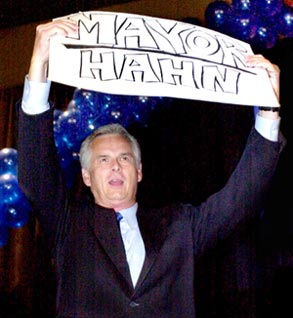

For all of the talk about the promise of the new Los Angeles — with its new surge of Latino voters poised to elect the city’s first Latino mayor in more than 100 years — city attorney Jimmy Hahn’s victory in the all-Democratic mayor’s race Tuesday over former Assembly Speaker Antonio Villaraigosa was a refresher course in some old political lessons.

Lesson No. 1: Negative campaign ads work.

The postmortems on this race will all mention the TV spot run by the Hahn campaign focusing on a letter Villaraigosa sent to President Clinton in 1996 on behalf of cocaine trafficker Carlos Vignali. The spot was used by Hahn to show that Villaraigosa was soft on crime and that he could not be trusted. Villaraigosa countered by comparing Hahn to L.A.’s racist mayor from the late 1960s and early ’70s, Sam Yorty, claiming the ad, which featured images of a smoking crack pipe, played to racial stereotypes and fed into an attempt by Hahn to create a “climate of fear.” The pro-Villaraigosa L.A. Weekly picked up on Villaraigosa’s critique, referring to Hahn as the “Son of Sam.”

Hahn stood by the ad, claiming that it was Villaraigosa, in his charges that Hahn’s ads were negative, who was actually the candidate resorting to dirty campaign tactics. Villaraigosa, the logic circles, is the one who “went negative” by claiming Hahn “went negative,” and so on, and so on.

The spot was perhaps the key turning point in a race Villaraigosa once led. In the runoff’s race to the center, Hahn’s ad helped cement the image of Villaraigosa as the liberal in a race that was actually a battle of two liberal Democrats. Though the city has moved significantly to the left since first electing Republican Richard Riordan eight years ago — thanks to increased labor activity and new Latino voters that have sent Republican registration down in L.A. from 26 percent in 1993 to 20 percent today — Republicans still constitute a key swing vote in the city. The Times poll showed that most of the votes from the May primary’s third-place finisher, Republican developer Steve Soboroff, went to Hahn.

It was those Republican swing voters who seem to have been most moved by Hahn’s portrait of Villaraigosa as a soft-on-crime liberal. Among Hahn voters, 30 percent of them said crime was their top issue, only slightly behind education and the economy. And despite Riordan’s endorsement of Villaraigosa, Republicans voted more than 3-1 for Hahn, comprising 28 percent of Hahn’s total votes.

Lesson No. 2: Race still matters.

Many of us who write about politics in California want to believe that California is the great American exception; that because we live in state where no one ethnic group makes up more than 50 percent of the population, this means we are somehow beyond race in our politics. But looking at the exit polls from Tuesday’s race shows this is simply not the case.

Latinos constituted a record-breaking 25 percent of the Los Angeles electorate Tuesday, turning out in record numbers to vote for one of their own. According to the Times exit poll numbers, Latinos voted for Villaraigosa 4-1 over Hahn.

Similarly, blacks came out to cast their votes for Hahn, whose late father, Kenny, was a supervisor in South Los Angeles for four decades, and was revered as a hero. African-Americans made up just over 18 percent of the electorate Tuesday, with three-fourths of their vote going to Hahn.

But it is true that while race is part of the story, it is not the entire story. Much of the national media attention on the race focused on the black-vs.-brown plot because it’s sexy. But it is really a more traditional, economic, issue-based coalition that catapulted Hahn to victory, with Hahn positioning himself as less evil for L.A. moderates and conservatives. Hahn’s key to victory was picking up voters who had voted for Soboroff or conservative City Councilman Joel Wachs in the primary. Focusing on issues like crime, and fears that Villaraigosa was too liberal, created that opening for Hahn. And though Tuesday’s mayoral vote was something of a Hobson’s choice for many L.A. Republicans, Villaraigosa’s call for a living wage for city workers and his criticism of police chief Bernard Parks — and of course the Hahn ad — helped make Hahn the more palatable candidate.

