David Horowitz is having a ball.

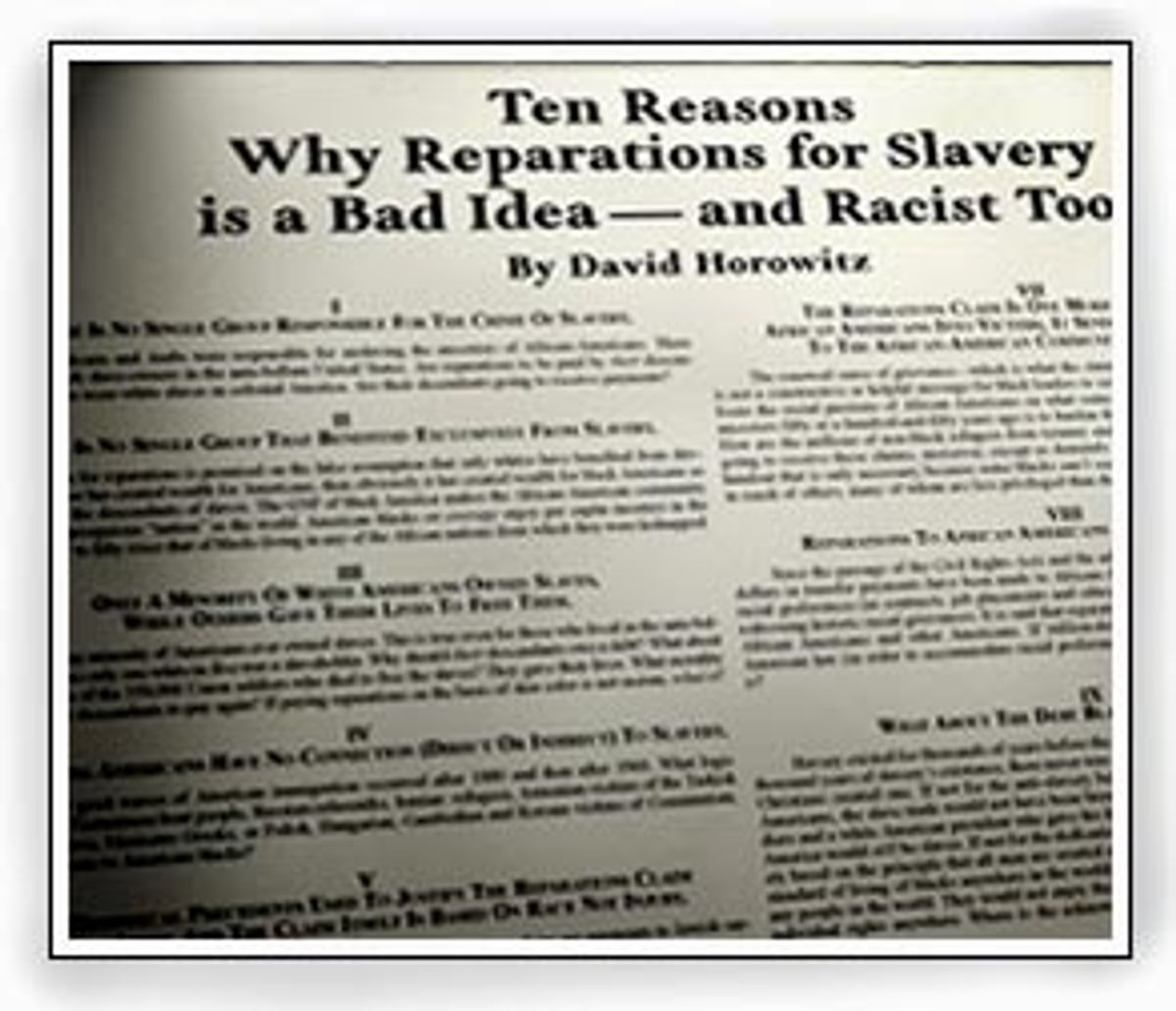

Armed with a modest advertising budget, the conservative provocateur (and Salon columnist) set out to buy ads in college newspapers across the country, attacking the notion of slavery reparations: "Ten reasons why reparations for slavery is a bad idea -- and racist too." But so far at least 10 papers have rejected the ad, editors at three of the four that agreed to run it have since apologized and the result has been a windfall of free publicity for Horowitz and his case against reparations. The San Francisco Chronicle and the Wall Street Journal have come to Horowitz's defense; in the Washington Post, Jonathan Yardley called the attacks on the ad "hogwash," concluding "I have read the ad several times and can find no racism in it."

"Now we're sending the ad to about 100 papers," an excited Horowitz says by cellphone, rushing from meeting to meeting. "We can't afford to place it everywhere, but since most are refusing to run it, we might as well try. Can you believe it? Harvard, Columbia, the University of Virginia all rejected it! I expected a hue and cry, but I never expected this." Horowitz hasn't gotten so much mainstream media attention since Time's Jack White called him a racist.

