The world of movies that never get a theatrical release is littered with cheapo teen horror pictures and action movies that look as if they cost a dime to shoot. But what does it say when a picture like Rodrigo Garcia's lovingly detailed "Things You Can Tell Just by Looking at Her," which won the first-time writer-director a prize at Cannes last year, doesn't make it to theaters in this country? (The picture makes its debut on Showtime Sunday at 8 p.m.)

"Things You Can Tell" was shown to critics last year, many of whom loved it. John Powers, for one, raved about it in a lead review for Vogue. But MGM/UA decided not to release the picture theatrically. An MGM/UA spokeswoman explained that although the picture is small and "great," the studio felt that it wouldn't be able to draw an audience in theaters and would have a much better chance of being seen on Showtime.

The irony is, she's right -- at least in the way the major studios sell their products, deeming certain pictures unworthy of the time and money it would take to market them. But if a movie like "Things You Can Tell" were properly sold -- for example, opened in art houses or specialty theater chains instead of just dumped into multiplexes, with its prestigious stars emphasized -- there's no reason it couldn't find at least a respectably sized audience. (By comparison, a similarly well-written and -directed picture, Kenneth Lonergan's "You Can Count on Me," gained a great deal of critical respect and audience affection, without any of the star power this movie has. It may not have made a fortune, but then, it didn't cost a fortune to make.)

The small bit of good news is that at last people will have a chance see "Things You Can Tell" for themselves, albeit on a much smaller screen than it deserves. Garcia's debut as a writer and director (the son of writer Gabriel García Márquez, he's well established as a cinematographer, having shot pictures like "Danzon" and "Mi Vida Loca") is one of those finely crafted, intimate pictures that are often characterized, by studio publicists, critics and audiences alike, as "small." It is small, but it also has plenty of weight and heft. It's loaded, like a raindrop.

"Things You Can Tell" consists of five gently interlocking vignettes, all set in Los Angeles' San Fernando Valley, an environment that encompasses cozy, if sprawling, suburbia and coolly efficient office parks, places where loneliness breeds even in bright sun. There are no elaborate plot machinations in "Things You Can Tell." Almost all the action springs directly from the performers; the beautifully conceived script gives them plenty to work with.

The women's stories are discrete elements, overlapping only in subtle ways -- their narratives don't rely on contrivances or coincidences to make them interesting. Dr. Elaine Keener (Glenn Close) is a successful middle-aged physician, the type of person who'll never admit to herself or anyone else that she's lonely; she has been pursuing a recent crush at her workplace, but he won't return her phone calls. Rebecca (Holly Hunter) is a 39-year-old bank manager who discovers she's pregnant by her married lover (Gregory Hines).

