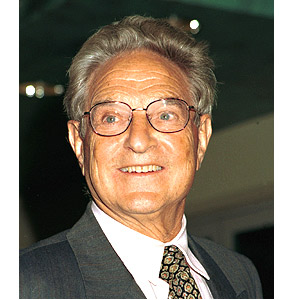

Last year, when the great investor George Soros retired, at 70, from his career of speculating with billions of other people’s dollars, it was as if a legendary athlete — his fingers covered with championship rings — had grudgingly given up after a couple of humiliating losing seasons. Soros’ lifetime record was astonishing: If you had invested $1,000 in his Quantum Fund when he started out in 1969, he would have turned your paltry grand into $4 million by the new millennium — a cumulative 32 percent annual return, the financial equivalent of a major-league slugger batting .400 not just for a single season but for three decades.

Like John D. Rockefeller in a previous generation, Soros found making his billions to be very stressful, and he took much more pleasure in giving them away. Even though he has already given $2.8 billion to his foundation, Soros is still worth around $5 billion. He has promised to give away the rest of his wealth before he turns 80, meaning that his legacy as a philanthropist and reformer could be even greater than it already is.

Soros achieved his lasting fame early on: Back in 1981 he was hailed as “the world’s greatest money manager” by the bible of the trade, Institutional Investor, which wrote: “As Borg is to tennis, Jack Nicholas is to golf and Fred Astaire is to tap dancing, so is George Soros to money management.”

Only one other individual — the famed Warren Buffett — rivaled Soros as an investing wizard for the long stretch from the ’60s through the ’90s. Buffett’s approach was dreadfully prosaic — he lived in Omaha, Neb., of all places, bought stocks in a few supersolid companies (among them Coca-Cola, Disney, ABC and the Washington Post) and held onto them forever. Soros, in contrast, was the epitome of guts and glory. He was a short-term speculator who made terrifyingly huge bets on the directions of financial markets.

No wager was bigger than the time in September 1992 when he risked $10 billion — billion with a B — that the British pound would fall. His instinct was right: That night, while Soros slept in his apartment on New York’s Fifth Avenue, he made $1 billion from the trade. Ultimately his profit reached almost $2 billion — and earned him international notoriety.

From that point on, Soros had guru status among traders, who believed that he could move markets single-handedly. Presidents and prime ministers constantly feared that Soros would bet against their currencies, and the sheeplike denizens of Wall Street and London’s City would follow him, resulting in sharp devaluations and economic crises. Malaysia’s chief of state demonized him for allegedly ruining that country’s economy during the Asian financial panic. Soros gained a reputation as one of the few names — along with Buffett and Alan Greenspan — that had oracular status in the global economy.

And then it all went to hell. Soros lost $2 billion in Russia’s default in 1998. The following year he made a big bet that Internet stocks would fall. The basic idea was right, but he was about a year too early, and he quickly lost $700 million. Then he rushed to buy up a bunch of tech stocks, which sank. His embarrassing losses mounted to almost $3 billion when the NASDAQ ultimately did crash in the spring of 2000. That’s when Soros announced that he was withdrawing from an active role at Quantum, which he would transform from a high-risk speculative fund into a conservative institution — a move like Babe Ruth pledging that he would only try to hit singles from now on.

Soros wasn’t the only legend who suffered an embarrassing fall. Another famous speculator, Julian Robertson — who managed money for New York glitterati such as writer Tom Wolfe — lost billions and had to close down his Tiger Fund last year. Even Buffett had a bad slump. For the small-time day trader at home, moaning as he watched CNBC and logged on to E-Trade and figured that he had just blown the kids’ college tuition fund, it was oddly comforting. It was like watching Tiger Woods triple-bogey every hole on the back nine. If even he could be such a duffer, then you had an excuse.

But even as Soros retired from Wall Street, his influence in the world had never been greater. For two decades his true passions had been philanthropy and political influence, not investing, and by 2001 he had put a stunning $2.8 billion into his foundation, which promotes liberal democracy throughout the globe. Since 1980, when he began giving financial support to dissidents and human-rights movements such as Poland’s Solidarity, no private citizen has done more to promote reform in Eastern Europe and the former Soviet Union. Newsweek called him “a one-man Marshall Plan.”

