According to the documentary “Stanley Kubrick: A Life in Pictures,” Kubrick used to say that he’d string together a few good scenes and in the end he’d come out with a movie. You can see that formula in Francis Ford Coppola’s “Apocalypse Now.” Or at least that’s the way I remembered it.

First, there’s Captain Willard (Martin Sheen) doing drunken Kung Fu in his Saigon hotel room. Then there’s a dozen or so helicopters in attack formation and Lt. Col. Kilgore (Robert Duvall) strutting along a beach, checking out the waves, oblivious to the mortar shells exploding at his boots. Then come the Playboy bunnies prancing across stage. Next parachute flares and tracer fire light up the night sky at a devastated bridge. And then we finally meet creepy Colonel Kurtz (Marlon Brando) in his riverfront death palace. “The End.” The end. Credits.

But watching the newly restored “Apocalypse Now Redux,” which features new scenes and nearly an hour of additional material cut from the first version, reminded me that the film is far more than just a string of jewels. There’s a narrative wire that connects each of the movie’s precious baubles, a force pulling Willard and his boat upstream to their deadly rendezvous with Colonel Kurtz. And the dialogue and the narration — all those great lines about “napalm in the morning” and “handing out speeding tickets at the Indy 500” — are the brilliant light glinting off the facets.

The most important thing about the most recent version of the film — the third, as far as I can tell — is that it’s in theaters, playing on huge screens with booming sound systems. The movie is so big and so nuanced in its druggy delirium that it gets lost on a television, especially without a widescreen aspect ratio.

The second most important thing is that Coppola and his editor, Walter Murch, have restored, re-edited and remixed the entire film. The new print looks great; save a short scene with a bunch of dust flecks about two-thirds of the way in, it was flawless. Cinematographer Vittorio Storaro’s daylight skies are oddly yellowish, and the jungle scenes are a sort of muted green. This Vietnam isn’t a lush tropical paradise. The most vibrant, saturated colors you see are in blood and fire.

The bait luring moviegoers back into the theaters, 22 years after the movie was released in 1979, is several scenes that were cut from the first print of the movie. There are two entirely new scenes: the other additions are material previously left off the end of scenes or cut out of transitions. And in one place a scene was cut from the original and placed further along in the story.

For the most part, the new material brings Coppola’s sometimes murky, sometimes crystalline vision into clearer focus. (If you haven’t seen the new version yet, be aware that the remainder of this review contains several spoilers.) Except for the absence of the scene where Lance (Sam Bottoms) water-skies behind the boat and Clean (Larry Fishburne) hips out to “Satisfaction” (it’s added later, after the USO show), the new movie plays scene-for-scene exactly as the original until the end of Kilgore’s famed Air Calvary helicopter raid. The helicopter scene is still every bit as spectacular as the original, with all those gunships zooming in on a well-guarded beachfront. It’s a thrilling sequence that manages to pump you up on Kilgore’s bravado and then slam your head into the armrest when the movie closes in on the real human devastation that the attack wreaks.

Kilgore, remember, is in charge of escorting Willard through the Delta. Instead of taking an easier route, he chooses a well-protected point because there’s an offshore break and he wants to watch Lance, a famous surfer accompanying Willard upriver, ride the waves. The raid is fast and devastating. Kilgore loses three helicopters and several men to the effort. “If that’s how Kilgore fought the war,” says Willard, “I was beginning to wonder what they had against Kurtz.”

The scene used to end with Kilgore on the beach, inhaling the smell of napalm. Now, we find out that the napalm attack blows out the waves. For some reason — maybe to impress his new boatmates, maybe to piss off the Lt. Colonel — Willard swipes Kilgore’s surfboard.

That cuts to the scene where Chef goes into the jungle for mangos, which now begins with the boat crew hiding out under a leafy tree while Kilgore patrols the river searching for the board. It’s a fun new bit, and it seamlessly gets us from the beach into the river, while establishing a little camaraderie among Willard and the guys who will boat him upstream. At the same time, it’s a jarringly lighthearted gag to follow such a disturbing battle.

While waiting for Kilgore’s patrol to pass, Chief (Albert Hall) asks Willard where they’re going, and whether or not he likes hot zones. Willard doesn’t answer either question. In the narration, however, he says that you “never get a chance to know who you are at some factory in Ohio.”

