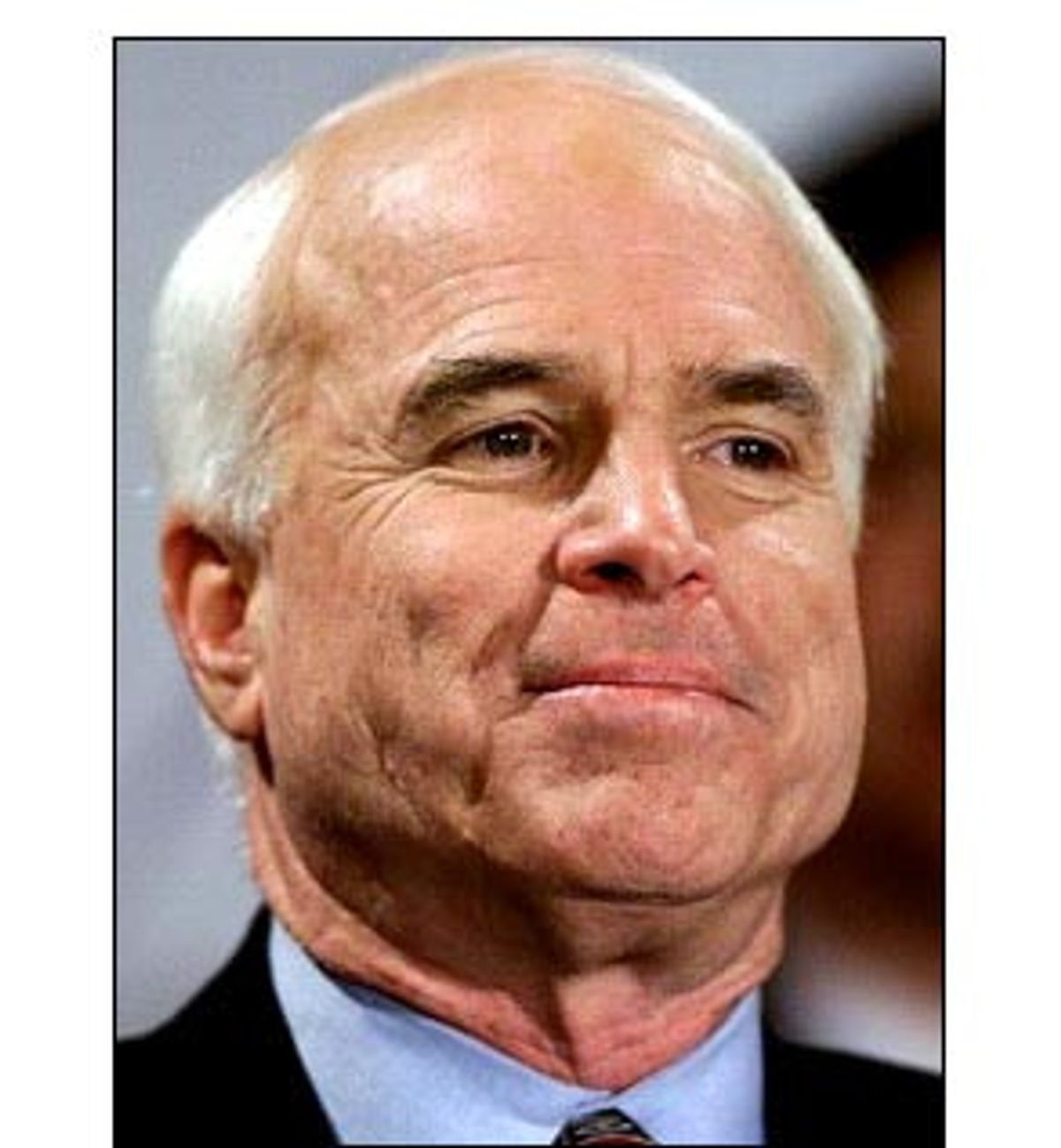

Sen. John McCain shrugged. It was Sunday, and McCain's political director, "Sunny" John Weaver, told the Arizona Republican that Democratic Sen. John Breaux of Louisiana looked like he was finally, officially, peeling away from McCain's campaign finance reform bill.

On CNN's "Late Edition with Wolf Blitzer," Breaux had said that the public really wants politicians to "report the contributions and to make sure that they know where the money is coming to finance the campaigns. But I don't know that eliminating the so-called soft money or carpet money allows us to have a level playing field."

