For the newly minted chairman of the suddenly influential Federal Communications Commission, it was a rare slip of the tongue.

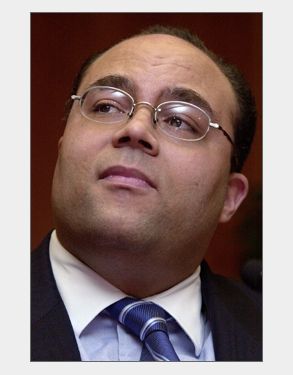

Testifying this spring before the House Commerce Committee’s Subcommittee on Telecommunications and the Internet, Michael Powell, the barrel-chested son of Secretary of State Colin Powell, was asked about current regulations that limit the number of individual television stations a broadcaster can own.

The regulations are in place to ensure that national network broadcasters such as NBC and ABC don’t buy up so many affiliate stations that local ownership becomes a thing of the past. Powell was also asked about the quarter-century-old regulation that forbids media companies from owning a TV station and a newspaper in the same city.

A silky-smooth public speaker, Powell is an exceptionally effective witness before Congress: quick as a whip yet with a soldier’s respect for authority. He is also an articulate free-market advocate who has previously made no secret of his distaste for the controversial rules, which prevent a broadcaster from owning stations that reach more than 35 percent of the general public. Pressed at the hearing by fellow deregulator-in-arms Rep. Cliff Stearns, R-Fla., Powell testified, “My effort is to always go back to my substantive points. Validate or eliminate. The 35 percent national ownership rule, if I remember correctly, is promulgated in the 1970s with an entirely different media environment than the present one, and should be validated if it has any merit at all in the current context.”

In other words, according to Powell, if the FCC can’t justify the ownership limits, which must be reviewed every two years, then they ought to be abolished. Period. But Powell was a little shaky on the facts. The law, as passed by Congress, says otherwise: it’s up to opponents of ownership caps to prove that the limits should be dropped, not the FCC. Powell also misspoke about dating the 35 percent figure back to the 1970s — ownership caps were actually raised from 25 to 35 percent in 1996.

But Powell’s questionable comments made no news that afternoon. Instead, committee members spent much of the day tipping their hats to one of Washington’s fastest-rising movers and shakers.

A would-be star in the Army until serious injuries from an end-over-end jeep accident on a German autobahn cut his military career short, in just a few short years Powell has hopped from a coveted court clerkship to a prestigious law firm to a chief of staff at the Department of Justice, all with the aid of A-list Beltway mentors from both major parties.

His personal bio is just as appealing. Married to his college sweetheart, Powell is a devoted family man who often gets to work before the sun comes up so he can spend time at night watching the Cartoon Network with his two young children.

And now he runs the FCC, and does so with unprecedented authority. “No FCC chairman, from Day One, has been more politically powerful, more well-connected and more knowledgeable,” says Reed Hundt, President Clinton’s first FCC chairman, “since perhaps Newton Minow during JFK’s administration.”

Michael Powell may need every last bit of that power and those connections, because his fast trip to the top has suddenly landed him in the hot seat. The ailing telecommunications sector that the FCC oversees is suffering its worst economic downturn ever. At the same time, Powell and the FCC are plunging full speed ahead into a political struggle over the ever-thorny issue of media consolidation. Politics, the economy and the media are all converging, and Powell is the man in the middle.

As the newly appointed FCC chairman, charged with regulating the nation’s entire telecommunications industry (radio, television, telephone, wireless and satellite), Powell has reached unusual heights for a man not yet 40 years old. (“What is he, 38? God, that’s depressing,” sighs one envious broadcast lobbyist.) His swift ascent is all the more amazing considering Powell joined the public sector just five years ago.

After his exit from the Army in 1988, Powell attended Georgetown University’s law school. There he befriended William Coleman, a transportation secretary during the Ford administration. Coleman introduced Powell to Harry Edwards, the chief judge of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia, for whom he clerked. Powell then joined O’Melveny & Myers, Warren Christopher’s international law firm, for which Powell lobbied the government on behalf of Conoco Oil.

