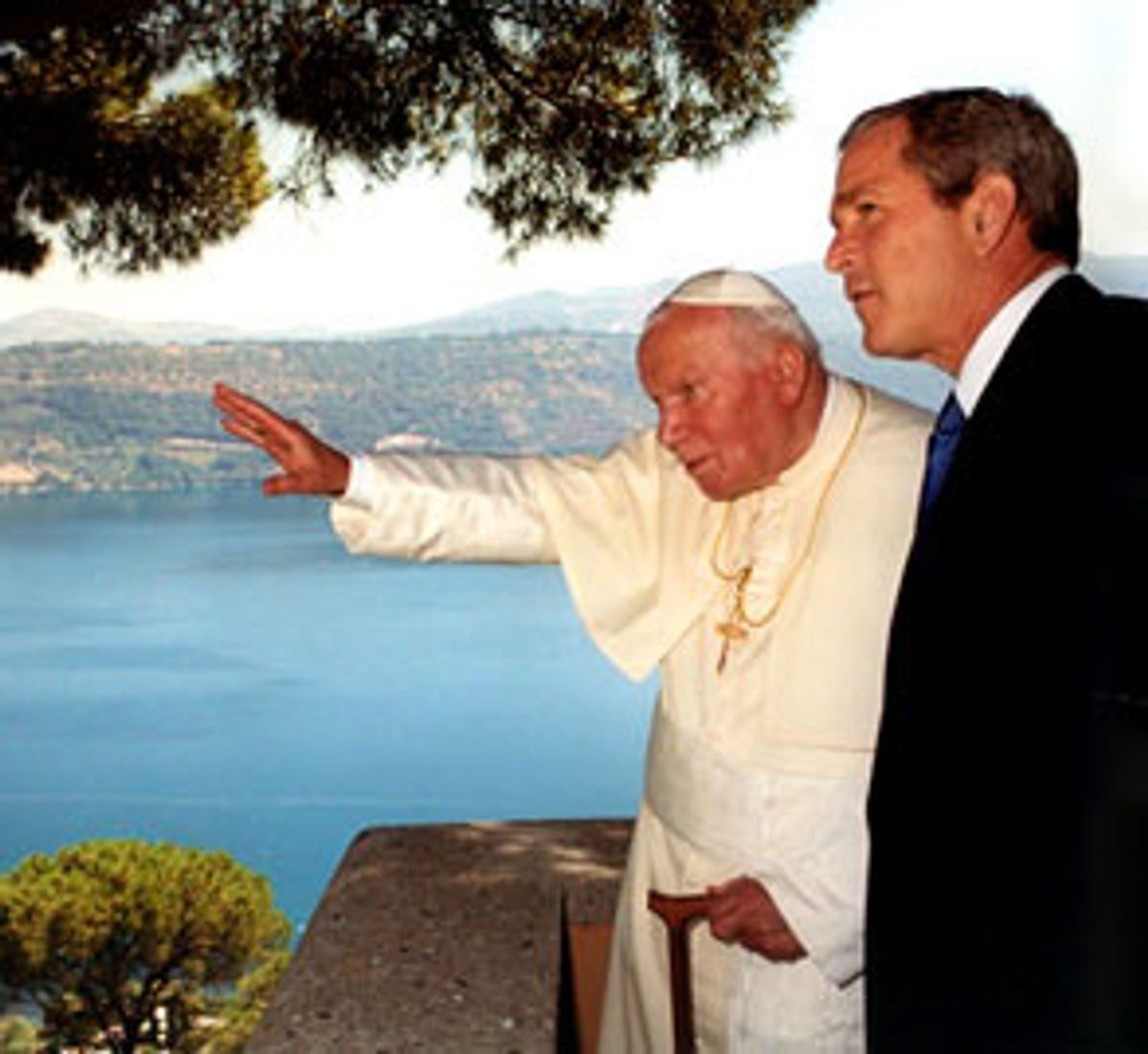

When Pope John Paul II warned President Bush about the "evils" of stem cell research last week, he heightened the already extreme tension surrounding the administration's protracted decision on whether to federally fund such research. Regardless of the president's final decision on stem cells, the perception that Bush is taking the pope's advice into account laid the foundation for a key component of the president's reelection strategy: wooing the nation's Roman Catholic vote.