This, even though Breaux had voted for the McCain-Feingold bill -- and its ban on "the so-called soft money" -- five times before.

But McCain, in San Francisco with Sen. Russ Feingold, D-Wis., for a town meeting on this very issue, greeted the news of Breaux's comment matter-of-factly with a "huh," and an immediate change of the subject. After all, there were three Democratic senators whom McCain and his team never counted as supporters in their head count -- and Breaux was one of them. They had always suspected Breaux -- whom Weaver generously labels "a transactional politician," someone who negotiates his every vote with little principle in mind -- would drop the reform flag if and when it ever really mattered.

And next week, when the Senate begins debate on the issue, for the first time maybe ever, it matters.

Campaign finance reform stands a better chance of passing in Congress than at any time in the last decade. That's a victory for McCain, who has single-handedly brought more attention to the topic than any other politician in America. It's his issue. And that's helped burnish the maverick image he sought so hard to project during his surprising, if unsuccessful, 2000 run for the presidency. That run changed things a bit once McCain returned to his old job. "He's the only Republican senator who has a national following," says Sen. Chuck Hagel, R-Neb., one of the few senators to endorse McCain's presidential bid, and a close friend. "That gives him a tremendous amount of new leverage and power as a United States senator."

McCain's role in the Senate "is almost undefinable," Hagel says. "This guy's a different cat. Nobody knows how to handle him. He's got this amazing rapport with the press and the people, especially young people. You can't not deal with it."

Since the beginning of this Congress, McCain has used this leverage -- rooted far more in the power of his own fiefdom than in his relationships with other senators, especially those in his own party -- to push forward issues he cares about, ones often at odds with the new president's agenda: closing the gun-show loophole, an issue he's working on with Sen. Joe Lieberman, D-Conn.; an HMO patients bill of rights, an issue he's working on with Sens. John Edwards, D-N.C., and Ted Kennedy, D-Mass.; and another military base closing commission, on which he's working with Sen. Carl Levin, D-Mich.

So why have opponents from both sides of the aisle, including his closest Senate friend, lined up to shoot his campaign finance legislation out of the water?

"I have no illusions as to how cynical this entire exercise will be," McCain says. "Any special interest that views this as a threat to their influence here in Washington is going to be opposed and I think that if we -- and I emphasize if -- get close to passage, it will soon become near-hysterical."

The hysterics have already begun, even before the McCain-Feingold bill is introduced on Monday. The standard hodgepodge of anti-McCain-Feingold interest groups has lined up, of course, like the Christian Coalition and the National Right to Life Committee and the American Civil Liberties Union. But there are some new faces this year: "The AFL-CIO and the National Right to Work Committee!" McCain announces with glee, relishing how even the bitterest of political enemies find common ground by opposing his efforts to ban soft money.

McCain's favorite movie is "Viva Zapata!" starring Marlon Brando as the titular leader of a doomed Mexican peasant uprising. His favorite book is "A Farewell to Arms," Hemingway's tale of a doomed war romance. He's a lover of principle, even if it means championing a lost cause. And yet in many ways he can ill afford to have McCain-Feingold suffer another noble defeat, because the unfolding drama around the bill concerns more than just reforming campaign financing. It will test McCain's post-campaign national popularity, his ability to work with (or around) an antagonistic White House, and a close friendship with a fellow senator who in this debate is shaping up to be his greatest opponent.

When it's all over, what's at stake is not just his pride, but his influence on Capitol Hill.

Of course, in the end, whatever passes the House and Senate hits the president's desk for a John Hancock or a veto. Here McCain-Feingold's potential doesn't look so promising. President Bush has said he opposed the bill in its final form. But beyond that, Bush and his team have been doing everything they can to marginalize McCain -- even going so far as to send their Senate liaison, Sen. Bill Frist, R-Tenn., to try to negotiate with Edwards and Kennedy on the patients bill of rights, shutting McCain out of his own bill. The animosity toward McCain held by both Bush and his senior adviser, Karl Rove, make defeat of his campaign finance bill that much higher a priority.

