About a year ago, at a cocktail party, I met a young man who ran an escort service. He was about 24, dressed in a black leather jacket. He asked me what I did for a living. “Oh,” I said, “I edit an alternative Web site for mothers. We write about all the things that other parenting magazines don’t touch. You know, news, politics. Sex.”

“Sex?” he said. “Oh man, I don’t like to think of mothers having sex.”

And so, I think, even the New Age pimp can’t shake the mother-whore hang-up. It is fine — read: sexy — to want to frolick with prostitutes. This guy’s business depends on it. But the idea of a woman, with child, with sex appeal does not compute.

I digest this morsel easily. It is not my first encounter with the mother-whore dichotomy. Besides, I have a healthy sense of self-satire. It didn’t take me long to find it equally as strange — and telling — that I had felt the need to immediately invoke sexiness as part of my definition of motherhood.

It’s an equal and opposite reaction kind of thing. I accept that motherhood is conventionally thought of as unsexy, and therefore I define myself, among other things, and in certain company, as, well, a hot mama.

Or a hip mama or an intellectual mother or a “single and proud of it” mother or just about any combination of mother that begins with some modifier that is conceived as being outside the conventional definition of motherhood.

But have you ever noticed how many conventionally unconventional mothers there are out there? We congratulate ourselves for our tattoos, piercings, queer partnerships, queer friendliness, single motherhood, young motherhood or sex-toy-enhanced motherhood — or simply for the fact that we wear cool boots and don’t have a minivan or an SUV. (And of course, we use any unconventional items on this list that we have to negate any conventional leanings we might have: For example, I’m a married mother with an SUV, a tattoo and a nose piercing, or a queer mother with a suburban bourgeois lifestyle, or a transgendered i-banker feminist mother.)

All of this self-conscious “I’m a mother but [insert qualifier here]” nattering only underscores the idea that motherhood, in its generic, unqualified form, is looked upon as boring at best, as well as sexless, intellectually bereft and generally depressing. I’m certain there are some sinister, misogynistic forces at work here, as well as a healthy dose of self-hatred and a certain amount of delusion, given that motherhood has always encompassed more than the mainstream stereotype of the good mother. (I sometimes suspect that certain especially pernicious stereotypes — the frigid Victorian matriarch, the ’50s housewife and today’s suburban soccer mom — have never existed as anything but straw women for the firebrands of each generation to set ablaze with our hip, sexy lighters.)

But the fact is that the definition of motherhood does change — often drastically — from generation to generation. Each generation has to reinvent certain aspects of motherhood to make it palatable to women who have had to shrug off the antiquated notions that held sway in previous generations, and to provide a generational continuum between youth and young adulthood. Young womanhood is all about not being one’s mother; therefore when one becomes a mother, one often has good reason to believe that one is not one’s mother’s kind of mother.

The fact that millions of other women are having the same revelation each day at first means that each generation produces an early wave of mothers who insist to anyone who will listen that they are not like the other mothers they know — until they realize that they are exactly like millions of other mothers they know. Then they all band together and produce the mothering manifestos of their generation. It’s nearly Hegelian: thesis (all mothers look like mine), antithesis (I don’t look like my mother, therefore I am not a “mother”) and synthesis (this is what mothers of my generation look like — me!).

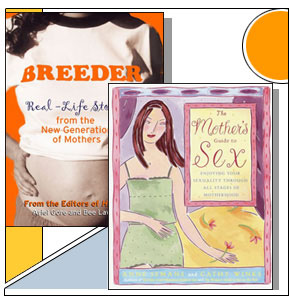

To see what the unconventional women who came of age in the ’80s and ’90s have done with the notion of motherhood, one need look no further than two new books: “The Mother’s Guide to Sex: Enjoying Your Sexuality Through All Stages of Motherhood” by sex-positive feminists and Good Vibrations co-founders Anne Semans and Cathy Winks, and “Breeder: Real-Life Stories From the New Generation of Mothers,” an anthology of essays edited by Ariel Gore (a “29-year-old single mom and the founding editor of Hip Mama”) and Bee Lavender (a “married, homeschooling mother of two and the managing editor of hipmama.com”). Semans and Winks also contribute a regular sex column to Hip Mama.

These are emphatically not mainstream parenting manuals, which is what makes them such generationally specific documents. These are parenting manuals for Gen X mothers who want to see the edgiest parts of their youth reconciled with their new status as parents.