Both Bush's meeting with the pope and his caution on the stem cell decision are clearly part of his ongoing effort to court the country's 44 million Catholic voters. Those individual moves won't necessarily pay off politically -- the majority of American Catholics disagree with the pope on many issues, from the death penalty to abortion rights, and they support stem cell research -- but the overall effort makes some political sense. White Catholics have been a key swing constituency in American presidential politics for the past 20 years. Historically, it has always helped to have the Catholics on your side on Election Day: They have voted with the winner in the last eight presidential elections and 11 of the last 12.

"If you were sitting in on a White House strategy session, you'd probably hear Karl Rove say the 2000 election was essentially a tie, and in 2004, we need at least a narrow win," says John Green, a political scientist at the University of Akron who has monitored Catholic voting patterns. "'Where can we move people?' One of the first groups they have to look at is white Catholics."

In fact, Rove has been the brains behind the administration's efforts to woo Catholics. But Bush can't play to a monolithic Catholic voting bloc, because there isn't one. In fact, many political analysts scoff at the notion of a "Catholic vote."

"Let us begin with this simple fact: there is no such thing as the Catholic vote," writes Anna Quindlen in a recent Newsweek column. "Once upon a time there was something like it ... American Catholics are no longer uniformly struggling immigrants, they no longer uniformly attend closely to the pronouncements of the church hierarchy and they do not uniformly vote as a bloc. There has been nothing uniform about most of our lives since parochial school."

For years Catholics were a reliable part of the Democratic New Deal coalition. Clustered in the Northeast and Midwest, disproportionately working class, often the victims of discrimination by the WASP elite, as many as 70 percent of Catholics voted Democratic.

Today, there are several different Catholic votes -- white ethnic Catholics from the Midwest and Northeast, who have trended slightly Republican, and a new generation of Hispanic Catholic voters, mostly in the Southwest, who tend to favor Democrats. A smaller group of black Catholics continues to be a reliable Democratic constituency. And alongside racial and ethnic divisions, pollsters see other splits in the Catholic bloc, most notably a relatively new division between churchgoing Catholics, who are predictably more conservative, and nonobservant Catholics, who tend to be more liberal.

"Now there is a core Democratic constituency and a core Republican constituency among Catholics," says Green, and both parties are courting the Catholics in the middle.

The Democrats may have the best weapon for wooing Catholics if they nominate any one of the four Catholic Dems -- Sens. John Kerry, D-Mass., Tom Daschle, D-S.D., Christopher Dodd, D-Conn., and Gov. Gray Davis of California -- frequently mentioned as presidential nominees in 2004.

"That's interesting," says Deal Hudson, editor and publisher of Crisis Magazine, who calls himself "an informal advisor" to the White House on Catholic outreach and issues, even though calls to the Republican National Committee seeking comment on Catholic issues were funneled to Hudson.

Bush has courted Catholics aggressively, particularly those who "see life as a defining issue," Hudson says. But it isn't just his pro-life stance that has appealed to Catholics. Hudson says Bush's "compassionate conservative" pitch was partially tailored to Catholic voters.

"Republicans had to convince people that they really did care about the less fortunate," says Hudson. "There has been a perception that the Republican Party is the party of the rich and powerful. That's an issue that has to continue to be addressed by the party."

So when Bush went looking for a place to unveil his proposal to involve religious groups in government-sponsored social welfare programs, he chose a Catholic University, Notre Dame, and quoted Catholic left-winger Dorothy Day. (Day's family wasn't swayed.) And when he looked for someone to spearhead the initiative, he chose a Roman Catholic from a key swing state, John DiIulio of Pennsylvania.

More recently the focus on Catholics can be seen not only in Bush's meeting with the pope and his agonizing over his stem cell research policy but in the surprising proposal to grant amnesty to most of the 3 million Mexicans living illegally in the United States. A panel of Bush Cabinet officers, headed by Secretary of State Colin Powell and Attorney General John Ashcroft, recommended that Bush endorse the amnesty plan, to the howls of more nativist Republicans. Clearly the move was designed to shore up support among Latinos, who are mostly Catholic though increasingly joining evangelical Protestant sects.

"We got 35 percent of the Hispanic vote" in the last election, RNC spokesman Trent Duffy recently told Insight Magazine. "If we don't get that up to 38 or 40 percent, it's all over."