In December 1996 Powell joined the government payroll as chief of staff for Assistant Attorney General Joel Klein. Less than two months after Powell joined the DOJ, Sen. John McCain, R-Ariz., an old family friend, recommended Powell to fill a Republican vacancy and become one of the FCC’s five commissioners. (Actually, there was no vacancy per se; McCain, in an unusual move, simply urged that a sitting Republican commissioner not be reappointed for another term in order to make room for Powell.) In November 1997, Powell officially became a commissioner.

Less than four years later, President Bush appointed Powell to the position of FCC chairman, a move that fit in nicely with the administration’s early emphasis on appointing women and minorities to high positions.

To recap, here is the list of friends in high places who reached out in succession to help Powell over the last few years: former Transportation Secretary Coleman, Judge Edwards, former Secretary of State Christopher, Assistant Attorney General Klein, Sen. McCain and President Bush.

Now Powell is king of the Hill. “He has an extraordinary amount of bipartisan respect and goodwill on Capitol Hill,” says Scott Cleland, chief executive at the Precursor Group, a Washington financial research firm. “He has an extraordinary command of the material and he understands the issues. He starts with more political goodwill and political capital than any Washington leader.”

Says Hundt: “Powell’s job is as risk-free as any public service job could be right now.”

Borrowing a bit of Dick Cheney-speak, Cleland agrees: “Powell’s big-time popular in Washington.”

The question is: How long will his popularity last? Not everyone in Washington is enamored of Powell’s deregulatory tendencies. Powell’s response to Stearns’ query about media consolidation last spring particularly stuck in the craw of Sen. Fritz Hollings, D-S.C., the crusty party elder who first took a seat on the Senate Commerce Committee when Powell was just 4 years old and running around at his parents’ knees on one of the 20-odd Army bases he grew up on as a kid.

The surprising party switch this spring of Jim Jeffords, I-Vt., suddenly gave Hollings — the newly installed chairman of the Senate Commerce Committee — a forum to express his dismay at Powell’s comments. The senator called for a July hearing to specifically address media consolidation and the question of TV ownership caps and newspaper cross-ownership. (Without the caps, media giants like NBC, ABC, the Tribune Co., the New York Times and Viacom could cash in by drastically expanding their holdings, making it possible, for instance, for NBC to buy the Gannett newspaper chain if it wanted.)

Powell’s notion of “validate or eliminate” the ownership rules irked Hollings. “That, my friends, is not the law,” scowled the senator. “And that is why we are having this hearing today — to set the record straight.” Hollings pointed out that according to the Telecommunications Act of 1996, the burden of proof was on those who wanted to relax the existing ownership rules, not, as Powell suggested, the other way around.

That philosophical difference is at the heart of the consolidation debate. Deregulators such as Powell insist that the ownership caps unfairly confine businesses, and that unless the limits can be justified they ought to be abolished. Cap proponents like Hollings, a fierce defender of competition through media diversity who enjoys striking a populist stance against the “insatiable” demands of the media industry, insist that government plays a key role in protecting the public trust and that deregulation is not a cure-all.

Hollings also corrected Powell’s factual error from his earlier testimony that the TV ownership caps were lifted from 25 percent to 35 percent in the 1970s, noting that they were actually put in place in 1996.

Just barely, though. For all the inevitability that appears to surround the prospect of relaxing the caps beyond 35 percent today, just five years ago Congress had second thoughts about even going beyond the old 25 percent limitation. During a Senate vote on the Telecom Act in 1995, Sen. Byron Dorgan, D-N.D., offered an amendment to keep the TV caps at 25. To the surprise of nearly everyone present, it passed by three votes. One Republican senator then changed his mind, thereby allowing for a revote that night. During dinner, “several senators had some sort of epiphany,” according to Dorgan. The amendment was then narrowly defeated and the TV caps were raised to 35 percent.

Concerned that TV will follow the runaway consolidation that radio underwent when the Telecom Act eliminated virtually all meaningful ownership restrictions, Hollings topped off the hearing by introducing legislation that would handcuff the FCC. His bill would require the commission to report to Congress any attempts to loosen media ownership rules; the rules would go into effect only after Congress had 18 months to review them. Hollings has strong support from smaller TV broadcast companies that fear being swallowed up by the giants if caps are lifted.

