There’s a tacit understanding that a genius need not be held to the same standards of behavior as the rest of us, because talent is so attractive and luminous that the average person will endure anything to stand in the company of brilliance.

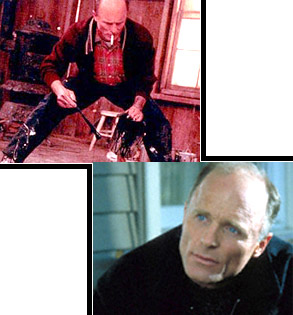

One such genius was abstract expressionist painter Jackson Pollock, whose life is currently on display in the movie “Pollock,” directed by Ed Harris, who also stars in the title role. Pollock was arguably the greatest American painter of the 20th century, but he was also, by any standards, a self-absorbed, abusive alcoholic, and those around him paid the price for helping him make his mark. The target for most of Pollock’s ugliness was artist Lee Krasner (played in the film by Marcia Gay Harden), who was, by turns, Pollock’s wife, his caretaker, his mother and his mouthpiece. Harris’ film portrays Krasner as a woman who sacrificed her own painting to support Pollock’s groundbreaking work.

Given Harris’ background (not to mention an uncanny resemblance to his subject), it’s not surprising that he was drawn to Pollock. Harris’ early work with Sam Shepard and the Magic Theatre in San Francisco established him as an actor of craft, able to capture the energetic explosiveness of Shepard’s early work. He is, however, best known as a screen actor who has taken on meaty roles in films like “Glengarry Glen Ross” and “The Right Stuff.” Harris has been nominated twice for best supporting actor — for his work in “Apollo 13” and “The Truman Show” — and he has recently been nominated for best actor for “Pollock.”

This is your first nomination as best actor. Is it all the sweeter to be nominated for a film you directed and also produced?

I’m glad of the recognition for the film because it’s not a highly commercial venture, and I hope it will encourage some people to check it out who might not have otherwise. I really did spend most of the ’90s working toward making the film and I’m very proud. I was prior to getting a nomination — having a nomination is a little icing on the cake. I’m happy about it.

What initially drew you to the life of Jackson Pollock?

My dad sent me a book in 1986, Jeffrey Potter’s “To a Violent Grave,” which got me going, and I kept reading about him. Then, I got aligned with Steven Naifeh and Gregory White Smith’s “An American Saga,” the Pulitzer Prize-winning biography about Pollock, back in ’91. And the more I immersed myself in it, the more I was drawn to this guy for various reasons, but primarily because of his relationship to his work — how much it meant to him and how he fought and struggled through a lot of obstacles, some of them personal, to arrive at a way of expressing himself that was truly original and truly his own and ultimately, I think, very pure and honest.

In the film, there’s a moment where Pollock is questioned by a Life magazine reporter about his work, and he says about it, essentially, “I’m just painting.” As an actor and filmmaker, do you relate to that approach of working unconsciously?

I think all of the research you do for a role, all the homework, all the years of acting, the technique you’ve learned — you can try to forget about that at the moment of creation. Yeah, there’s something similar about that: what it is to face a blank canvas and suddenly make a line on it and have it be true and honest and not a manipulative thing.

Jackson Pollock was someone who very much lived inside his head. Comparatively little dialogue comes from him in the film. What were some of the challenges of bringing someone like that to the screen?

Pollock was a notoriously nonverbal individual, although, depending on whom he was talking to, and when, he could rattle on a bit. But basically, he was excruciatingly shy and within himself. He was an outsider, from his high school days on.

It was somewhat difficult [to portray him], but I think silence is very eloquent. The film has a lot of stillness in it where you just get to witness him being or painting, or whatever he might be doing. That was very important to me. The film became more subjective in the editing room, and that’s where it lived for me. It’s really not an art history lesson; it’s really a look at this guy and an attempt to capture some kind of essence of him.

The one thing Pollock held sacred was his work. Who do you think he would have been without his talent?

I don’t think he would have been alive too long. He had a very severe problem with alcohol, and he was probably manic-depressive. Life was very tough for him; I think every day was a bit of a struggle. His art was the one thing that really gave him confidence, self-esteem and a purpose. He spent the last year and a half of his life — when he couldn’t paint anymore, when he didn’t know what to say or have something inside him driving him to paint — in a great deal of emotional and physical pain.

You depict Pollock’s work with documentary filmmaker Hans Namuth, who comes to Pollock’s home and attempts to film the painter’s process. The filming as you show it is funny, because it’s anathema to everything that Pollock was about. He was about spontaneous creation, and the filmmaker keeps hounding him to stop painting when he yells “Cut.” The experience seemed to take a lot out of him.

Pollock felt trapped by the process, even though he felt like he had to do it because he had told the guy he would. It really began to disturb him, and it went on for months. The guy would come out, and they would film on the weekends. I think it really started grating on Pollock. He was like the Native Americans who say, “Don’t take my picture — you’re robbing my soul.” I think he started feeling like he was giving something away that he shouldn’t.

And after it was finished, it drove him to begin drinking again for the first time in two years.

It was the straw that broke the proverbial camel’s back. I think he’d had enough.

Was there a challenge, in your mind, to make the film reflect visually what was going on in Pollock’s mind?

I didn’t want to make an abstract film about an abstract painter; I wanted to make a film that was accessible, and I didn’t want it to draw attention to itself technically. I wanted it to be very straightforward and pretty simple, and let what you see speak for itself. That’s pretty much how we approached it.

I mean, there were some attempts to film the paint falling slow-motion onto the canvas, etc., but anything that reeked of “Look at this” I took out. It didn’t belong in the movie.

There are a number of paintings shown in the film that look like Pollock originals. Were they?

One of the greatest challenges to me was to present the work accurately, because he really lived with his work; it really was his life. We got permission from the Pollock-Krasner Foundation, from Charles Bergman and the president, Eugene Thaw, for rights to the images.

At first, I was going to try to film the images at the retrospective and then CGI [computer-generated image] them into the movie, which would have been incredibly expensive. Our production designer, Mark Freedberg, said he could get great scenic artists to re-create Pollocks, because no one was going lend them to us — you know, the insurance alone would be the budget of the movie. So a group of artists re-created his masterpieces, and I was blown away. I really didn’t think it could be done. They work great cinematically, and that’s one of the aspects of the film I’m most proud of.

You yourself painted in the film. You’ve been painting for a while in preparation. How’d you learn to do it?

The drip-pour technique is something that I studied myself and worked on for a good eight or nine years prior to filming. I built a studio on the lower part of my property so I could work on larger canvases. I really wanted to get to a point where I could paint for myself — not so much imitating Pollock per se, or painting in his style, but trying to create something that meant something to me and learn what it means to face a canvas and to live with the work you’re trying to create.

Any plans to exhibit these paintings in the future?

No. They were really more of a process than doing something to try to put in a gallery somewhere.

Was the experience of directing fulfilling for you?

It was certainly challenging, and I did relish not so much being in control, but having the say-so over what this film would become, because I’d worked so long and hard on it. I would like to direct again in the future, but it would have to be something that was very personal, that I would need to do, and it probably won’t be anytime soon.