“No citizens of one country have ever been so committed to the success of another as American Jews have been to Israel,” writes Steven T. Rosenthal in his new book “Irreconcilable Differences: The Waning of the American Jewish Love Affair With Israel.” As the title of his book implies, however, the American Jewish community’s consensus on Israel has disintegrated. Rosenthal argues that since the 1980s, disastrous events and conflicts — the invasion of Lebanon, the Pollard spy affair, the Palestinian intifada and the “Who is a Jew?” crisis — have tested the silent, uncritical unity of American Jews. Israel, to a certain extent, disappointed them. At the same time, Rosenthal explains, the American Jewish community has shifted its attention to its internal concerns. In many ways, the initial, rallying goals for the founding and fortification of Israel have been fulfilled, whereas rising intermarriage and declining religious devotion continue to fracture Jewish life in America. Priorities seem to have changed.

Even now, when many American Jews agree that Yasser Arafat is to blame for the end of the peace process, American Jews’ support for Israel hardly compares with their unequivocal championing in the decades following Israel’s establishment. Rosenthal cites a poll that finds that one-third of American Jews are prepared to give up Jerusalem for peace in the Middle East, a position they do not share with the Ariel Sharon government.

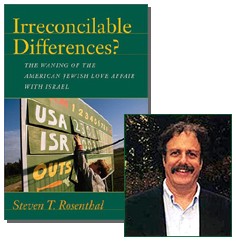

Rosenthal’s book is full of such surprising statistics and ideas. An associate professor of history at the University of Hartford, he is also the author of “The Politics of Dependency.” Rosenthal spoke to Salon from his home in Scarsdale, N.Y.

What was worrisome about the Jewish community’s former reluctance to criticize Israel?

The rationale had always been that Jews do not wash their dirty laundry in public and that doing so could only benefit those who wish Israel ill. Politically, the unity of the Jewish community had always been its greatest strength. But as Israel began making a greater number of mistakes and engaging in questionable activities in the ’70s and ’80s, it became obvious to those who wished Israel well that silence was probably worse than criticism. If Israel continued on the path that it had been going, things would be pretty terrible. Therefore, the cost of speaking out was less than the cost of not speaking out.

Do you think that this book could not have been written 30 years ago?

An interesting point. My book is not a rabble-rousing book. It’s rather moderate. But you’re right, to the degree that dissent was once not tolerated, it would have been extremely hard to publish such a book.

Have you encountered criticism for writing this book?

The book was not taken by a certain book club because it felt that the title was negative. It depends on the time frame. For a long time, I have been a moderate criticizer of Israel; if it were in an Israeli context, I would be in the “Peace Now” camp. I’ve been giving talks about this for a good 20 years. There have been times when I had something thrown at me, but that was many, many years ago. Now, it’s as if the community has caught up. In an American context, I was ahead of the curve, but not necessarily in an Israeli context.

If you look at the traditional Jewish identification with Israel — how it became the lowest common denominator of Jewish identity — that has really changed. A recent poll asked Jews what is the most important component of Jewish identity? Forty-seven percent said “social justice.” Thirteen percent said “Israel.”

That being said, it should certainly be noted that given what has happened since late October in Israel, there has been a rallying around Israel by people who were very pro-peace process, including myself. Right now, there is nobody to talk to. This doesn’t mean that peace as an objective is out the window, it’s just out the window at this particular moment. Many on the moderate left have been devastated by what has happened.

What makes the recent uprising different from the intifada in the late ’80s?

It is a mistake to call both of these eruptions by the same name — intifada — which everybody is doing. The word “intifada” comes from an Arabic word, “to shake off,” as a dog shakes off fleas. That gives the connotation of spontaneity. In contrast to the first intifada, the second “intifada” is not so much spontaneous but appears to be a tactical political decision made by Arafat. He decided that he could not or would not conclude peace. Therefore, it’s not the same kind of spontaneous upswelling.

Do you think the Palestinian people feel they are being manipulated?

The word “manipulation,” of course, is loaded. Is the tail wagging the dog or vice versa? I would certainly assume that Arafat is reflecting the basic thoughts and emotions of the average Palestinian. But everybody is so disillusioned with Arafat because even if that is the case, the function of true leadership is to get beyond that. The mistake that was made by Bill Clinton and by Ehud Barak, and I still think it was a mistake worth making, was to assume that Arafat could be turned into a Nelson Mandela. But Arafat is Arafat and not Nelson Mandela.