In the ’90s Soros expanded his efforts to Africa, Latin America and even the United States, where the paragon of capitalism became a cult hero to the bohemian counterculture for his outspoken criticism of the drug war and his financial largess for groups advocating drug legalization and medical marijuana ballot initiatives. Although the $30 million he has given toward changing drug policy is a mere crumb of his overall philanthropy, it has helped to remake his image in this country from capitalist kingpin to progressive savior. While Buffett is famous for sipping Cherry Coke, Soros — who doesn’t smoke tobacco, let alone pot — is most celebrated for fostering cannabis clubs.

– – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – –

Soros was born in Budapest in 1930 as Dzjcgdzhe Shorash and grew up in a family of haute bourgeoisie Hungarian Jews. His father, Tivadar, was an attorney who worked very little, preferring the pursuits of a bon vivant. He owned real estate and published an Esperanto journal. Tivadar’s life of comfort and leisure, made possible in part by a good marriage, came after a perilous youth. He was a lieutenant in World War I when he was taken as prisoner of war on the Russian front and exiled to Siberia. He escaped and lived as a fugitive through the tumult of the Russian Revolution.

Those survival skills were crucial to the family when the fascists invaded in World War II. Tivadar bribed government officials for false identity papers so his son could pretend to be the godson of a gentile bureaucrat. For a period, the family hid from the Nazis in nearly a dozen different attics and concealed stone cellars.

After the war the teenage Soros moved to England (he was inspired by BBC broadcasts) and scrounged odd jobs. As a waiter at Quaglino’s, a posh restaurant in London, he wasn’t too ashamed to scavenge the leftover profiteroles. In 1948, at age 18, he supported himself by harvesting apples and painting houses before enrolling at the London School of Economics.

Soros was strongly influenced by one of his professors there, Karl Popper, author of “The Open Society and Its Enemies.” At a time when leftist intellectuals still had faith in the Marxist religion, Popper argued that Communism was as condemnable as fascism, since both were repressive and intolerant. Popper’s ideas resonated with the young Soros, who had lived under the Nazi and Soviet occupations and had seen both regimes firsthand. Decades later, Popper’s conception of the “open society” would be the basis for Soros’ philanthropic efforts — he would even borrow the term for the title of one of his own books.

Soros aspired to be an intellectual luminary like Popper, but his grades weren’t top-notch and he had to struggle for his subsistence. During one break from school he did a stint as a night-shift railway porter. In 1952, after receiving his degree, he worked as a handbag salesman before finally getting in the door at a London investment bank. Four years later he moved to New York with only $5,000.

Soros began to establish himself as a junior trader on Wall Street, but his real ambition remained to become an intellectual in the grand European tradition. Through the early ’60s he tried to rewrite his philosophy dissertation so he could publish it as a book, but his efforts frustrated him.

“There came a day when I was rereading what I had written the day before, and I couldn’t make sense of it,” he later reminisced in his 1995 book, “Soros on Soros.” “That was when I decided to get back into business … I thought that I had some major new philosophical ideas, which I wanted to express. I now realize that I was mainly regurgitating Karl Popper’s ideas.”

While Soros was what he liked to call a “failed philosopher,” he excelled as a money manager. In 1969 he went out on his own and established a private investment partnership, or “hedge fund,” that would evolve into what is now the Quantum Fund. His success was quick and conspicuous: Throughout the awful bear markets of the 1970s, when most investors lost money, Soros’ fund was profitable every year, and sometimes he even scored double-digit returns. Quantum had only one losing year in its first two decades — ironically, it was 1981, when Institutional Investor jinxed Soros by putting him on its cover as “the world’s greatest money manager.”

But Soros’ biggest embarrassment came in October 1987: For a Fortune cover story titled “Are Stocks Too High?” Soros predicted that the U.S. market wouldn’t fall. Only days later Wall Street suffered the crash of ’87. Soros took a $300 million hit, making him one of the biggest losers in the debacle. But even with that big blow, Quantum was actually up 14 percent for the calendar year — a year when Soros’ personal compensation of $75 million made him the second-highest-paid man on Wall Street. He could pull triumph out of disaster.

