As a mother and acolyte-in-waiting, I have always been devoutly agnostic. I have delved into the bibles of both religion and parenting with authentic interest; but I have been routinely disappointed and frequently insulted. Occasionally, like the time I nipped through “The Girlfriend’s Guide to Getting Your Groove Back: Loving Your Family Without Losing Your Mind,” I have been grief-stricken and bereft, convinced that no god or guru would inspire me to worship.

But then, just the other day, I accepted Evelyn Ryan as my personal savior. I’m pretty sure that this stout and effusive mother of 10 will cover all my spiritual needs — both religious and maternal. With me, as with so many things, Mrs. Leo J. Ryan of Defiance, Ohio, has killed two birds with one stone.

And I am giddy with relief. First, I have finally had one of those conversion experiences that will allow me to feel a modicum of charity for enthusiastic Christians. Second, I have a guide, my very own Good Book, to thump and dog-ear and annotate. And finally, I am free. I am deliciously unconcerned with the false gods and goddesses who squeal, cajole and finger wag with bad prose and illegitimate authority, who would have me believe that I could not know what is best, that I cannot be quite enough, that I will not do the right thing. And I am thrilled in the knowledge that Evelyn Ryan would find these people hilarious.

Evelyn Ryan, like some of the best personal saviors, is deceased. She is brought to life, however, in “The Prize Winner of Defiance, Ohio: How My Mother Raised 10 Kids on 25 Words or Less,” a book written by Terry Ryan. The first great attribute of this book is that it is not a book about how to be a mother. It purports to be nothing more than a story about Terry Ryan’s mom, who had 10 kids, entered a lot of contests during the 1950s and 1960s, when wit, humor and a dandy way with words could earn an enterprising person a couple of bucks and the occasional toaster.

But it is a book about how to be a mother. In the finest tradition of sacred texts, “The Prize Winner of Defiance, Ohio” is a simple biography of an oblivious saint, a person challenged by events and circumstances so extreme as to be unbelievable in the context of anything less official than a daughter’s deadpan narrative. And it is all there — wisdom, solace, inspiration and a great garbage disposal subplot that offers no particular insights but fabulous yuks.

Evelyn Ryan, married while pregnant at the age of 20, gave birth every two years until she had 10 children. She lived with Lea Anne, Dick, Bub, Rog, Bruce, Terry (aka Tuff), Mike, Barb, Betsy, Dave and her husband, Leo “Kelly” Ryan, who drank a fifth of Kessler’s whiskey and a six-pack of Pabst Blue Ribbon beer every night, in a house where, as Terry writes, “Things went haywire on a regular basis, but if everyone was still standing at the end of the day, we considered ourselves fortunate.”

This is a place where the refrigerator had to be opened with a screwdriver, where food was kept in the hard-to-open clothes dryer to keep the kids from snacking, where 12 quarts of milk lasted two days and Kelly Ryan’s salary at Serrick’s Screw Machine Shop was $90 a week, reduced to $60 a week after liquor purchases.

Here, for example, is how Evelyn Ryan used her clothes dryer with a faulty pilot light:

Every time she used the dryer (at least once a day), she brought out two matches, a pair of scissors, and a fan. Lying flat on her stomach, she would grasp one unlit match with the tips of the scissors, light the second match, use it to light the first, then stick the scissors through the door as far as she could reach. The fan, brought oh-so-carefully to the door with her other hand, was used to “jump the flame,” as Mom explained it. Sure enough, the breeze from the fan blew the flame from the match to the pilot light.

Here is the best part:

Peering over Mom’s shoulder through the little door, we could see a drop of blue fire dance across the dark abyss to land with perfect balance on the gas jet. “There,” Mom said every day of her life at 801 Washington, “that’s a little better.”

These are the moments, firing up the dryer, changing gears on the car by pulling over and pounding them into place with a hammer, when Evelyn would say things like: “I feel that I’m doing exactly what I was meant to do in this life. I’ve never doubted it.”

Talk about a groove. There is more spiritual sustenance in this straightforward anecdote than in 280 pages filled with advice like: “You owe it to yourself, and those of us who look at you, to devote at least enough time to put together at least two ‘perfect’ outfits for day-time wear.” (Note to “Girlfriend” guides author Vicki Iovine: Evelyn Ryan wore a girdle that she patched by melting parts of old girdles together with an iron. She sewed her own nightgowns, one of which she ripped from hem to collar one morning while demonstrating to Dave — successfully, in the front yard — the right way to punt a football.)

It would be possible, of course, to dismiss Mrs. Ryan as a corny throwback, a maternal dinosaur who fails to address, the way Iovine does, the more immediate concerns of today’s mother, like “how to relieve frozen pizza fatigue,” and fails to answer the big questions, like “Exactly when is it that we can have it all?” But Ryan didn’t pontificate — and that is further confirmation of her greatness. She was humble, though rarely demure, and didn’t have a lot of time for that crap. When she wasn’t cooking or washing or catching pitches or walking somewhere to do something (Ryan’s refusal to learn to drive, says Terry, was “an act of independence”), she was thinking at the ironing board or writing prize-winning poetry on the couch.