On Thursday afternoon, Bush issued his "reform principles," which support unregulated, unlimited soft money from individual voters, though not unions or corporations. Said Scott Harshbarger, president of Common Cause, "The Bush plan would let Denise Rich give as much soft money to the parties as she wanted. The Bush plan would let Roger Tamraz or Rupert Murdoch or Dwayne Andreas, or any other corporate titan or favor-seeker, launder unlimited amounts of money into federal campaigns through the parties."

McCain's response was far more cautious. "We applaud the president for beginning to engage the Congress on the vital issue of campaign finance reform," McCain and Feingold said in a joint statement. McCain will try to keep his comments tempered; he knows that the media wants to paint this story as "Bush vs. McCain, Round 2," but he doesn't want that. Frankly, he can't afford to have his power tied to this bill and thrown into the Potomac River. Hagel says that McCain's national popularity should mean the exact opposite reaction from the White House.

"That means the president has to deal with him not just as a United States senator but as someone who was an equal at one time, someone who bested him in some of the primaries," Hagel says. "The platform that John works from now vs. that before he left [to run for president] is considerably elevated."

And yet Hagel is in perhaps the best position to take him back down a peg. Hagel is offering his own campaign finance reform bill, one that has the tacit support of the Bush White House. The Hagel bill would require that the funders of all political TV ads be disclosed, and would raise the individual contribution limit of "hard money" contributions to individual candidates from $1,000 to $3,000, roughly what inflation has done to the worth of the thousand-dollar limit since it was set post-Watergate.

More controversially, where McCain-Feingold would eliminate soft money, Hagel's bill would simply cap it at $60,000 per donor per national party, per election cycle.

To McCain-Feingold fanatics, this is heresy. "I'm really disappointed in Chuck," says Weaver. "I know he offered his bill sincerely. But Karl Rove and McConnell and the special interest crowd have hijacked it and turned it into a gilded Trojan horse for opponents of reform."

To the McCainiacs, Hagel's bill is not a compromise. "Hagel is not 'in the middle' of anything, Hagel is for soft money," McCain said at a Wednesday press conference with several conservative House "Blue Dog" Democrat supporters of his bill.

To McCain, Feingold and the various good-government groups supporting their bill, banning soft money is the paramount issue in campaign finance reform. Corporate money has been banned from federal campaigns since passage of the Tillman Act in 1907; union funds have similarly been barred from campaigns since passage of the Taft-Hartley Act in 1948; and individuals have been limited to $1,000 per candidate per election since the post-Watergate reforms of the early 1970s. "Soft money lets candidates benefit from money from prohibited sources, like corporations and unions, and in prohibited amounts, as in the cases with the individual contributions," says Common Cause spokesman Jeff Cronin.

McCain is used to the bipartisan dynamics that emerge when it comes to maintaining the status quo.

In 1999, after all, GOP Majority Leader Sen. Trent Lott, R-Miss., and Sen. Mitch McConnell, R-Ky., were blamed by the media for the defeat of McCain-Feingold as the bill failed to garner the support of 60 senators for "cloture," that is, to prevent a filibuster and force a vote on the bill.

But McCain has said that the blame should have been shared equally with Democratic senators like Minority Leader Sen. Tom Daschle, D-S.D., and Sen. Bob "the Torch" Torricelli, D-N.J., for the bill's defeat.

He understands why Democrats are hesitant to embrace his bill, which eliminates "soft" money, the unlimited, largely unregulated donations to political parties that are supposed to be spent on unspecified "party-building" activities that in practice are increasingly spent on advertising to aid specific federal candidates. "Republicans took in $244 million in soft money last year, Democrats $243 million," McCain says. "It was 54 percent of their money, and only 41 percent of our money." So Democratic opposition is common sense. Or, as McCain puts it, "Duh!"

"True believers feel that if someone comes into your office and cuts a six-figure check to you, he wants something," says McCain's chief of staff, Mark Salter. "And then you might subsequently vote in a way that is contrary to your principles. If money is capped at five or 10 thousand" -- as it is with hard dollar contribution limits from political action committees, which limit it to $5,000 per candidate per cycle, so $10,000 total for both a primary and an election -- "a senator won't do that, won't vote a certain way because of that small contribution, but with $120,000 he or she might."

Says Hagel, "I think there is a place for soft money in the system." Soft money cash is used to fund voter education and get-out-the-vote activities, Hagel says, and there's nothing wrong with that as it relates to the parties. "The problem is the unaccountable, unregulated soft money contributions from individuals who fund these interest groups that play out there all the time and nobody knows who they are or what they're spending. That's where I start on this issue."