It was a classic shot across the bow. Or in D.C.-speak, a push-back. Hollings had put Powell on notice; not only was his honeymoon in jeopardy, but if the well-liked chairman thought ushering in more media consolidation on behalf of big business was going to be a cinch, he had better think again.

“I think what has been revealed is an inconsistency in the chairman’s philosophy,” says Gene Kimmelman, co-director of the Consumers Union.

“He claims he’s just following Congress’ initiative,” says Kimmelman, who testified at the Senate hearing against any further media consolidation. “But the senator pointed out that chairman Powell quite obviously has a strong predisposition towards deregulation and has shown a certain disregard for legislative directives from Congress. Perhaps he needs to go back to the drawing board and clarify his approach.” (Powell was not available to be interviewed for this article.)

Just a few days after the Senate hearing, Powell did just that — he made his priorities perfectly clear. Voting along party lines, commissioners granted a waiver allowing Rupert Murdoch’s News Corp. to purchase 10 Chris-Craft Industries television stations for $4.4 billion — making Murdoch’s Fox television group the most powerful in the nation. The waiver was needed because the purchase violated three separate ownership and cross-ownership laws. (Conspiracy theorists will note it was Fox News, with the help of a Bush cousin in the control room, that first called the disputed election for the Republican candidate during the early hours of Nov. 8. If Al Gore had won the election, Powell would not be the FCC chairman today.)

Whether he likes it or not, the issue of media consolidation, and the accompanying political fireworks, will likely define Powell’s first term as chairman.

“It’s the most partisan issue the FCC faces,” says Cleland, “and it’s the one that will most challenge the chairmanship’s acumen.”

Indeed, Powell had hoped the commission would start the review process on newspaper cross-ownership in May by taking the first step of posting what the FCC calls a notice of proposed rule making. (A proposed rule is made, comments are filed by all interested parties and then the commissioners vote; the process can drag on for more than a year.) But the FCC commissioners couldn’t even agree on the wording for the rule making and the initiative was scrapped temporarily. Democratic commissioner Gloria Tristani, said by FCC sources to be eyeing an upcoming run against Republican Sen. Pete Domenici back in her home state of New Mexico, was adamant about not approving any proposal that even considered eliminating the ban on newspaper cross-ownership. But with three new commissioners now on board, Powell should have the votes to finally get the process moving.

Even as the issue of consolidation receives ever higher levels of scrutiny, Powell is also discovering that his attention is needed elsewhere. The economic collapse of the telecommunications sector is a bust that makes current dot-com woes pale in comparison, and it is happening on Powell’s watch.

Local, long-distance and wireless telecom companies and network-equipment makers have already cut 225,000 jobs this year, according to the Wall Street Journal, and “wiped out almost $2 trillion in stock market wealth,” making it nearly impossible for an economic recovery to take hold. Big losers have included Corning, Lucent, Nortel Networks and JDS Uniphase. The latter, once a tech stock favorite, announced in late July the largest write-down in business history: $45 billion. In just over one year the stock value of JDS, a leading manufacturer of components for telecommunications networks, has dropped from $153 to $9.

As the chairman of an agency that oversees the telecom sector, is Powell the unwitting captain of an economic collapse?

“The communications sector is his principal responsibility and it’s suffering the deepest recession of its history; there’s tremendous gloom,” notes Hundt, who suggests Powell has not provided enough leadership to help lure investors back to the telecom table. “The situation here is Powell could end up looking like Herbert Hoover — the best person for the job but who’s hit with a downturn he’s not personally responsible for, and then doesn’t react in a useful way.”

James Glen, an economist for Economy.com, disagrees. “I think the FCC chairman’s role is to ensure competition. You can’t blame [the bust] on regulators.”

But even free-market advocates, who believe that even more deregulation is the necessary cure for economic ails, are sounding worried. To Cleland, Powell’s responsibility is simple: “He said he’d be a deregulator. If he’s not and the telecom sector languishes, then he should be concerned.”

But is Powell simply a dedicated deregulator, or will his tenure at the FCC offer some surprises? Was the Chris-Craft waiver for News Corp. a sign of things to come, or simply a special deal for Murdoch?

