It says so much that is damning about Steven Spielberg’s “A.I.” that the best thing in it is Jude Law’s Gigolo Joe, a character that serves no useful narrative function. You’ve probably heard or gathered that Joe is a “mecha,” a robot, a machine that has specialized in bringing sexual consolation or adventure to pale and forlorn women who have nearly forgotten the state of rapture. For in the vague future time of “A.I.,” just as the oceans have come up, so the libido of most people (the personality level, even) seems to have gone down.

So Joe can crack a joke and a grin as fast as his thumb-flicking motion can turn on a period crooner to assist in his seduction. You can only imagine the great whirring thing, the Dyno-rod of delight that he keeps beneath his black leather coat. If Buñuel had made “A.I.” you might have had a charming shot of Joe oiling his instrument, or rubbing pine tar on it.

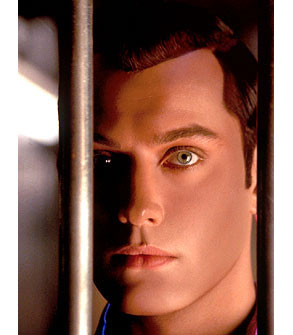

Gigolo Joe is a terrific idea, but then we get everything that Law brings to the part. When I ask if there’s anyone on-screen these days so thoroughly alert and alive, you may begin to feel the irony barely picked up by Spielberg: that mecha Joe is so much more compelling than the real people (the “orgas”) who look down on him. And it isn’t just that Joe can get an endless hard-on to entertain the ladies, it’s more that he is all hard-on — a shiny, freshly painted puppet, Punch’s naughty boy, with a crest of hair that is the hardest nut you’ve seen (or felt in your soft parts) since Bogart’s toupee.

It’s plain to see that this gigolo is acting like a mecha to be a better turn-on, to conjure up fantasies of mechanical endurance. There’s a wealth of wit and character within him, so much sparkling originality and caprice — it left me realizing that, long ago, in “American Gigolo,” Richard Gere had been the true robot prototype, numb to feelings or ideas, just obsessed with matching the right shirt and tie.

But here’s the intriguing point: In so many modern movies, there is the creeping sensation that real-life men and women don’t have it anymore, that they’re weary of sex and all the emotional turmoil that goes with it. Whereas Joe has the happy optimism of someone who has never met a girl he wouldn’t like to fuck. But why is it that our imagination now so readily attributes a kind of sexual vitality to robots, androids or machines?

All the woeful sentimentality of “A.I.” suggests a wish on Spielberg’s part to see the mechas as deprived, underprivileged outcasts. Yet somehow there’s a subtextual energy, a curiosity in us, pulling the opposite way and saying how sweet it might be to be with a machine (call it a pacemaker, a simple little trigger mechanism such as the one that guards Dick Cheney for us all). Just think what a dazzling satire “A.I.” might have been if the robots (even the primitive models) turned out to be kinder people, more trustworthy, better problem-solvers and headier lays than the self-righteous ghosts who can claim organic material.

Why is this? I think it’s because of something that Spielberg never quite grasps — that, for a hundred years now, we have had a species of robot to play with. They are called the people in movies — very lifelike, very pretty, brimmingly sexy, unaging and very obedient to our dreaming urges. Is it any wonder if we prefer these mechas to our sad, failed selves?