“You’re not the Internet,” White House press secretary Ari Fleischer told reporters as he warned them away from reporting on first twin Jenna Bush’s second bust for underage drinking in just over a month.

We are the Internet, over here at Salon, at least part of it, and it was hard not to wonder exactly what Fleischer meant by his dark warning. Actually, I knew exactly what he was trying to say: The Internet is a shadowy place where reputable people don’t go, where rumor and innuendo and bile simmer in the darkness until they bubble up into unsavory news stories, stories that reputable people, sadly, then have to answer questions about. What I didn’t know is whether that’s what Fleischer actually believes, whether he’s missed the fact that for most people, the Internet is not some fringe obsession, but the place to check stock quotes, sports scores and news headlines, buy books and CDs and Gap T-shirts (plus meet new friends; more on that later) — as well as the fact that the Internet had absolutely nothing to do with Jenna Bush making news.

The Associated Press broke the stories of Bush’s alcohol citations, and that makes sense. Her troubles are a matter of public record. She’s an adult, she broke the law more than once and she’s the president’s daughter. Her father has advocated and signed into law tough penalties for underage drinkers. Her alcohol-related mishaps are a legitimate news story, not Internet gossip.

But it was hard not to miss an odd convergence. The same week as Bush’s troubles made headlines, a news story did come bubbling up from the dark reaches of the Internet: the strange tale of gay conservative Andrew Sullivan, and the supposed “hypocrisy” of his lecturing on gay politics and morality while, apparently, he looks for kinky sex on the Internet. His critics, who include gay journalists Michelangelo Signorile, David Ehrenstein and Michael Musto, have in various ways made public the details of Sullivan’s Internet exploits, including his screen handle as well as the online personal “profile” the HIV-positive journalist used as he sought out opportunities for having unprotected sex with men who are also infected with the AIDS virus. Discovered on the Internet, published in print, the Sullivan story then became mainstream news.

The convergence of the Bush and Sullivan stories, as well as the public reaction to them, raises the toughest and most fascinating questions in journalism today: Why are we so obsessed with the private lives of public figures? What kind of privacy, if any, are they entitled to? And what’s “private”? Is hypocrisy a good enough reason to reveal someone’s secrets — and who decides what constitutes hypocrisy? Both have now become “Internet stories” because they’ve taken on a life of their own on Web sites, chat rooms and message boards. Amazingly, in Salon’s letters pages and elsewhere, Jenna Bush has gotten considerable sympathy for suffering media overkill, while Sullivan’s humiliating sexual exposure has been widely applauded.

The reaction is, of course, ass-backwards: The Bush story is news, while Sullivan’s is not.

In fact, the reaction to the Sullivan story has been scarier to me than the story itself. That Sullivan has made enemies is well known. He and Signorile have clashed before over the ethics of “outing” gay public figures who have stayed in the closet, with Signorile opting for exposing their hypocrisy and Sullivan defending their right to privacy. That Signorile would decide, along similar lines, that the public also needed to know about Sullivan’s private sexual practices, in light of his moralistic public statements, doesn’t shock me. I don’t agree, but I’m not surprised.

I am surprised, and a little sickened, by the reaction to the story. Letters on Jim Romenesko’s Media News have overwhelmingly favored Signorile. Sullivan’s foes offer two lines of defense for outing him sexually. One is that he’s preached a fairly (but not unrelentingly) conservative line on sex and AIDS and gay identity. His New York Times magazine article about good news on the AIDS-fighting front, “When Plagues End,” is blamed for creating the illusion that the disease has been conquered, supposedly leading to public and private neglect of the issue. So supposedly, the news that Sullivan himself is practicing unsafe sex (though he and his partners are HIV-positive, they could be exposing one another to new, more virulent strains of the virus) is of public interest, especially in this age of rising HIV-infection rates.