Ryan’s “contesting,” as it was called in the day, was a little bit like miracle working, which, of course, is the bread and butter of every divine entity. Rather than loaves and fishes, Mrs. Ryan worked most often with 25 words or less, turning jingles for Burma-Shave, Dr Pepper, Beechnut and Paper Mate, as well as poetry for the Toledo Blade, into appliances and money that her family sorely needed.

Her timing, much like that of other well-known holy figures, was remarkable, suggesting a partnership with an unseen higher power. When her son got hit by a car and his bike was destroyed, she won a bike so he could get his newspaper route back. On the Christmas when the family had just $36 to its name, Ryan sprung gifts for 10 kids from a secret prize closet, the bounty of quiet contesting for one year. She won a supermarket spree when the freezer (also won) was empty, and days after the bank called in a second mortgage (taken out secretly by her husband), Ryan won a grand prize that was enough to pay off the loan.

Writes Terry about the time her mom won $5,000 in a Western Auto contest just days before her family was to be evicted from a two-bedroom rental: “With the $5,000 for a down payment, we got a new house. With our mother, we began to suspect we had a direct line to God.”

But this is not a book about a Mother Teresa. It is a book about Teresa’s mother. The Ryans were, in their own way, a religious family, but Evelyn Ryan’s children were very clear about the source of their mother’s astonishing skills: It was Evelyn Ryan. Though their mother loved certain aspects of the church (“For language skills alone,” Mom said, “you can’t beat a good Catholic school education”), she found its representatives to be somewhat hapless and ineffectual. When she called the parish priest during one of her husband’s drunken rampages, he advised Ryan that she was to endure his alcoholism and abuse without complaint in order to “keep the family whole.” Writes Terry, “Mom chuckled openly at this idea. To her, the world’s blind deference to the man of the house was a grand mistake that we should blithely ignore.”

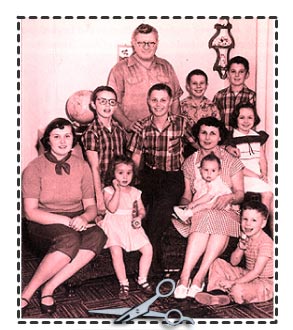

There you go. “The Prize Winner of Defiance, Ohio,” a text illuminated with fine family photos and contest entries, even has a handful of Commandments, not so much handed down as stealthily practiced or delivered in the form of a joke. Old school as they may seem, Mrs. Ryan’s pearls are somehow easier to appreciate than the glibly narcissistic rules of current happy-mommy manuals. I like comments like: “It’s all a matter of what you set out to do” and “Swearing is the sign of a lackluster vocabulary and, worse, a stunted imagination.” Another favorite, which, like all of these gems, can be tried at home: “Do you know that U.S. Army research has shown a relationship between intelligence and a willingness to eat unfamiliar foods?”

Granted, Ryan often saved her pithiest prose for contest entries, delivered to advertising executives from the unassuming mounts of the ironing board or sofa. This was her poetry, work that didn’t betray her frame of mind as much as it demonstrated the quality of her intelligence. Observes Terry: “Our family was often surprised at Mom’s uncanny knack for working complex political issues into something as simple as a Burma-Shave jingle.” Here’s one:

Passed on a hill,

Lived through Korea.

Met a guy

With the same idea.

Burma-Shave.

In addition to homespun copywriting, Ryan dashed off poems that hinted at a stunning tolerance for poverty and abuse while celebrating everything — everything! — including poison ivy, crippling dentist bills and the lack of a front lawn. She never seemed to hold forth — on paper or anywhere else — about certain requirements of forbearance or optimism. But what more could Evelyn Ryan have possibly said about personal joy in the face of adversity than is inferred in this poem, which she wrote while her husband pounded back his nightly ration of spirits in the kitchen?

Hippo Poem

Behold the hippopotamus

bestowing hippo kisses

Upon a hippopotamiss

Who’s not his hippomissus

But he’s no hippocrit, is he,

This hippopotamister

Because the hippopotamiss

Is his little hipposister.

But it wasn’t Evelyn Ryan’s winnings or winning prose (man, was she good) that brought me to my knees. The real transcendental nub in this quiet tale is the astonishing and unencumbered love of Evelyn Ryan’s children for their mother — proof positive of her eminence. In telling the story of her childhood, Terry Ryan wrote about her mother: “I thought my mother capable of any feat, mental or physical,” and “We knew there could never be a problem bigger than Mom’s ability to solve it.”

As an adult, Terry realized: “Here was a woman who never showed the slightest bit of resentment or bitterness. In fact, the reverse was true. Mom delighted in life’s innate hilarity, and her joy in living found its best statement through her gloriously understated ‘knack for words.'” And as her mother was dying of cancer in 1998, all of her children at her side, Terry told Evelyn: “We have never been in danger as long as you’ve been with us. Even after you leave, we’ll carry you with us wherever we go.”

If there is more compelling evidence of Evelyn Ryan’s divinity, I don’t need to see it.

Amen.