Powell has given the public some mixed signals. When he first joined the FCC, Powell agreed that the rampant media consolidation uncorked by the 1996 Telecom Act was “scary.”

“The reason the pace is scary is because it’s hard to keep up with and to know when to put the brakes on,” said Powell.

“We could do a lot worse than Michael Powell during a Bush administration,” says one broadcast lobbyist opposed to further consolidation. “Perhaps with a sense of confidence and strength that he’ll go on to bigger and better things in life, compared to most telecom lawyers, Michael Powell may have the potential to be like a Supreme Court justice. People think he’ll vote one way and he turns out to be another Earl Warren.”

Powell has already shown the ability to throw a curveball. In June his FCC levied a $7,000 indecency fine against a Colorado Springs, Colo., radio station for playing a clean, or edited, version of Eminem’s hit song “The Real Slim Shady.”

The penalty came as a shock because for years the FCC had all but ignored listener complaints about radio’s increasingly raunchy programming. Also, during his inaugural press conference as chairman, when asked about broadcast indecency, Powell quipped, “I don’t think my government is my nanny. I still have never understood why something as simple as turning it off is not part of the answer.”

Powell also stressed concern about trampling over rights in order to regulate indecent content, telling the Washington Post, “It’s better to tolerate the abuses on the margins than to invite the government to interfere with the cherished First Amendment.”

Broadcasters, not to mention First Amendment activists who had viewed Powell as a hands-off pal, were incensed by the “Slim Shady” fine. “It was a little bizarre to go after Eminem, since everybody in the world is playing that record,” says Mary-Catherine Sneed, chief operating officer of Radio One, the country’s largest minority-owned radio station group. “It seems there are bigger fish to fry.”

Days after the fine, hip-hop impresario Russell Simmons buttonholed Powell at an awards gala and pressed him about the Eminem fine. “He told me he was committed to the First Amendment and it was not an attack on rap,” reports Simmons, who invited Powell to attend an upcoming Hip-Hop Summit in New York. Powell initially accepted, only to decline days later, citing “scheduling conflicts.” (As a rule, it’s best for rising Republican stars to avoid sharing a podium with Nation of Islam leader Louis Farrakhan, who gave the summit’s keynote speech.)

So what explains the left-field fine over Eminem? It was either politics or process.

Like his father, Powell takes pride in his moderate roots, although he also stresses that he’s “happy to call myself a Republican.” But according to a former FCC insider, early this year FCC commissioners received letters from a group of Republican senators urging the commission to clamp down on indecency over the airwaves.

“What was important,” says the senior source, “was it gave public cover for the commission to be more proactive in what it was doing. It emboldened Powell to be a more conservative Republican.” And to bring himself more in line with Bush’s culturally conservative administration.

The other explanation is process. Following a 1994 settlement with Evergreen Media over indecency fines levied against one of its stations, the FCC agreed to issue, within 90 days, new enforcement guidelines to help broadcasters better identify material that is potentially indecent.

For seven years the new guidelines were nowhere to be found as two Democratic-appointed chairmen, reportedly concerned about infringing on First Amendment rights, balked at issuing any new set of content rules. Within months of taking over the commission, Powell had the new guidelines distributed. The rules emphasized paying attention to overall context, and not just dirty words, so just bleeping out a few expletives would not protect a station against charges of indecency.

“Michael Powell is a stickler for process; it’s from his military background,” says Bill McConnell, who covers the FCC for Broadcasting & Cable magazine. “And he feels once he gets the guidelines out he has to enforce them.” Thus the Eminem fine.

Interestingly though, “Powell insists he was blindsided by this Eminem fine,” says McConnell. “The commissioners didn’t vote on it, because it came out of the FCC’s Enforcement Bureau. But he should have known about it.”

A hands-on chairman with instincts as keen as Michael Powell’s is not going to be blindsided by very many potentially headline-making initiatives promulgated by his own agency. But if such an embarrassment had to happen, it’s probably best that the issue at hand was a fairly minor affair. Because in coming months, as the political storm gathers around media consolidation, and the telecom sector gasps for its economic life, the stakes for Powell will get much higher.