I think that’s the first clue to what Coppola is trying to do with this version of the film, and what he might have been trying to get at with “Apocalypse Now” all along. Willard is all of us, an equivocal Everyman sent up a river to find some sort of truth — or at least an absence of lies. But to do that he must simultaneously try to find out who he is — and who Kurtz is. He can’t tell one story without the other, he says in the beginning. His quest involves an almost Shakespearean collision of dualities: good/evil, love/hate, win/lose, rational/irrational, soft/hard, friend/enemy, South Vietnamese Army/North Vietnamese Army, soldier/assassin, Willard/Kurtz.

At the end of the film, Willard is going to find out what Kurtz knows, which is that the truth exists in the middle of those dualities — that the truth is both sides at the same time. Perhaps this means that there is no truth at all. This dark revelation comes at the end of the picture, and the biggest criticism of “Apocalypse Now,” one delivered when it opened and repeated today, is that the film falls apart at the end. “Muddled” is the word most often used to explain the final scenes.

Insofar as this is true, it’s partly because Coppola is reaching for so much. If he had wanted to simply embroider a duality theme he could have remade Joseph Conrad’s “Heart of Darkness” in the Congo where the story originally took place. But Coppola sets the film in Vietnam, during the war, so that he could get at several other truths, or at least ask other questions. Coppola wants to point out that the war is mad, and that the Americans had been partially pulled into madness, and that only by fully abandoning themselves to madness, to Kurtz’s amoral void — by becoming “a snail sliding across a razor’s edge,” in his words — could we have actually won. But it would have been a victory at too high a price.

I think “Apocalypse Now Redux” works better at the end now because it spells out the tension within Willard far more clearly than earlier versions did. Indeed, a new character actually goes as far as explaining Willard’s duality to him, in a scene I’ll get to in a minute.

The next new scene comes after the Playmate show. Clean is prattling on about Playboy bunnies, telling some story about a G.I. who became obsessed with Playboys. Lance goes water-skiing. Meanwhile, we hear Willard reading over some of Kurtz’s writing about winning the war — foreshadowing the manuscript that Willard will find at the compound (and echoing the writings of Conrad’s original Kurtz). The writings say that Kurtz could win the war with hardened troops. Committed troops. The writings also remind of us of Willard’s admiration for Charlie, who Willard says gets harder in the jungle, who considers cold rice and rat meat food R&R.

After the boat motors by a downed Red Cross helicopter the crew comes upon a shoddy little camp in the middle of a torrential downpour. We see the Playboy bunny helicopter on the landing pad. Willard steps out to investigate. He looks around for the camp’s commanding officer. The grunts tell him that he stepped on a landmine. “Who’s in charge?” asks Willard. “Don’t ask me,” says a G.I. (The same thing happens in the upcoming bridge scene.)

Willard sees Bill Graham, the promoter from the night before, motioning to him from the mouth of the tent. It turns out that Graham wants to make a deal to trade two barrels of diesel fuel for a little time with the Playmates. Willard happily tells the boat crew the good news. Chief stays behind to work on the boat.

Both Lance and Chef end up with Playmates. Lance paints his Playmate with camouflage make-up. Chef tries to transform his girl into another that he remembers from a centerfold. Meanwhile, the girls talk about being told to do things you don’t want to do and raising birds at Busch Gardens. They’re both terrible actresses, which Coppola probably knows.

But it’s hard to tell what Coppola is trying to do with the scene. We learn that the men don’t really care much about the individual girls, but that’s hardly a surprise — they exist in a world without any women. So are we supposed to equate the exploitative way these women are being used with the way that these soldiers are told to blindly follow orders? About the only conclusive thing the scene establishes is why Willard has to get out of the boat later on at the bridge to look for fuel. (Although you could imagine that Coppola has Willard ingratiate himself to his boatmates again so he’ll fall further in their estimation when he kills an injured civilian woman in the next scene.)

The biggest addition to the new version of the film comes after the firefight that kills Clean. The boat slowly motors up to what appears to be a dilapidated hotel on the banks of the river. Again, Willard steps off the boat. The crew hears a voice shout out in French. Chef, who is from Louisiana, answers it. The American crew is soon surrounded by a well organized, well armed unit of Frenchman wearing scarves and smoking cigarettes. They are accompanied by armed Vietnamese.

One of the Frenchmen says that Willard and crew are welcome. They step ashore and bury Clean in a formal military ceremony, draping his body with the boat’s tattered flag.