Are these campus journalists secretly on Horowitz's payroll? Of course not, but they're working for him just the same. The rightist rabble-rouser is running circles around his ideological enemies, making idiots of them, winning thousands in free publicity for every dollar he tried to spend with the campus papers. Meanwhile, activists are taking to the streets again in Berkeley, Calif., and Madison, Wis. -- which might be a welcome sign of life on the mostly dormant campus left if their cause wasn't so insufferably self-destructive.

Lost in the ruckus over the reparations ad is the fact that Salon ran a version of it as Horowitz's biweekly column last June. The column ran at greater length than the ad, and was more carefully edited, perhaps (full disclosure: I edited it, and I'm pretty sure I wrote that catchy headline), but it made essentially the same points. Of his 10 points, most are variations on the argument that forcing Americans to pay for reparations would be unjust, in large part because it would be difficult, if not impossible, to decide exactly who should pay them. Black Africans, brown Arabs as well as white Europeans were involved in the slave trade, while the immigrant ancestors of most white Americans were not. And should whites who are descended from abolitionists and other slavery opponents get an exemption?

We received hundreds of letters about the column, most but not all of them critical. We ran a rejoinder by a regular Salon contributor, Earl Ofari Hutchinson, supporting reparations. We got even more letters, as Horowitz supporters slammed Hutchinson. The debate was lively, arguments on all sides got thoroughly aired, a good time was had by all.

Nobody picketed our offices. Nobody came to Salon with a list of grievances to be addressed. Nobody sought or was given an apology. Nobody called us racist.

Why, then, is Horowitz's ad campaign stirring up such craziness on college campuses? On this point, at least, it's hard to avoid agreeing with my conservative colleague. (And as he knows, I respectfully disagree with him on just about everything.) The Horowitz ad is explosive because for too many years campuses have been places where ideological bullies, usually on the left, have been devoted to blocking political debate, rather than engaging in it -- and they've succeeded.

I've become a conscientious objector in the war over political correctness in American universities. There are more important issues to me, and campus p.c. crackpots are just too easy a target. Besides, it seems overwrought to insist that hotheaded identity-politics power-struggling by self-important, hormone-addled, coming-of-age undergrads (even though it's abetted by doctrinaire professors) is any kind of microcosm for the state of American race relations, politics or civic life.

Plus, in the Horowitz fracas, the campus journalists and activists being interviewed seem overmatched by the adults piling on, and I've been a little reluctant to join the fray. These are students, after all. Poor Daniel Hernandez, editor of the Daily Californian at UC-Berkeley, has become a poster boy for political correctness run amok -- and the crisis in liberal education -- with his apology for having run the Horowitz ad. Jonathan Yardley attacked him for bad grammar -- two split infinitives! -- as well as bad reasoning. As someone who can't resist splitting an infinitive now and then, my heart went out to Hernandez. The executive editor of Foxnews.com, Scott Norvell, took time from his busy day to write a personal e-mail to young Hernandez, attacking his "cowardice and audacity" in apologizing for the ad. "I'm getting letters from journalists all over the country telling me I'll never get a job in journalism again," the editor admits gloomily.

But if the piling on is unseemly, Hernandez brought it on himself. He defends his apology, though he admits he might have put it differently had it not been written in the heat of a clash with campus activists who'd stormed the Daily Cal offices to protest the ad. "It was purposely confrontational," he says of the ad, explaining, "We don't run any ad that's blatantly inflammatory -- that's just our policy." It's probably worth noting that most media outlets reserve the right to reject controversial ads, and regularly do. But it's also worth noting that Horowitz's anti-reparations position is thoroughly mainstream: A Time poll of about 30,000 respondents showed 75 percent were opposed to reparations for slavery.

"Our editorial policy is as open as it can be," Hernandez continues. When I ask if he's ever run an editorial feature as "confrontational" on the question of race as the Horowitz ad, he admits he hasn't.

In the end it's probably condescending to protect these student journalists and activists from themselves, especially when they so desperately need serious intellectual engagement. The reaction to Horowitz's ad proves at least one of the points he makes in it: A morbid attraction to the role of victim, and an unhealthy fear of disagreeable ideas, are all too common in campus politics, and they seem to afflict left-liberal students of color disproportionately.

Horowitz is a provocateur on questions of race, I'll admit. Sending his piece to college newspapers was a provocation (one he justifies by saying it's the only way he could open a discussion of the subject on campuses), and sending it during Black History Month poured more gas on the fire. If Horowitz seems a little unhinged on the subject, the reason may be his painful personal history. Hell hath no fury like a white person who once idealized blacks who's since been disappointed by them. Horowitz, the recovering Negrophile (sorry, there's no modern, polite word for it) often seems to blame the entire race for the admittedly vile outrages of the Black Panthers, who he believes (with convincing evidence) murdered his friend Betty Van Patter.