Another difference between the two uprisings, of course, is that the first intifada produced lots of movement and progress toward peace. It gave the Palestinians a sense of pride and a sense of self that let them have the self-confidence to negotiate with the Israelis. It demonstrated to the Israelis what they had suppressed: that the Palestinians truly hated them and there was no way they were going to live under that kind of Israeli domination.

And this uprising has done what to the process?

This one has foreclosed on negotiations. If there is one thing that Sharon and George W. Bush now agree about, it’s that the Oslo process is dead and that there is no way that one is going to negotiate a permanent agreement any time soon.

But we still expect that of Israel. I was interested in the idea that Israel has always been thought of as a special moral nation. Lofty expectations have been put upon it. Why is that?

Because the Israelis and the Zionists put it in on themselves. Right from the beginning, one of the appeals from Theodore Herzl was that he was not simply creating another Albania. He was going to create a special nation, which was going to be a light unto the world. In fairness to Israel, given the incredible pressures that Israeli society has been under, what I find remarkable is the degree to which they have made an effort and been successful at it.

What we are looking at now, however, is the basic contradiction between ideology and living in the world. The very nature of being a nation and of having to deal with the issues of power automatically means that you have to compromise.

Which specific ideas of the founding of Israel have been contradicted by actually living in the world?

This idea of extreme morality. The idea that you’re going to be perfect in everything you do. There’s no nation that can do this. Israel’s extreme critics, especially American Jews, want Israel to be perfect because they see Israel as a mirror and as a reflection of their own Jewishness.

Therefore, are people more outraged when Israel does something wrong? For example, the Palestinian massacres by Phalangist forces at Sabra and Chatilla, which were supervised by the Israeli army. Was it more shocking for the Israeli army to have committed war crimes?

Yes. That was not part of Israel’s gestalt. Israel is ideologically formed at least, in part, by the Holocaust. Jews don’t get involved in such things, even indirectly. It should be noted that the largest and most vociferous demonstrations against the actions of the Israeli government came from within Israel by Israelis who were appalled at what their government had become involved in, even if unwittingly.

And the reaction of American Jews?

The reaction of American Jews was, if anything, even stronger because it showed that Israel was no different from other nations; that Israeli leaders could be just as stupid, just as mendacious, just as self-serving as anybody else. That was a shock because American Jews had always had the image of Israel that was found in the movie “Exodus”: Israelis are handsome and heroic and spend their time doing the hora around the campfire.

I didn’t realize that the book and movie had that much of an effect.

It had an incredible effect. The book was everywhere. And the movie was everywhere — American Jews went and saw it like it was some kind of religious experience.

And it was romanticized?

Most of it. It was based on a true incident, but there was this simplicity to it. In the movie, Arabs are not evil enough, so they are goaded by a fugitive from Hitler’s Germany, a Nazi. How unsubtle can you get? But it worked. David Ben-Gurion considered it the best piece of propaganda ever written about Zionism in Israel. It is incredibly powerful.

What kind of effect do you think it had on non-Jews in America?

I believe that it garnered a lot of sympathy for Israel and for Jews. It gave a new kind of image — the image of the Jewish soldier as opposed to the image of the Jew as an intellectual, tortured, weak concentration-camp victim.

How do you think that non-Jewish Americans relate to Israel?

I don’t think that they know enough about Israel. If we’re talking about fundamentalist types, they are very pro-Israel because of their own religious conception that you have to have Jews in the Promised Land for the Messiah to come. Other Americans are pro-Israel and will remain pro-Israel because they seem to perceive Jews as being “just like us,” as opposed to Arabs, who are part of the “great other.” You have a very small amount of anti-Semitism in America, but you still have a very large amount of anti-Arab feeling, and that of course rebounds to Israel’s benefit.

And Americans grow up believing in the image of the Palestinian terrorist, even if they don’t know exactly where it originated.

The media will still play on that. To the degree that people like Saddam Hussein are still in operation, this reinforces the popular image of “the Arab” with all of its negative connotations.

During World War II and the Holocaust, did the American Jewish community lobby hard for America to open its doors or was the focus on Israel?