Soros settled into his reign as the King of the Street. In 1992, the year that he made his gutsy $10 billion bet on the British pound, Soros’ compensation was $650 million. It was the most lucrative year for any individual in Wall Street’s recent history. (Even Michael Milken reported an annual income of only $550 million at his peak.) In 1993, Soros topped the rest of his peers by making $1.1 billion, which was more than the annual profit of the McDonald’s Corp. Financial World calculated that Soros’ pay was greater than the gross national product of 42 nations. In retrospect, a billion bucks a year seems relatively modest compared with the Internet fortunes of the late ’90s, but back then it was real money.

Soros’ success sprang partly from his extraordinary energy and relentless drive. He often tested the stamina of his butler and cook by sleeping for only two hours a night before returning to work. But Wall Street is full of supercharged workaholics, which begs the question: What was Soros’ secret? His basic theory of investing was that financial markets are chaotic. The prices of stocks, bonds and currencies depend on the human beings who buy and sell them, and those traders often act out of highly emotional reactions rather than coolly logical calculations.

Soros didn’t accept the prevailing theory among economics professors, who held that markets are rational, that prices reflect every nuance of hard data and relevant information. He believed that investors influenced one another and moved in herds. Soros’ trick was to try to understand that herd instinct. Most of the time he went along with the mob, but his real killings came from sensing when the trend would turn and getting out in front of the pack.

And how could he tell the timing of the crucial turning points? Like other investors, Soros had colleagues gather information and perform analyses. But he also had an extraordinary gut. He said that he would have an instinctive physical reaction about when to buy or sell. Normally his composure was cool and emotionless, but when he suffered from a bad backache, he took it as an ominous warning about problems in the market. “I used the onset of acute pain as a signal that there was something wrong in my portfolio,” he once explained. “I rely a great deal on animal instincts.”

The Soros Foundations’ push for liberalization in Eastern Europe began with a focus on his native Hungary in the early ’80s as a showcase. One of his first coups was surprisingly simple: His foundation discovered that photocopiers were rare in the country, so it gave 400 machines to libraries and universities as a way of fostering free expression and dissemination of ideas.

Although he started pouring cash into Eastern Europe in the ’80s, it was Soros’ media stardom as an investor that really gave him an unprecedented visibility. “Until 1992, I had difficulty getting an Op-Ed piece on Eastern Europe published in the Wall Street Journal or the New York Times,” he said. From that point forward, Soros’ cash and clout enabled him to hobnob with chiefs of state as if he were one of them. In 1993, after dining with the heads of Moldova and Bulgaria in the same day, he told journalist Michael Lewis: “You see, I have one president for breakfast and another for dinner.”

Soros’ greatest influence, however, came not from his shuttle diplomacy but, rather, from his donations to dissidents and grass-roots political movements, such as the Otpor student group and other organizations that agitated for the overthrow of Yugoslav tyrant Slobodan Milosevic. Soros shrewdly gave money and equipment to scores of tiny independent TV stations, which used the newer generations of scaled-down apparatus to elude the control of repressive regimes as they broadcast uncensored news. Evelyn Messinger, who worked as director of electronic media for Soros’ foundation, recalls flying to Belgrade with a TV transmitter in her baggage to deliver to an operator.

Starting in the mid-’90s, Soros pushed his reform efforts into the United States, most conspicuously with his criticisms of the nation’s war on drugs. He argues that the emphasis should be on treating addicts, not on criminalizing them. Soros supports the Lindesmith Center, a leading advocate of drug legalization. The center is run by Ethan Nadelmann, a rabbi’s son and former Princeton professor, who is one of the most outspoken and charismatic crusaders in the cause. Soros has also funded needle exchange and methadone treatment programs and supported medical marijuana ballot initiatives in seven states, including California and Arizona. Joseph Califano Jr., director of Columbia University’s National Center on Addiction and Substance Abuse, calls Soros “the Daddy Warbucks of drug legalization.”

“I’ll tell you what I’d do if it were up to me,” Soros says in “Soros on Soros.” “I would establish a strictly controlled distribution network through which I would make most drugs, excluding the most dangerous ones like crack, legally available. Initially I would keep the prices low enough to destroy the drug trade. Once that objective was attained I would keep raising the prices, very much like the excise duty on cigarettes, but I would make an exception for registered addicts in order to discourage crime. I would use a portion of the income for prevention and treatment. And I would foster social opprobrium of drug use.”

That kind of approach is still a long shot in today’s political climate. But when it’s voiced by someone with the Establishment credentials of George Soros — and billions to spend — it’s an idea that can no longer be dismissed by the pooh-bahs of the political world.