Just the way he once romanticized black outlaws -- as so many white leftists do, accounting for Panther worship in the '70s and the creepy Mumia cult today -- Horowitz now inflates black leaders' moral and political flaws. And much the way he glorified the long-suffering black community's capacity for both redemption and radicalism, he now exaggerates its problems and pathologies. When he sent the reparations ad out as part of a direct-mail fundraising package, it was accompanied by a letter warning darkly about a couple of recent murders of whites by blacks, which he likes to call "hate crimes," as though it's open season on white folks and our only defense is giving money to his nonprofit. Horowitz is frankly obsessed with blacks, to what seems an unhealthy degree, and as a colleague I've been tempted to ask him to give it a rest.

But while I don't agree with everything in his reparations ad, it is actually one of his more persuasive arguments. Typically, Horowitz overreaches, calling welfare benefits a form of reparations to blacks, even though most welfare recipients are white. But he also makes an excellent point that his detractors refuse to grant: Slavery was a worldwide phenomenon, and Americans deserve some credit for a multiracial movement to end it. And by refusing to acknowledge that complicated history, reparations advocates risk cultivating a sense of alienation, isolation and victimhood among African-Americans that's ultimately self-destructive.

In my reading, the ad is not racist. Provocative, sure. Offensive to some, probably. Unfit to grace the ad pages of a college newspaper? Give me a break.

Of course, like virtually everybody else writing about this mess, I'm a grown-up college journalist myself, and the controversy just happens to be hottest right now at my alma mater, the University of Wisconsin. There, a conservative student newspaper, the Badger Herald, ran the Horowitz ad, and has since been subject to attacks and demonstrations against its "racist propaganda" by student activists. Meanwhile, the official UW paper, the Daily Cardinal -- where I was campus editor in 1978 -- ran an ad purchased by the Multicultural Students Coalition attacking the Horowitz ad. Ironically, the Badger Herald refused the coalition's ad, proving that intellectual intolerance can be found on the right as well as the left. But the Cardinal ran the students' ad "because we felt that as a newspaper it's our position to provide our pages for anybody to purchase," sophomore Eric Storck, the paper's business manager, told the Wisconsin State Journal.

That's my Cardinal, I thought proudly -- still representing the proud tradition of free-speech absolutism. I came of age when the paper was unabashedly left-wing -- it's more centrist now -- and I remember interminable staff meetings devoted to arguing about taking ads from politically incorrect advertisers. But in the end, we always took them. At the time, our free-speech commitment was articulated with a macho lefty swagger: You take the money of advertisers you disagree with, and then you screw them with it, printing stories and editorials decrying whatever cause the advertiser represents.

Alongside an ad from South Africa-based De Beers diamonds, for instance, we ran a long, tortured exposé of conditions for blacks in De Beers' mining camps written by yours truly. We were ham-handed and self-righteous and close-minded in our way, but we were willing to let ideas clash. Certainly we had enemies on the left, who opposed what they saw as our bourgeois free-speech fetish. But I admit we never faced the fashionable multi-culti marauders who descend on college papers and try to punish those who publish anything that offends their sense of racial purity. Though I'd like to think we'd have stood up to them, I really don't know.

But I do know that fearlessness appears to be in short supply among both activists and journalists on campus today. I called Eric Storck at the Cardinal to congratulate him on continuing the paper's free-speech legacy. I asked if he'd been offered the reparations ad yet -- I knew Horowitz was in the process of approaching the Cardinal -- and Storck, a little embarrassed, told me he wouldn't sell Horowitz ad space right now.

"At this point I wouldn't take it. It's clear the message has already gotten on to this campus, and I don't feel the need to rekindle feelings that have already been stirred," he said haltingly.

The Cardinal regularly takes provocative ads, Storck admitted -- it recently accepted an ad from an anti-abortion group that both staff members and community activists argued should have been rejected. Why the different standards for the reparations ad?

"I'm not gonna say we wouldn't have taken it two weeks ago, but with all the protest and everything, now we would not take it," he said.

So the fact that some activists picketed the Badger Herald means that Horowitz won't be able to place his ad?

"Yes. In this specific case, yes. There's anger on campus now. Given the circumstances right now, it would be inappropriate for us to run that ad. With the discussions regarding race on campus, it's just not an appropriate ad. The Multicultural Coalition is very upset."

Horowitz is now calling his detractors "brownshirts," of course, and on the phone he reminds me "the Nazis took over universities first." It's a little overheated. And yet there is something disturbing about the idea that a group of offended students could intimidate student newspapers into rejecting Horowitz's ad, or apologizing for it once they'd accepted it.

Leave it to the left to give Horowitz an issue that gives his take on race and political correctness new life and new credibility. "To be honest, we feel kind of duped by this man," Daniel Hernandez of the Daily Cal admits. "He's gotten more exposure than any ad could have given him. It's kind of embittering."

Indeed it is. But it's an important lesson for Hernandez and his contemporaries. They could have taken Horowitz's money and, if they despised his arguments, screwed him with it, attacking his arguments in the same pages he paid good money to have his words published. By refusing his money, spineless campus journalists are getting screwed by him instead.

Shares