This is a very complex and somewhat controversial episode in American Jewish history. American Jews flagellate themselves, whether with justification or without justification, that they could have done more to save European Jewry. The Roosevelt administration — ironically, because Roosevelt is a true American Jewish hero — did very little to save Jews, preferring instead to concentrate its efforts on winning the war, stating implicitly that the two efforts were mutually exclusive. They weren’t. American Jews may not have made all of the efforts that they could have, but whether those efforts would have saved many people is debatable. Of course, even if they’d saved a few, it certainly would have been worth it.

After the Holocaust, American Zionism changed significantly.

The Holocaust represented the greatest possible proof of the Zionist thesis about anti-Semitism. Not even the most extreme of Zionists had ever conceived of the kind of mass destruction that occurred in the Holocaust. But American Jews, seeing what had happened, took the lead in the Zionist movement. In 1942, they engineered the passing of the Biltmore Resolution, which stated that after the war there should be a Jewish state. More importantly, after the Holocaust, American Jews abandoned their fears of dual loyalty and massively united in a campaign to convince the United States government to support Jewish statehood at the U.N. It has been argued that without this support it is problematic whether Israel would have come into existence in the first place. It can be argued that the Israelis do owe American Jews a great debt of gratitude.

Truman was in office then. What was his position?

He said he had never been subjected to more pressure in his life. American Jews were seen by the Democratic Party as a crucial political element in the next election. Of course, Truman always argued that it was the right thing to do, not because America felt guilty about the Holocaust — which it did not commit — but because Americans were sympathetic with the plight of Jews.

At the time, were the Arabs perceived as a problem?

It was not a great issue for American Jews. There was a minority tradition in Zionism that stated that you had to worry about the Arabs. However, the mass of Zionists was more influenced by the slogan: “The land without people, the people without land.”

At the time of the Six Day War, it was apparent that the surrounding Arab countries wanted to annihilate Israel or prevent it from ever coming to be.

It took on the language of the Holocaust. There was a very famous interview by the then head of the PLO, an Egyptian lawyer named Ahmed el Shukeiri, on Jordanian television. He was asked what would be the fate of the surviving Jews when the Arab powers conquered the Zionist entity. His reply was that those Jews would be incorporated into a democratic Palestinian state, but frankly, he explained, they didn’t expect more than a handful to survive. Obviously, this kind of talk and the talk of Nasser was a triumph of rhetoric over reality, but in that context no one could even remotely blame Israel for feeling threatened and retaliating.

The Israelis have done a fairly miserable job in public relations. The Israelis’ notion had been that if our policies are correct, we don’t need public relations. If they are incorrect, then public relations won’t help. That’s part of it. There’s also this notion, particularly prevalent in the Labor Party, that American Jews don’t count and one didn’t have to bother cultivating them.

In the Labor Party?

Yes. That’s one reason why the Oslo agreements were not terribly well supported, even by people who did support them. They supported them intellectually but not emotionally. The Rabin government basically made a career of telling American Jews, “You know, we really don’t need you that much anymore.” In an extremely famous incident, Deputy Foreign Minister Yossi Beilin told a group of American Jews that Israel was no longer a poor country and doesn’t need their charity.

Why? What motivated them to do this?

Thirty years of feeling that they were looked down upon by American Jews. They were tired of being a poor relation. Israel now has a per capita income of $20,000. Obviously, this kind of thing by Beilin was dubbed moronic by Rabin, but he did not like the idea that American Jews felt that they could tell Israel what to do.

Do they feel the same way about the support of the American government?

No. That is why it was a bad move. It jeopardized American financial and political support in general. In contrast to the Labor Party, Likud has a much more traditional view of Israel: Israel is in peril and American Jews are needed. This is the kind of scenario that American Jews are familiar with and with which they are comfortable.

But when you talk about the “Who is a Jew?” controversy — the Orthodox rejection of Jews converted by Conservative and Reform rabbis outside of Israel — the members of Likud were more concerned about that, right?

That puts Likud in a much worse position with American Jews. You’re getting a sense of the complexity of the whole situation.

Of course, the Likud era also included the invasion of Lebanon. Does that still weigh on American Jews?