Thus, Hagel's bill requires greater disclosure of the funding of third-party groups that take out TV ads. Like, for instance, all those nefarious third-party groups that "spontaneously" cropped up in the closing weeks of the South Carolina primary to slam McCain? Or "Republicans for Clean Air," a bogus "interest group" created by one of then-Gov. George W. Bush's biggest supporters -- and put together by a host of Bush allies who left no discernible fingerprints tying them to the Bush campaign -- that funded a TV ad campaign in key primary states that claimed McCain's shoddy record on the environment compared unfavorably with Bush's disastrous one?

"Yes," Hagel says. Those groups. But meanwhile, Bush has instructed Rove to work with Hagel on his version of reform -- assistance Hagel has welcomed.

But isn't Bush the same guy whom Hagel, on the night of the South Carolina primary, referred to as having "mortgaged" his political future by participating in campaign sleaze?

"That's all true," Hagel says. "And we're gonna find out if [Bush] means it. I could always be glib about it and say there's always redemption. But he's told me to my face that he does want to sign a bill and he does want to see the system cleaned up. And until he does differently, I'll believe him."

To Hagel, Bush's support of his bill is that first mortgage payment. "I said that [South Carolina] would come back and affect him, and he would have to respond," Hagel says. Bush's support of his bill, Hagel suggests, is perhaps his way of "dealing with some of these things with the groups he did, in allowing that stuff to happen. This will be a good test to see if he has the courage to see what went on down there was wrong."

McCain's cosponsor, Feingold, doesn't quite see Hagel's bill that way, with or without Bush's support. "Hagel's bill makes a mockery of our attempt to get rid of soft money," Feingold says. "It's not a compromise; it institutionalizes soft money forever." Unlimited soft money could still be channeled through state parties, Feingold says. Besides, he says, when you put together the $60,000 cap with Hagel's provision to increase the hard money limits, by Feingold's math that means that the amount of money one married couple can give to a candidate is $540,000 every two years -- hardly much of a crackdown.

The McCain-Feingold committee, a bipartisan group of senators backing the bill, includes 10 senators who will meet every day to decide which amendments to support, which to oppose. In addition to McCain and Feingold, Lieberman and Levin, the others include Chuck Schumer, D-N.Y., Olympia Snowe, R-Maine, Susan Collins, R-Maine, Jim Jeffords, R-Vt., Fred Thompson, R-Tenn., and Thad Cochran, R-Miss.

Everyone else is suspect. As are some even within this group.

"I'm keeping my eye on every single member of the Senate," says Feingold. "The Democrats have been there consistently on this issue," he says, "but we're shooting with real bullets this time," since the bill could actually pass. Feingold doesn't buy arguments that Democrats will be hurt more by the bill since a greater proportion of their cash comes from soft money donations. "I can't believe any Democrat in his right mind thinks that with a Republican president, and Republicans in charge of both houses, we're not going to get clobbered next time on raising soft money," he says.

This year's incarnation of McCain-Feingold is much tougher than the October 1999 streamlined offering, which was just a soft money ban.

The present bill would accomplish that task, but it would require disclosure on who is behind funding TV ads that cost more than $10,000 a year, and would ban third-party ads that discuss a candidate within 60 days of a general election.

In October 1999, Democrats whom McCain views as part-of-the-problem soft-money lovers -- Democratic Sen. Harry Reid of Nevada, the ethically challenged Torricelli of New Jersey -- attacked the straight-up soft money ban, claiming it didn't go far enough. So they replaced it with the House version of the bill, offered by Reps. Marty Meehan, D-Mass., and Chris Shays, R-Conn. Predictably, it then failed. But Democrats like Torricelli -- then head of the Democratic Senatorial Campaign Committee, leading the charge on a record year for Democratic soft-money raising -- were able to claim that they supported campaign finance reform while ensuring its defeat.

Similarly, McCain and Feingold anticipate that the attempts to defeat their bill this year will come not with an up-or-down vote in favor of the bill, but with sneaky parliamentary maneuvering, such as with a so-called "poison pill" -- an amendment that will make passage of the final act impossible. McCain saw Sen. Judd Gregg, R-N.H., do this to his 1998 omnibus tobacco bill, which would have enacted a global settlement of state lawsuits against the tobacco industry and restricted the marketing of cigarettes. Gregg offered an amendment that removed all liability limits for tobacco companies, a boondoggle for trial lawyers that liberals like Sen. Paul Wellstone, D-Minn., could cheerlead in support of, but which made final passage a non-starter.