But if public health is the real reason for outing Sullivan’s private sexual behavior, then the names of everyone we know, gay and straight, who practices unsafe sex should be revealed, posted in the town square, in newspaper classifieds and, of course, on the Internet. Of course, the real reason Sullivan’s critics support his outing is payback, pure and simple, despite their high-minded public-health protestations. And that’s appalling. More than a few people have written about Sullivan’s criticisms of President Clinton’s private transgressions when they defend savaging the gay conservative, as though his anti-Clinton writings make his private life fair game.

It seems as if there’s a brand-new, very simple standard for when the private behavior of a public figure is news: when he or she writes something that makes enemies. And that’s indefensible.

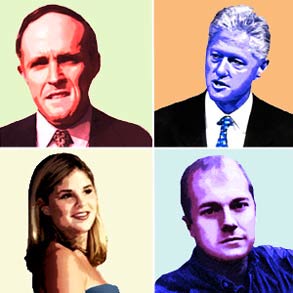

Sadly, Clinton’s impeachment, rather than sobering the country about the costs of sexual witch hunts, actually made them more likely — in the short term anyway. Left-wing Web sites were atwitter with rumors of an alleged affair between Florida Gov. Jeb Bush and a state official last month. Enemies of New York Mayor Rudy Giuliani have luxuriated in the public scold’s very public humiliation over his affair with Judith Nathan. Some people who’ve defended the Jenna Bush story as news do so solely because right-wing attack dogs would have had a field day with similar news about Chelsea Clinton. That reasoning is logically and morally corrupt, but it’s amazingly prevalent.

One yearns for absolute standards: that the private life of a public figure is either always news or it’s never news. But that’s impossible. The stench of hypocrisy will always draw the media’s attention, and it should. I’ve found myself thinking a lot about Salon’s much-criticized decision to run the story of Henry Hyde’s extramarital affair as Hyde, a harsh Clinton critic, was set to head the House impeachment committee. I was torn at the time, and still am, a little. But the almost exact correspondence between what Clinton was being impeached for — and it was adultery after all, not lying about it — and Hyde’s own hidden past made it, in the end, a solid, defensible story. Sullivan, by contrast, has taken complex and contradictory stands on gay sexual politics, and, at any rate, isn’t standing in official judgment over anyone.

I’m torn, too, about the extent of the Jenna Bush coverage and at what point it becomes overkill. I’ve actually gone farther than many people and suggested her drinking may have something to tell us about her father, the president. Issues of character and judgment have always been the real questions about Bush, a relative political lightweight who got elected thanks to his promise to “change the tone” and “restore honor and dignity” to the Clinton-befouled White House. He got a pass on his own drinking, and even used his daughters as an excuse for not coming clean about his DUI. Jenna’s drinking is evidence that such a course was not only bad politically but perhaps bad personally, in that professionals always advise parents with alcohol problems to tell the truth about their drinking. On the other hand, I was once 19, and I cringe at the extent to which Jenna Bush has lost her privacy.

But then, we’re all on the verge of losing our privacy if Andrew Sullivan’s critics have their way. Maybe the scariest thing about their defense of outing Sullivan is the extent to which they insist he has no rights to privacy, especially when he’s been so foolish as to post personal information on the Internet. In that sense, they sound a little like Fleischer, as though the Internet is a dark and scary realm where you can’t complain about meeting dragons if you’re dumb enough to go there.

Of course, some of these same left-leaning zealots no doubt oppose corporate invasions of Internet privacy, and support the movement to limit attempts to capture and disseminate the information we reveal about ourselves on the Internet daily. That said, Sullivan and others probably have to accept that there is no privacy and anonymity on the Internet anymore — though Sullivan has paid a heavy price for not understanding, in time to protect himself, the extent to which the rules have changed.

What’s most striking is the lack of sadness on this last point. Privacy seems a little like oxygen to me, necessary for human life, and evidence of its ever-shrinking dimensions is a little like the hole in the ozone layer, ominous and depressing. Payback feels good at the time, but in the end it really is a bitch. For all of us.