely, the DVD box set does not include the movie that put Oliver Stone on the map. By the time he wrote and directed “Platoon” (1986), Stone had labored as a screenwriter in the film industry for more than a decade, with credits on films like “Midnight Express” (for which he won an Oscar), “Conan the Barbarian” (1982), “Scarface” (1983) and “Year of the Dragon” (1985). But it was his unapologetic, first-person portrait of a young G.I. in Vietnam — based on his own tours of duty there between 1965 and 1968 — that captured the true brutality of the war. The film won him a new following as well as a tentative slot in the dependable rotation of auterists’ favorite working American directors of that time — Steven Spielberg, Martin Scorsese, Francis Ford Coppola, Robert Altman and Woody Allen.

The “Stone Collection” does, however, include “Born on the Fourth of July” and “Heaven and Earth,” the second and third installments of the director’s Vietnam trilogy, both of which still resonate. (Both DVDs, like all of the films in the box set except for “U-Turn” and “Talk Radio,” feature full-length director commentaries. “JFK,” “Nixon,” “The Doors” and “Any Given Sunday” also include bonus discs filled with extras like deleted scenes, making-of documentaries and, in the case of “Sunday,” screen tests and a gag reel.)

“Born on the Fourth of July” (1989) was not the first film to explore the emotional and physical trauma suffered by soldiers returning stateside from Vietnam; “Coming Home” and “The Deer Hunter” had both examined the subject with candor and sensitivity. But what Stone’s movie offered that the others didn’t was a real-life hero, Ron Kovic, whose passionate memoir served as the basis for the film. Kovic’s character (portrayed with painful honesty by Tom Cruise, much of the time confined to a wheelchair) remains a documented casualty of the war, not merely a collage or interpretation (à la Charlie Sheen’s character in “Platoon”) that critics could brush aside as another example of Stone over-reaching.

Similarly, “Heaven and Earth” (1993) draws from the autobiography of Le Ly Hayslip, a Vietnamese woman whose life story charts a cyclical course from the serene, pre-war countryside of her homeland to the mayhem of the Viet Cong insurgence to her enlightening return to the tenets of Buddhism in the aftermath of the war. Overlooked and underappreciated by moviegoers and critics, “Heaven and Earth” remains a beautiful and touching film and, on a personal level, one of Stone’s favorites.

Two Stone efforts in the collection attempt pointed social commentaries that, for different reasons, have become blunted — even caricatured — with time. “Wall Street” (1987) is the tale of a hotshot broker (Charlie Sheen) and his ruthless mogul mentor (Michael Douglas) who bathe in the excesses of the 1980s, recklessly engaging in insider trading. But because the release of this slick parable was sandwiched between the real-life dramas of Ivan Boesky and Michael Milken — and because those scandals were more spectacular than any movie could depict them — the film was ultimately less an investigative white paper than flash paper. Indeed, over the years it has become better remembered for the charismatic performances of its leads (Douglas won an Oscar for his turn as the evil Gordon Gekko) than for any trenchant thesis it makes about the fiscal friskiness of the modern marketplace.

Likewise, “Natural Born Killers” (1994), a bullet-ridden chronicle of a modern-day Bonnie and Clyde (played by Woody Harrelson and Juliette Lewis), aimed its double barrels at two of America’s more embarrassing obsessions — violence and tabloid TV. Yet in making his point, Stone loaded up the film with such generous doses of voyeuristic carnage that he ended up perpetrating the very offense he sought to illuminate. The critics called him on it. So did the public.

Then there’s “The Doors” (1991), Stone’s elegiac tribute to rock star Jim Morrison. Written and filmed as a kind of travelogue of the 1960s — a Baedeker to the twin ages of Aquarius and substance abuse — it ultimately draws the conclusion that if you drink enough alcohol and do enough drugs, you will die young and become a legend. And that’s about it. Looking back, the movie’s message may have been hamstrung from the start. Obviously keen on depicting Morrison’s short-fused, short-lived career in all its messy glory, Stone sacrificed the opportunity to use the band’s story as one brush stroke in a larger picture, the way he so effectively allowed the Kennedy assassination and Watergate break-in to serve as metaphors for the turbulence of the ’60s and ’70s. Unwittingly, this turned what could have been an otherwise penetrating sociological study into little more than a noisy soap opera.

Which is not to say that “The Doors” doesn’t succeed in its own right. Released the same year as “JFK,” it shares that movie’s meticulous attention to period detail as well as its emotional volatility. Loud, chaotic and drenched in groovy, tie-dyed atmosphere, it boasts a pulsing soundtrack and a star (Val Kilmer) who captured Morrison’s complex and brilliant self-destructiveness.

“The Oliver Stone Collection” also includes “Talk Radio” (1988), adapted from Eric Bogosian’s play about a boorish radio host; “U-Turn” (1997), an uneasy road picture in which Sean Penn plays a gambler stranded in a small Arizona town; “Any Given Sunday” (1999), Stone’s frantic NFL saga starring Al Pacino and Cameron Diaz; and “Oliver Stone’s America,” a documentary that, despite its heady title, amounts to little more than a 50-minute softball interview conducted by filmmaker Charles Kiselyak, who is clearly a Stone devotee.

So what of “JFK” (1991) and “Nixon” (1994), the two films that Stone’s detractors point to as the quintessence of the director’s skewed world view and unchecked paranoia (and, not incidentally, the prize jewels in this box set)? To be sure, neither movie treads lightly on its subject. In “JFK,” Stone proposed nothing less than a global conspiracy behind Kennedy’s murder; in Nixon, he neatly traced the 37th President’s tragically flawed character back to his parochial Quaker boyhood. In both cases, Stone didn’t exactly help his own cause by tinkering with the presentation of the facts — combining events, streamlining chronologies, even fabricating characters (as with the informant “X” in “JFK”) — in an effort to consolidate the movies’ narratives.

But what often gets lost in the din of criticism of “JFK” and “Nixon” is that Stone’s research into his subjects remains as impeccable as it is exhaustive. Time and again pressed by scholars and journalists to support his facts — defending himself, by the way, far more than any film director should be expected to — Stone has repeatedly and consistently shown how his films draw from the record. After “Nixon,” he even published a 600-page book filled with essays, interviews and documentation that support the claims made by his movie. Was Ridley Scott similarly required to defend his interpretation of the gladiator era down to the last dusty sandal? Did historians go lighter on Steven Spielberg after the release of “Saving Private Ryan” because, perhaps, D-Day left a better taste in America’s mouth than an 18-and-a-half-minute gap?

If the most valid criticism of Oliver Stone is that that he constructs his cinematic assaults with the precision, purpose and passionate bias of a district attorney gone mad, what of it? In the end, this is what many filmmakers — from Charlie Chaplin to Spike Lee — have been doing all along, and in most cases, moviegoers have been the better for it.