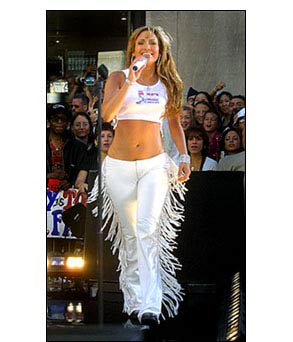

The instant word hit the street that actress-singer Jennifer Lopez had used a racial epithet in one version of her new single, “I’m real,” black protesters hit the barricades. The fact that Lopez is of Puerto Rican ancestry made no difference. The protesters demanded that Lopez apologize, and that Epic Records pull the record.

The Lopez flap has by now become part of a well-worn pattern. A non-black celebrity, politician or sports figure slips or intentionally uses a racially-offensive word or makes any other racist reference. They immediately hear about it from outraged blacks. Cincinnati Reds owner Marge Schott, sports personalities Al Campanis, Jimmy “the Greek” Snyder, former Atlanta Braves star John Rocker, author Pat Conroy and California Lt. Gov. Cruz Bustamante were publicly crucified for making racially insensitive remarks or for using the “N” word. They quickly offer their mea culpas, and they hope and pray that their careers aren’t ruined.

The problem is that many of the blacks who rage at Lopez, and others who casually toss around racially loaded words, do not unleash the same fury on blacks who use the same words. In the crossover world of hip-hop culture that Lopez hails from, the use of racially offensive words has become a high art. Lopez has certainly heard legions of black comedians and rappers punctuate every line in their rap lyrics and comedy lines with those words, especially the “N” word, ad nauseam. In fact, we don’t have to guess about whether her ears were sullied by the word. Her scandal-plagued ex-soulmate and rap kingpin, Sean “Puff Daddy” Combs, once led a concert crowd in the chant “F… you Nig…” And fellow rapper, Ja Rule, who’s black, co-wrote Lopez’s controversial song, and does a duet with the singer on the cut.

Lopez also has certainly read or heard of the many black writers, and filmmakers who go through lengthy gyrations to justify using the word. Their rationale boils down to this: The more a black person uses the “N” word, the less offensive it becomes. They claim that they are cleansing the word of its negative connotations so that racists can no longer use it to hurt blacks.

Comedian-turned-activist Dick Gregory had the same idea some years ago when he titled his autobiography with this racial epithet. Gregory has since denounced the use of the word — and those blacks who use it. Many blacks say they use the “N” word endearingly or affectionately. Still, others are defiant. They say they don’t care what a white person calls them, words can’t harm them.

But the black “N” word defenders miss the point. Words are not value-neutral. They express concepts and ideas. Words reflect society’s standards. If color-phobia is one of its most powerful standards, then emotionally laden racist words easily reinforce and perpetuate stereotypes. And a hyper-racially-charged word such as the “N” word does precisely that. It is the most hurtful and enduring symbol of racial oppression. It has a grotesque history.

Before World War I, many major magazines and newspapers reinforced the status of blacks as racial pariahs by routinely using racially offensive words to describe them. The NAACP and black newspaper editors waged vocal campaigns against this racist stereotyping. Racially offensive words have also left psychological scars on past generations of black children whom American society treated like racial untouchables. Novelist Richard Wright in his memorable essay, “The Ethics of Living Jim Crow,” remembers the time he accepted a ride from a “friendly” white man. When the man offered him a drink of whiskey, Wright politely said, “Oh, no.” The man punched him hard in the face and called him a racial epithet. The pain from the blow would pass but, the pain from the word stayed with him forever.

Comedian Richard Pryor understood this. At one time the irreverent Pryor had practically made a career out of using profanity and racially offensive words, particularly the “N” word, in his routines. But then he had an epiphany. He told a concert audience that he would not use the “N” word, or other racially offensive words again. The audience was stunned. Pryor softly explained that these words were profane and disrespectful. He was dropping them because he had too much pride in blacks and himself. The audience applauded. Pryor was as good as his word.

Those blacks who aim intense fire at Lopez should go rent the tape of that concert. They will see why they must aim the same fire at black entertainers who make a fetish out of using racially degrading words as they do at Lopez.