Bush failed to receive even 30 percent of the Latino vote in California, a state where the memories of Gov. Pete Wilson's anti-immigrant campaign remain fresh. But some California watchers assume that as the state's new immigrants assimilate, an increasing portion of that bloc will vote Republican, like their white Catholic counterparts on the other side of the country.

Many traditional Catholic Democrats were first- or second-generation Americans, most of them blue-collar Irish, Italians or Slavs in the Midwest and Northeast. But in a traditional American pattern, as discrimination waned assimilation took hold. And with that, Catholics became more conservative. Throughout the 1970s, Republicans began to make inroads among Catholic voters as the hostilities between Catholics and Protestants diminished. This trend crystallized in 1980 with the election of Ronald Reagan. Reagan carried 50 percent of the Catholic vote in 1980 while winning 51 percent of the national popular vote. In 1984 he was reelected with 54 percent of the Catholic vote.

Yet even now, Green says, as Catholics have left the Democratic Party, Republicans haven't necessarily inherited their support. "Many of them remain independent," Green says. "Catholics have moved much more slowly in a Republican direction."

Over the last decade, a new divergence among Catholics has materialized that's giving some hope to the GOP -- a division between observant and secular Catholics that's evident in the voting booth. Before the 1990s, there was no discernible difference in the political behavior of Catholics who went to Mass and those who didn't, says Green. But that has begun to change. This rift was seen in the last election, says Green. According to a University of Akron survey from earlier this year, Al Gore won 50 percent of the overall Catholic vote, including 59 percent of the less observant white Catholic vote. Bush, meanwhile, won 47 percent of the overall Catholic vote, but took 57 percent of the vote from more observant white Catholics.

Hudson says the trend of observant Catholics voting Republican is not about assimilation but the opposite: Observant Catholics feel increasingly comfortable voicing their pro-life values. "I would say assimilation is the one reason so many Catholics are comfortable in the Democratic Party," he says. "For Catholics to own up to the fact they're pro-life is not an assimilating thing to do. It's really another step. They're saying, 'I've made it but I can be comfortable being pro-life,' which is against the dominant culture."

The Bush team is hoping to bring churchgoing Catholics into line with Protestant evangelicals, 84 percent of whom voted for Bush in the last election. Despite the administration's aggressive courting of religious Catholics, increasing the GOP vote totals among those voters will be an uphill battle. "These things don't change overnight," says Green. "And there is still a long historical tradition linking Catholics and the Democratic Party. But that could change in another generation or so."

Even some relatively liberal Democrats think the new independence of Catholics is a good thing. "The days are gone when taking Communion and pulling the Democratic lever were the outward signs of a good Catholic," writes E.J. Dionne, a Washington Post columnist and research fellow at the Brookings Institution.

But in reality, this new crack in the Catholic bloc, Green says, could bring the days of the Catholic swing vote to an end, and ultimately decrease attention to Catholic votes. "We're seeing continued polarization among white Catholics," he says. "You're seeing a growth of conservative Catholics, and a simultaneous growth of more liberal Catholics that are Democratic. You can really see this in the church. You have conservative elements of the clergy pushing opposition to abortion and issues like that. Meanwhile, liberal priests stress social welfare, that kind of thing. That effect is a polarization."

The wild card, of course, is whether the Democratic Party winds up nominating a Catholic for president. No Catholic has appeared at the of the national ticket of a major political party since John Kennedy in 1960. That year, Kennedy won 83 percent of the Catholic vote, edging out Richard Nixon in one of the closest presidential elections in American history. Though Catholic identity has waned in terms of predicting political behavior, a Catholic on the ticket could rejuvenate it.

But not necessarily. With Joe Lieberman on the ticket, Al Gore received 79 percent of the Jewish vote, according to numbers from the American-Israeli Cooperative Enterprise. That is virtually identical to the 78 percent Bill Clinton received in 1992 and 1996.

The difference here is that Jews are already reliably Democratic. Green says it remains to be seen if a Catholic on the Democratic ticket can temporarily stop the trend of Catholics moving away from the party.

"The new partisan competition makes the Catholic vote interesting," writes Dionne. "As a Catholic, I'd like to think it could also be useful, and that Catholics might challenge both parties. Catholic Democrats might suggest that social justice and a concern for the health of family life go together. And Catholic Republicans could argue that acting on behalf of society's least fortunate is not just good politics, but the right thing to do."

Shares