It's the turn of the century in the Old West. Two young men are relaxing in a cathouse, amused to hear a helpless sheriff trying to raise a posse to go after them in the street outside. They are safe, you see, protected by their own cool attitude and the way they are in another, later time, looking back on the Old West as if it were a picture postcard -- quaint. One of them elects to move on from the cathouse, to find a more genuine woman.

Then, at twilight, in some mountain town, we see a young woman in white walking home to her small wooden house. She goes in, lights the lamp and prepares to take off her clothes. But then -- as if she had felt our presence, gently watching her -- she knows there is a man inside her house, sitting in the dark, observing her. She freezes in the classic stance of a woman who anticipates rape.

The man has drawn his gun, and we have seen earlier how very deft he is with a gun. He indicates with it that she is to continue the disrobing. You feel the air being sucked out of her cabin by the tension. She takes off the long petticoats, revealing shorter ones. No need to stop there, he implies. The muzzle of his gun directs her nervous fingers to the little bows that hold her nakedness back. He tells her to let down her long brown hair, and shake it -- just like an actress who has come on a television talk show and shakes her hair to lay claim to the erotic space around her.

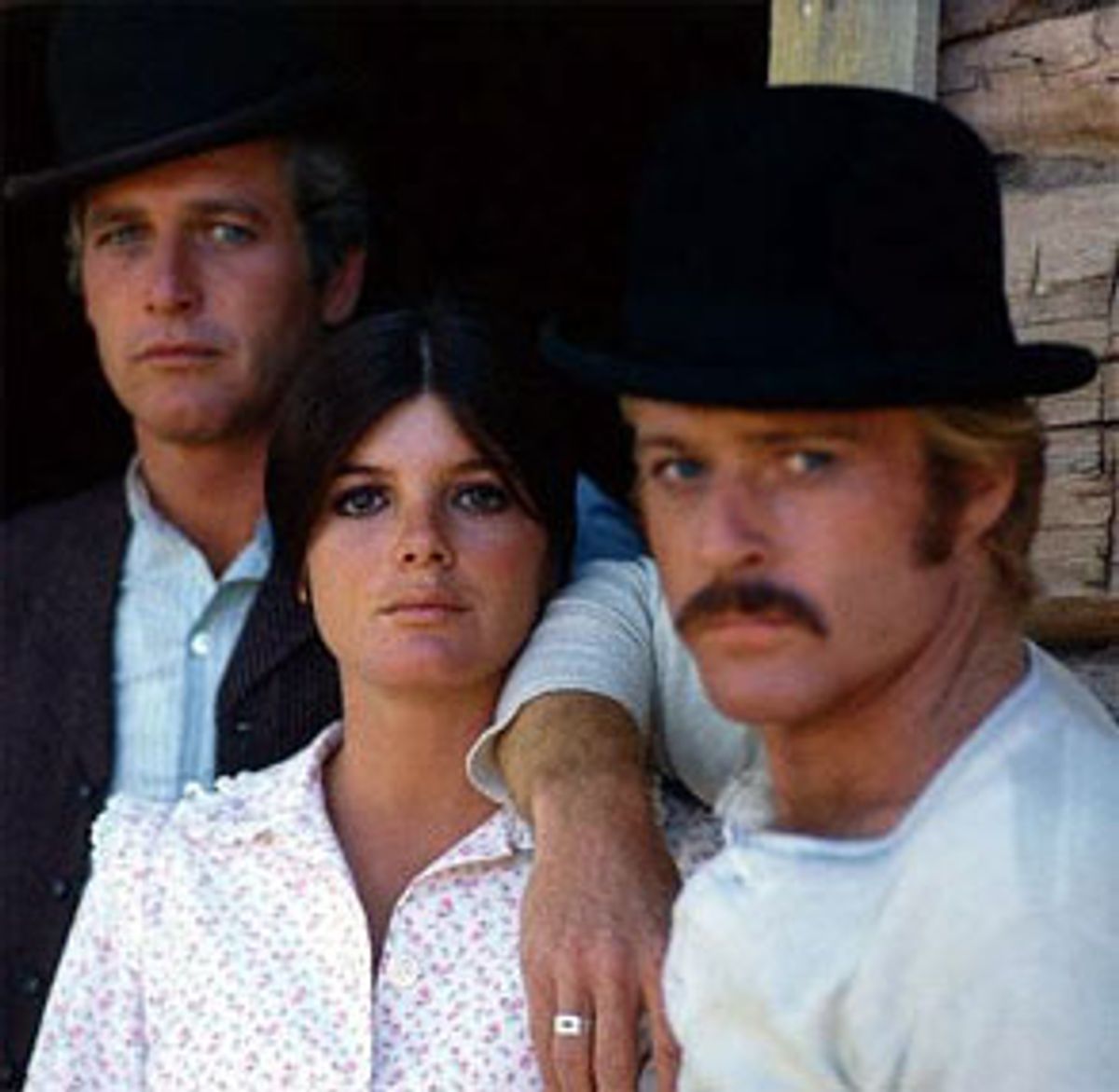

Turn of the century? She stands there, with only the dark of incoming night hiding her breasts from us. She looks so very like that very '60s, Californian actress, Katharine Ross, the one with the unmistakable 1960s mouth, modeling for some kind of advertisement -- it might be coffee or leather goods -- in an 1890s setting.

The man goes up to her. He slips his hand into the lovely ajar place where her half-slip is open, and she falls upon him with some such line as can't he ever be there on time.

She knew he'd be there; she'd given up walking around the town, till it was dark, waiting for him to come. He knew she knew. It is a game they play, these very cool perfect lovers, stepping in and out of the past and the prospect of rape, as if such things were just their flimsy clothes.

Yes, it's "Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid," and it's a cute scene still, undeniably sexy (or at least, sexy at the level fulfilled by Ross and Redford), in a movie where modern actors and writers seem to be watching a silent western, joining in and talking back to it, reassessing it for their smart superiority.

It's not quite a matter of realism, of the turn-of-the-century codes being exposed to harsh truths. If it were, then the next morning, when Butch arrives on his new bicycle, Sundance would silently slip out of the warm bed and Butch would take up residence with an Etta who never complains, but knows her place. In fact, while Sundance dozes still, Butch takes Etta out on a ride -- he has her on the crossbars, if you like. That's where "Raindrops Keep Falling On [Our] Head," and that's pretty well where the western collapsed and spoof, parody and pastiche began.

No matter that it was 1969, the picture didn't quite want to test its audience with the notion that two bold hombres or two big stars might share Etta in the way they share a tin cup. There was a kind of daring in the film that didn't really come from any particular filmmaker. So the movie wasn't quite smart enough to show that in keeping with the mockery of the western, Butch and Sundance are gay saddle tramps, companions in the dust, who just keep an Etta around to ward off questions.

So the scene, and the film, play today with so many extra fascinating subtexts, and you wonder whether some studio people crossed their fingers in 1969 and hoped that Redford and Newman (the money, after all) wouldn't object to the sneaky little ideas and thrills that come crawling through the holes whenever you start to take a grand old building like the western down.

Or maybe they were in on it.

Shares