Because both of these books are pitched at women who believe themselves to be outside the mainstream, they combine a self-conscious piling on of cultural references — tattoos, piercings, punk rock, attachment parenting — with the timeless details of maternal life — breast-feeding, giving birth, sex after children, making dinner with no food in the house — that serves to ground the cultural detritus of motherhood in the inescapable biological conditions of giving birth to children and raising them, housing them, educating them and generally keeping them alive.

“Breeder” is less concerned with providing prescriptive rules for parenting than it is with providing descriptive essays on the lives of “real women.” (Don’t you ever wonder where the fake women are?) In her introduction, Gore writes that in her book, “real women who came up during the hippie and punk eras chronicle what it means to be a mama here and now. We aren’t the neo-June Cleaver corporate beauties you see in the mainstream parenting magazines and we aren’t the purer-than-thou organic earth mamas you see in the alternative glossies. We are imperfect and we are impure.”

Gore’s “imperfect and impure” mothers include strippers, teen moms, polyamorists, home-schooling mamas, activist mamas, single mothers “parallel parenting” with other single mothers, American mothers giving birth in foreign countries, surfer mothers, lesbian mothers looking for the perfect sperm donor and more. About the only thing you won’t find in this book is a description of affluent suburban housewife angst.

The territory is both familiar and, for some readers, strange. For example, Kai Ro, in her essay “Big Mama,” writes about the familiar wrangling with nagging in-laws, but she fantasizes about retaliating by telling them, “Your son is a polyamorist with genital piercings. We have an open relationship, and he asks me if it is okay (and usually gets me flowers) before he goes on dates with other women. He’s hidden his tattoos from you for years, since before he met me.” (The fact that she doesn’t actually tell them this seems to imply that she may be more wedded to the concept of what “good” parents do and do not do than she would care to admit.)

“The Mother’s Guide to Sex” is definitely a guidebook — it aims to be the “Our Bodies, Ourselves” or “What to Expect When You’re Expecting” for the sex-positive feminist mother. It’s an exhaustive, 300-plus-page tome that covers everything from sexual self-image (with, of course, a guide to exploring one’s anatomy with a mirror, as well as tips for masturbation and sex toy purchases) to sex during pregnancy (which covers everything from hardcore medical advice on placenta previa and miscarriage to warnings to be on the lookout for medical professionals who practice “sex toy discrimination”) to sex as a married parent (one suggestion is to keep your kid at day care for an extra half-hour and meet your partner at the usual time for sex) to sex as a single parent (the authors recommend that younger children be told that Mommy is having a sleepover, and that older teens be coached in the necessity of enjoying a healthy, happy sex life).

Much of the advice is the kind that you won’t find anywhere else: whether to take out your genital piercings for delivery (you should), whether you can breast-feed with a nipple piercing (you can’t) and whether one should engage in bondage during pregnancy (it’s not recommended, but it can be done if you and your partner are very, very careful).

The authors recommend online chat rooms for bonding with other moms (not surprisingly, since they are also the authors of “The Women’s Guide to Sex on the Web”). Another piece of advice: If you have money woes, sell your extra books, CDs and clothes and buy … sex toys. (At which point, one almost feels that there should be some sort of financial disclosure.) To beat postpartum depression, hire a babysitter and masturbate all afternoon. And if you are uncomfortable with your body, go to a nude beach!

A good portion of the book covers the same territory as other pregnancy and parenting manuals, albeit with a sex-happy twist. While other manuals recommend Kegel exercises as a necessary, but somewhat unpleasant, ingredient of postpartum life, like wheat germ, these girls are all about pleasure, pointing out: “These are the kind of exercises that beg to be done with a penis or a dildo.” One parenting manual suggests that you “refrain from breast play” if it makes you uncomfortable. But the Good Vibes girls say, “You’re better off adjusting your attitude. There’s nothing passive about the spray of milk that shoots out of your nipples upon arousal. So go ahead and make a mess.” Ditto for the “heavier scent” in your vulva. They advise not using the douches or scented oils recommended by some “retro manuals.”

As a young mother, I was never one for parenting manuals, retro or otherwise, mostly because, like these women, I believed that the mothering manuals were not written for people like me. These days, whenever I start spewing some dribble about how I am not like the other mothers, a well-worn monologue that resembles nothing so much as the speech that teenagers give their parents (You don’t understand me! No one understands me! I’m not like the other kids!), there is one person who can shut me up. My friend Sheerly will look at me and say, “Face it. You are your demographic.”

She’s right, of course. And that sense of demographic solidarity is ultimately the experience that one takes away from these two books. Motherhood is all about integrating the rebellious teenage daughter with the mother who repackages the best parts of that rebellion as wisdom. And, as mothers, we are single and married, queer and straight, punks and hippies, virgins and whores.

These are books for the Every-Madonna.