Of course it still bothers them. That is one of the principal pieces of baggage that Sharon carries with him. Sharon was responsible for the Israeli army surrounding Beirut. Originally, the Israeli army had pledged to take only 25 miles to provide a fire-free area where Israel could not be threatened by mortar firings. Instead, Sharon pushed the troops all the way up into Lebanon and, as you probably know, he was condemned by the Kahan commission in Israel and dismissed from the government for his role in Sabra and Chatilla.

Which makes it surprising that he is where he is now — or does it not, given the current circumstances?

In a sense, sure, but it certainly was surprising that Richard Nixon got where he did, given his past. More realistically, many people would concede that this recent election was not so much a vote for Sharon or even so much a vote against Barak as a vote against Arafat.

How powerful are the more conservative populations in Israel today?

Certainly, they are stronger than ever. They are a vital part of Sharon’s governing coalition. He’s given them five Cabinet posts and the question is, Will they be able to exercise power in society and roll back some of the things that were done under the Labor Party? Or does Sharon need a national consensus to such a degree in this difficult time that he will prevent the Shas Party — which articulates many of the conservative desires — from working its will? It appears that, for now at least, Sharon is more interested in a national consensus, especially since he has to establish a reputation as a moderate to counter his baggage.

Do some older Zionists today resent America’s influence?

If you are an old-line Zionist, you are resenting what has happened in Israel in the past decade. What I’m talking about is the phenomena that are collectively grouped under the name of post-Zionism — the notion that there is less of a sense of obligation to the state and to the collective goals that Zionism stood for, and instead there is an increasing sense of individualism and consumerism. This is what old-line Zionists would resent infinitely more than anything that America is doing, except insofar that America has been the model for the change in Israel.

You write that American Jews’ concern for their community in America partly accounts for their waning interest in Israel. How much?

The Council of Jewish Federation Population Survey of 1990 found a 52 percent rate of intermarriage. They also found that Jews spend three days per year at synagogue. Therefore, the new challenge for American Jews has been not so much Israel but that phrase “Jewish continuity.” Just as important in explaining the gradual distancing of American Jews from Israel is a whole bunch of other factors. Mainly, Israel has fulfilled much of its original promise and those needs, which managed to mobilize the mass of American Jews. The desert has bloomed. Israel has the strongest army in the area. It has a pretty healthy economy. Those tasks are what had mobilized American Jews. The last great task for American Jews appears to have been Russian immigration and even that has just about finished.

Has the American Jewish community been more or less critical of how Israel has handled the current conflict than it has been in the past?

The American Jewish community, with justification, is deeply disillusioned with Arafat. One has the problem of asking the Israelis, What are the alternatives? Even when the Israelis have engaged in certain conduct recently, such as the assassination of Palestinian leaders, there’s been very little criticism among the American Jewish community. Everybody is just so disillusioned that in at least the extreme short run, Israel is getting a little bit of a free ride.

But even at the extreme moments of shock and disillusionment, the peace camp began to speak out, maintaining that the hard line provides no blueprint for ending the conflict. American Jews have not given up on peace; they’ve probably given up on permanent peace right at this moment. According to a poll, one-third of American Jews are still willing to give up Jerusalem, which is totally against what the Sharon government is trumpeting.

Do you think that criticism of Israel affected the amount of power American Jews have in influencing the American government’s policies toward Israel?

To the degree that there is no longer unity, certainly. American Jews are less of a factor. It should be noted that in 1988, at the height of the first “Who is a Jew?” crisis, the American government decided that that was the time that they would start talking with the Palestinians. That may not have been coincidental. Interestingly enough, there was almost no adverse reaction from the American Jewish community.

How do you see the American Jewish relationship with Israel changing?

In the short run, it will be about the same. The failure of the Palestinians to grasp the olive branch that Israel offered and the violence of that rejection has ensured that on one hand, the American Jews will not act as a peace lobby against the Israeli government as they did at the time of Benjamin Netanyahu. At the same time, the same Palestinian rejectionism has made it unlikely that the world or the U.S. will apply the same kind of pressure on Israel that has historically caused American Jews to rally around Israel and defend it almost reflexively. Between these two extremes, American Jews will relate to both the Sharon government and the new uncompromising diplomatic conditions, but in a way that they would not have 30 years ago. They will relate on the basis of the independence and the sophistication that they developed in the past two decades. If they support Israel, which at this point they do, it’s not because Israel tells them to but because their own independent judgment has led them to that stance.