Hahn’s strength in the black community had nothing to do with the campaign he ran in the runoff — that of a tough-on-crime centrist — and everything to do with who he was — Kenny’s boy. But had Villaraigosa been in the runoff against, say, Soboroff, blacks would have likely been solidly behind Villaraigosa. Blacks supported Hahn because of who he was, unlike the Republicans who voted for Hahn because of who he wasn’t.

As it turned out, the race in Los Angeles shared striking similarities to two recent mayoral races in Northern California — the election of Jerry Brown in Oakland in 1998 and San Francisco Mayor Willie Brown’s reelection victory in 1999.

Like Hahn, both Browns are liberal Democrats who found themselves outflanked by challengers on their left. In the case of Willie Brown, the challenge came from Supervisor Tom Ammiano. Brown even earned the endorsement of the San Francisco Republican Party in the runoff against Ammiano, whose coalition of gays, progressives and myriad enemies of the incumbent mayor propelled Ammiano into the runoff as a write-in candidate, but left him short in the runoff.

As with Ammiano, Villaraigosa’s progressive coalition of union members and Westside liberals wasn’t enough to put him over the top. Though he had key endorsements from Riordan, and Univision owner Jerry Perenchio, both Republicans, as well as billionaire Eli Broad, Villaraigosa became the candidate of organized labor, thanks to a key endorsement from the County Federation of Labor. County Fed political director Martin Ludlow said in April that Villaraigosa’s election was the most critical municipal election for the national labor movement. Interestingly, the Times poll showed a virtual split in the actual union vote in Tuesday’s runoff. But with big financial backing from the county’s largest labor organization, and with his own background as a former labor organizer, it was Villaraigosa who was tagged with the union label that helped draw Republicans to Hahn.

In fact, some writers, such as Gregory Rodriguez, have made the case that Villaraigosa was, in a sense, a labor candidate first and a Latino candidate second.

“If L.A.’s labor-left-Latino alliance catapults Antonio Villaraigosa into City Hall this week, it will represent the culmination of a generation-old activist dream rather than a vision of the Latino American political future,” Rodriguez wrote in the Los Angeles Times Sunday. “In backing activist candidates, L.A. Latinos may be going against a broader tide toward more professional, business-oriented Mexican American politicians,” such as former San Antonio Mayor Henry Cisneros, newly elected San Antonio Mayor Ed Garza and California Lt. Gov. Cruz Bustamante.

Indeed, while moderate Latinos have enjoyed increasing success in larger political arenas, Villaraigosa’s defeat marks a small trend for Latino progressives running for higher office. The last time unions rallied behind a Latino candidate in a California mayoral election, the result was similar to the result in Los Angeles Tuesday night.

That was the case of Oakland City Councilman and former union organizer Ignacio de la Fuente, who, like Villaraigosa, was defeated by a white politician who had huge support from the city’s African-American community — Jerry Brown.

Certainly, the de la Fuente/Villaraigosa comparison is not a perfect one. De la Fuente faced a celebrity former governor who crushed the rest of the field. And the councilman had his own problems to deal with, most significantly his role in a botched deal to bring the Raiders back to Oakland from Los Angeles that ended up costing local taxpayers millions of dollars. But it was Brown, positioned as a moderate, who was able to build a multiethnic coalition that carried him to victory.

Villaraigosa was supposed to replicate that kind of coalition. Throughout the campaign, the former Assembly speaker claimed the mantle of the racial bridge-building of Tom Bradley. But the differences between Bradley and Villaraigosa are instructive in understanding why Villaraigosa came up short against Hahn. Bradley was a former cop, a moderate whom centrist voters could feel comfortable with. Villaraigosa, a former union organizer, was ultimately dogged by the liberal label. Thirty-five percent of all Hahn voters said Villaraigosa was too liberal, or was not interested in serving all parts of the city.

Villaraigosa’s success in the primary was due largely to the fact that he was the union candidate, yet he proved to be the worst sort of union candidate — one who was tarred by the connection but apparently wasn’t even able to rely on the support of that base.

Which brings us to Lesson No. 3: Above all else, Jimmy Hahn’s victory over Villaraigosa shows that while Los Angeles was ready to take a step to the left, it didn’t want to make the jump. In the end, the candidate in the center was the one left standing.