Liberal Democratic purists joined with much of the GOP caucus in adding Gregg's amendment to the tobacco bill. Bye-bye, tobacco bill.

It's in these shadows of Senate arcana that those plotting against McCain-Feingold will hide. "That's why John McCain and I have agreed to vote together on all amendments, and not let anyone drive a wedge between us," Feingold says.

Nonetheless, with Bush's support, Hagel's bill might actually be the one gaining momentum, especially as Democrats begin to abandon ship. Breaux is on board, as is his fellow Louisiana Democrat, Sen. Mary L. Landrieu, who is also a co-sponsor of McCain-Feingold, which she says is her first choice. But Landreau is positioning Hagel's bill as a compromise, a second choice, which is the last thing McCain wants to happen. If, say, Miami's powerful, infamous Fanjul brothers -- sugar barons Alfy and Pepe -- can still give more than $2 million in soft money to the party of their choice under Hagel's rules, where's the reform?

Will this drive a wedge between McCain and Hagel, one of his few stalwart supporters in the Senate?

On March 8, the Senate GOP conference met to discuss campaign finance bills. First to speak was McConnell, who has long led the charge in favor of allowing as much money from as many sources as possible, under the tent of the First Amendment. Then McCain spoke. And finally, Hagel.

The first thing Hagel did was pull a "McCain for President" pin out of his pocket and pin it in his lapel. Everyone laughed.

"John, I want you and everybody in this room to know that I'm still dedicated to you," Hagel said. "I am hereby professing my undying love and affection for you, even if we disagree on this issue."

McCain smiled. "Boy!" he said to Hagel. "I'm gonna call you, boy! When I call you this weekend you better get on the phone, boy!"

Hagel laughs while recounting this story, and he says that nothing could come between him and McCain. The bottom line is that "the president is going to be in this mix at some point, and the president has said he will not sign McCain-Feingold as it is. But if we all keep our heads about us, we can do something to improve the system."

The thing is, in McCain's view Hagel's bill doesn't improve the system. McCain considers soft money to be a pernicious influence on politics, and it may well be that his friend Chuck Hagel's bill is the one that robs him of his best -- and perhaps last -- chance to kill the beast.

And when this happens, the longer-term question for McCain will be: Will it reduce his effectiveness? Will it increase how bitter he and his staff (and sympathetic journalists) are about the state of American politics and the Bush White House? Will it push him that much further toward feeling like Zapata?

"But what a way to go!" McCain says of Zapata, laughing. But of the AFL-CIO and National Right to Work Committee joining hands, the defection of Breaux and the poison pills about to be fed to his creation, McCain says, "It doesn't faze me. It used to really upset me. But, ya gotta just keep pressing on. And recognize that there's millions of Americans out there who want me to do the right thing."

Sitting in his office earlier in the month, a TV broadcast of the Government Reform Committee hearings on the Marc Rich pardon blaring in the background, McCain finds it all a little ironic.

He smiles when reminded of the comments of his fellow Republicans who express shock and dismay that Marc Rich bought himself some justice. Influence, justice, legislation: all bought and sold every day in the House and Senate, he says, through soft money. The RNC and the DNC routinely ask big donors for large soft money contributions, purportedly for various "trips" or "events," though the quid-pro-quo is clear. Or as clear as it ever gets in Washington these days, where fundraisers fill out questionnaires for congressional candidates, where lobbyists on occasion write laws, where the coal and energy industries can lean on a few senators and the White House -- so that not even two months into his term, President Bush will do a 180 on a campaign promise to reduce CO2 emissions.

"There's one difference that might be lost on the American people," McCain says in a discussion of the nuances of the Rich pardon controversy vs. everyday life in the Beltway.

"They came to Clinton and offered money for the library and for the DNC in exchange for a favor. We go to them and say, 'Give us money if you want to go to Puerto Rico with Democratic senators, or to the Super Bowl with Republican senators and powerful committee chairmen.'"

He takes it down one notch further. "What we're talking about here is bribery," McCain says, motioning towards a newspaper headline about the Rich pardon. "That's bribery. What we do is extortion."

Shares