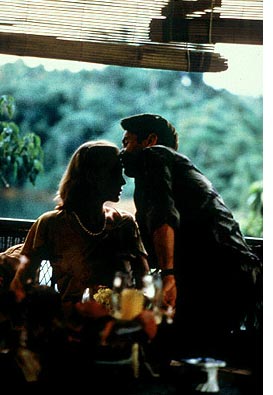

The crew is welcomed to a French rubber plantation run by several generations, who seem well entrenched and surrounded by the comforts of colonial goods, like elephant tusks and canopied beds. Willard notices a beautiful woman (Aurore Clement) gazing down upon him from a large veranda. The crew sits down to a formal dinner with the French, who are all dressed like extras in a Merchant-Ivory picture.

At dinner, the Frenchmen talk with Willard about the history of French colonialism in Vietnam and the origins of the American involvement in the war. “Why don’t you Americans learn from our mistakes?” one of them says, adding that he is fighting for his family while “you are fighting for the biggest nothing in history.”

The Frenchmen end up arguing about communism and socialism and soon only Willard and the woman from the veranda, a widow, remain. She invites him to join her for a cognac. He declines and says that he needs to get back to the boat. “The war will still be here tomorrow,” she says. We see exactly where this is going.

Sort of. The two talk for a while. Willard tells her that he will never go home. She puts him in bed and smokes him up with opium. She tells him that Willard, as a soldier, is like her husband. “There are two of you, don’t you see? One that kills, and one that loves … All that matters is that you are still alive.”

And that’s it. The scene is long and sluggish, and it slows down the movie right before we get to Kurtz (although it does give us some time to recover from Clean’s death before we have to watch Chief die). But it’s there for a reason. It further connects the film to Conrad’s novel, expressing the same ambivalent feelings toward colonialism (and reminding us of the historical origins of the war.) We’re supposed to admire these French for sticking to their guns, but at the same time, recognize that they are strange, anachronistic creatures — people who belong to another time.

The scene’s most important function, though, is that it makes clear the nature of the battle within Willard’s soul. “There are two of you, don’t you see?” the woman tells him. “One that kills, one that loves.” Those words resonate, reminding us of what the stakes are for Willard — and for us — as we go into the final scene with Kurtz.

We don’t get any more new material until Willard has been captured and locked up. Kurtz opens up a steel cage and sits down. He pulls out a stack of articles from Time magazine and begins to read out loud. As with the colonial scene, Kurtz delivers information that viewers probably didn’t need in 1979, when the war was still fresh in memory, but it’s nice to have here. Kurtz drops the magazines and tells Willard to read them. Kurtz says that Willard is free to move around the compound but that he will be shot if he tries to leave.

Willard, we know, hasn’t figured out what to do. Coppola’s lead character is morally precarious because he hasn’t picked one side or the other. “I took the mission. What else was I going to do,” he’s told us.

But what he’s done, as he’s moved up river, researching Kurtz all the way, is learned to admire a man who he’s been told is insane. Kurtz is effective. Kurtz has balls. Kurtz is doing a better job fighting the war than the U.S. government is doing.

When he gets there, however, he finds something else entirely. There are half-naked bodies hanging from trees. There are severed heads littered across the steps. Huge idols are fashioned after Kurtz. It smells like malaria and death.

Kurtz has gone insane, but he’s also perfectly sane. He’s ineffective as a military man, but effective in the war. He’s a warrior poet, says the war photographer played by Dennis Hopper. “He can be terrible, and he can be mean, and he can be right … The man is clear in his mind but his soul is mad.”

Kurtz is a self-appointed god — which by definition cannot exist. But he does, and as a god the only thing that he will not permit is judgment.

Presumably a few days later, the Dennis Hopper character talks to Willard about dialectics. “You can either love someone or you can hate someone,” he says. He says fractions are worthless. It’s all or nothing.

Then Kurtz goes into his famous speech about the ideal warriors. They are “men who are moral who are able to use their primordial instincts to kill without judgment. It’s judgment that kills us.”

“It is impossible to describe what is necessary to those who do not know what horror means,” he says.

We know he’s right, because of all the terrible things that we’ve seen, and all the terrible things that we know Willard’s seen. Now Willard, in a sense, becomes Kurtz — without judgment. He decides to kill Kurtz. Kurtz decides to be killed. Coppola, by intercutting the murder with a ritual sacrifice, is pointing out that it’s a murder in which everyone knows his role.

Here, finally, the terrible duality within Willard culminates in a bloody act — but one that resolves nothing. As the captain kills he is Willard, the moral, rational agent of civilization, but he is also murderous, instinctive Kurtz. He’s carrying out his mission, but he’s also carrying out the wishes and unspeakable dreams of Kurtz. He’s found his truth out there in the jungle, and it is a truth neither he nor we, the viewers, can draw any consolation from — but neither can we escape it. And everyone else is dead.