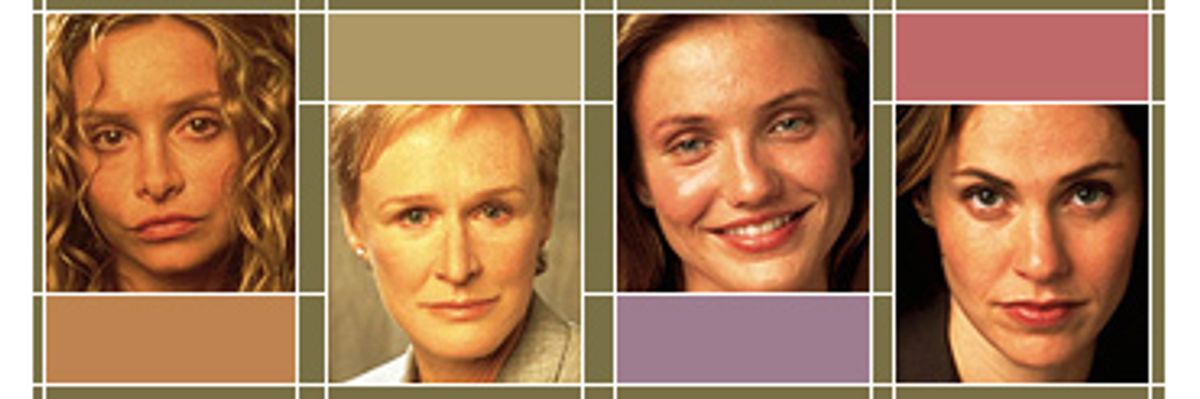

Rose (Kathy Baker), an author of children's books and a divorced mother of a teenage boy, thinks about romance for the first time in years when a handsome, poised, charismatic hospital accountant (Danny Woodburn), who also happens to be a dwarf, moves into the house across the street from hers. Christine (Calista Flockhart), a tarot-card reader, recalls how she and her dying lover (Valeria Golino) got together in the first place, reinforcing the seams of a relationship that the two of them know will soon be severed by death. And Kathy (Amy Brenneman) is a single police detective who dates much less frequently than her alluring and sexually confident sister, Carol (Cameron Diaz), who happens to be blind; Kathy takes the timid step of going out with a colleague (Miguel Sandoval), while Carol deals with her own disappointments, never succumbing to self-pity.

It's crucial to point out here that these aren't just sensitive little fables wrapped around the perennially popular subject of women's feelings, the peculiar manifestations of women's power that are so often dangled in front of men like dainty sticks of dynamite. This is hardly the stuff of those plodding women's dramas you see on the Lifetime network, things that attempt to deal with "real" women and their "real" problems but only end up mixing dishwater dreariness with sugary hopes and dreams to come up with something that feels about as lively as mud.

Garcia keeps these stories moving; they're deftly written and shaded with delicate details, like the way Close's rather businesslike character pauses to admire herself in the mirror, sporting a pair of borrowed diamond earrings. Shot by genius cinematographer Emmanuel Lubezki ("Sleepy Hollow," "Great Expectations"), "Things You Can Tell" looks great, too. Lubezki colors uncertainty and yearning not in the typical palette of blues and grays but in the soft glow of sunlight and the brightness of concrete and gleaming cars. He makes the neatly kept pastel suburban houses lined up on Kathy Baker's street look like dream cottages out of a middle-class fairy tale.

"Things You Can Tell" is right in so many little ways that it's hard to describe the final effect. For one thing, it doesn't go out of its way to portray people with disabilities sensitively and realistically, and that means that in the end they come off more like real people than token characters. There's no question in your mind that a nervously graceful suburban mom like Kathy Baker would want to sleep with Danny Woodburn's dwarf accountant, whose self-assurance, kindness and sexual confidence are so well defined.

And every actress glows here. That's partly owing to their innate talent, but judging from the finished product, Garcia also seems to have a knack for shaping actors' performances. More than anything, I got the sense that these actresses took advantage of the rare opportunity to bring a carefully molded script to life, to play characters who are both inconsequential and great. That these characters are so ordinary and yet so compelling is exactly what makes the movie work so well.

Close, who tends to cruise lazily on her brittle, over-the-top persona, is close to heartbreaking here: She softens the steeliness of her eyes only at the most crucial moments; she allows you to see right into the character only when it's absolutely necessary, and the rest of the time she shields herself from both us and the world. It's a performance that trusts the audience to pick up on subtleties, a way of making viewers part of the action.

Flockhart -- who is clearly talented if pictures like "A Midsummer Night's Dream" are any indication, but whose mincing character in "Ally McBeal" is the stuff my own nightmares are made of -- is a nervous bird of an actress, all fine bones and enormous, blinking eyes. She uses those qualities astutely here, suggesting a wealth of iron reserve beneath that frailty. Diaz, whose gifts as a comic actress are only beginning to flourish, plays her character so breezily, and with such wisecracking aplomb, that you begin to think of her as a funny person first and blind person second. (She has no trouble getting dates because, she tells her sister wryly, "guys like to do the blind girl.")

"Things You Can Tell" also makes a fine showcase for Hunter, the miracle actress, a woman who can drive home emotions as nebulous as hurt feelings or buried sorrow just by shifting her gait. Hunter's pixie smile and vinegary little voice may be her most memorable attributes, yet they're never the first things I think of when I recollect her performances. Here, she's a middle-aged woman who makes an abrupt decision to have an abortion, and she convinces us that it's the right decision -- only to be seized with regret that she can't really explain herself.

Hunter has that rare blend of intuitiveness and intelligence; you feel she's appraising the world every minute, just waiting for it to disappoint her, only to find that she's not quite sure what to do when she realizes she has disappointed herself. There's so much toughness even to her uncertainty. Hunter's performance, like all the others here, is so good that it really does belong on the big screen. The fact that we can see it only on the small one is no reflection on its quality, or on the worth of Garcia's movie. Shrink it down all you want; "Things You Can Tell Just by Looking at Her" is still as big as life.

Shares