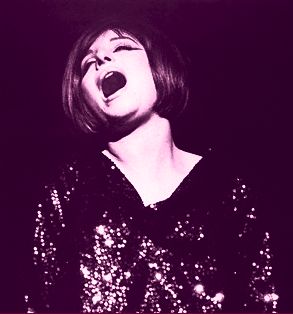

When we say that someone has the right look for a period picture, we usually mean that there’s something about him or her that captures the essence of a long-lost time: Lillian Gish, say, as a Revolutionary War innocent in “Orphans of the Storm,” or Liza Minnelli in “Cabaret.” But Barbra Streisand was the perfect choice to play the Florenz Ziegfeld-era comedienne Fanny Brice in “Funny Girl” for another reason: She has an art deco face.

It’s a face of Cubist beauty, a landscape of shapes and planes combined in a way that shouldn’t add up, and yet somehow make the best kind of visual sense. Even her eyes, outlined in the kohl-thick eyeliner style of 1968, speak of an era even further back: They’re the eyes of a Nile princess, a brainy pinup girl from Tutankhamen’s tomb, that ancient monument disturbed and opened in 1922, sparking a rage for all things Egyptian. In 1968 Streisand was the face of a new era and an old one: She was a modern beauty whose bold features could reinvent the past before our eyes.

She was gorgeous, she could sing and, perhaps rarest of all, she was funny. Streisand is probably the main reason William Wyler’s 1968 “Funny Girl,” beautifully made in its own right and now just beginning to make its way to theaters around the country in a crisply restored version, is so well-loved. Not everyone responded to Streisand. There are many who have always found her too abrasive. But the people who fell hard for her in “Funny Girl” — either the movie, or the earlier Broadway play that made her a star — are legion. Gay men, straight men, Jewish mothers and their daughters, gentile mothers and their daughters: People felt protective of her (“Poor little meskite from Brooklyn!” Mike Myers’ Linda Richman and Madonna cooed over her on “Saturday Night Live” a few seasons back), they were dazzled by her and they simply loved to watch her.

As Pauline Kael said in her review of the movie: “It has been commonly said that the musical ‘Funny Girl’ was a comfort to people because it carried the message that you do not need to be pretty to succeed. That is nonsense; the ‘message’ of Barbra Streisand in ‘Funny Girl’ is that talent is beauty.”

“Funny Girl” is a rags-to-riches story that’s almost comfortingly traditional, but its very conventionality serves as a blank canvas for Streisand to work on. Her Fanny Brice starts out as a funny, schoolgirlish mouse who gets a gig on a chorus line as unintentional comic relief — she’s great at funny awkwardness, but she’s not a straightforward dish, like the other girls.

Her early scenes, particularly one in which she wows an audience as a roller-skating chorus girl who, naturally, can’t skate, are a marvel of physical comedy, the natural counterpart to her wickedly on-the-money verbal timing. On those skates, she’s like a balletic ostrich on wheels, albeit one embellished with extra feathers and finery; she’s almost graceful in a knock-kneed, pigeon-toed kind of way. There’s nothing sexual about the way she moves, or the way she grins for the audience after a particularly dorky pratfall. Yet her sexuality is woven firmly but discreetly into the routine: You just know she’s the type of girl who laughs in bed when limbs get clumsily tangled or air escapes indiscreetly. Fanny can’t be bothered with embarrassment: Self-mockery is so much more fun.

No one in Fanny’s boisterous, extended, Lower East Side family (especially her mother, played by Kay Medford, the model of world-weary motherly vitality) thinks she’ll ever amount to much. Not that they lack faith in her talent — they just don’t want her to be disappointed if she fails. Of course, she proves them wrong, earning a spot in Florenz Ziegfeld’s show, where she stuns the legendary impresario (here played by a prematurely stuffed Walter Pidgeon, who’s nonetheless curiously amusing in the role) by singing one of her numbers as a pregnant bride. Ziegfeld is shocked and appalled, but the audience loves it, and it’s the beginning of Fanny’s blazing success.

She has personal heartache, too, of course: She falls for a ne’er-do-well aristocratic gambler type, Nick Arnstein (Omar Sharif), and loves him with such unwavering devotion that she can barely see his faults. Sharif, fine and waxen, has often been criticized as a dopey match for Streisand’s off-the-planet Fanny, but he’s really the perfect foil for her. He provides the movie’s essential visual and psychic acoustics: He’s a plain but not displeasing surface for Streisand’s brilliance to bounce against. Her bold beauty, so challenging in its directness, shows up the sleepy blandness of his merely handsome features. (Apparently, advance press photos of an on-screen kiss between the Egyptian-born Sharif and Streisand drew rumblings of displeasure from an Egyptian magazine. “You think Cairo was upset?” Streisand wisecracked at the time. “You should’ve seen the letter I got from my Aunt Rose!”)

In “Funny Girl,” Streisand works from the heart and the diaphragm — for her, the two are indistinguishable. The show’s songs, by Jule Styne and Bob Merrill, are big enough to stand up to her, but barely. Much of her singing — particularly in the famous “Don’t Rain on My Parade” sequence, beloved by drag queens and would-be princesses of all persuasions everywhere — sounds like a statement of arrival. There’s joy and triumph in it, and the requisite amount of ego, yet it doesn’t feel boastful or bloatedly hollow. Maybe that’s partly because her voice isn’t just big; it’s vast, with corners and hollows and shady corridors that give it a kind of spicy delicacy, even at its most assertive.

Although not all great singers make great actors, it sometimes happens that people who know how to interpret songs also have a knack for drama, knowing how to layer strata of emotional complexity even when they’re not singing. Streisand is that kind of actor: Her singing and her acting seem to spring from the same place, although there’s nothing monotonous or predictable about either of them. When she gazes into Sharif’s eyes, or when she does something that makes him laugh, there’s a look that passes fleetingly across her face, a mix of anxiety, vague insecurity but most of all, joyousness in the possibility that any man could see her as beautiful. It’s a cross between confidence and vulnerability that’s hard for an actress to pull off, but Streisand hits the note perfectly.

And her greatest moment of acting, I think, is also the picture’s strongest musical number. She begins her rendition of the standard “My Man” — it’s the song she sings after she’s said goodbye to Sharif — sounding rushed and uncertain, as if she just might take it into the same territory Billie Holiday took it, riffing on the same mood of resignation mingled with self-denigration. But as she moves through the song, Streisand — guided less by the intrinsic meaning of the words than by something deep inside her — steers it in a completely different direction. Instead of a tender, tearful affirmation of love for a man who’s just no good, she makes the song into a powerhouse of self-determination — as if it were possible to love somebody into good behavior. It isn’t, of course. But in the space of the song, line by line, Streisand punctures every potential doubt, as if she were popping a series of overblown balloons. By the end, there’s nothing to do but believe she can work the impossible just by the sheer nerve of her voice.

– – – – – – – – – – – –

You may have noticed that I haven’t yet said anything about the Nose.

Though I, personally, have not been blessed with one, I have always loved big noses, on men and on women. On men, they spell the promise of great sex — and if that sounds vaguely irrational, well, it is; on women, they seem both queenly and a little funny, a combination I always think of as terrific. My preference isn’t purely aesthetic: I also associate larger-than-average noses with the best qualities of all the Jewish people I’ve loved most in my life. I’m not trying to reinforce Semitic stereotypes here. It’s just that when you’re with someone who’s making you laugh, or who’s opening you up to something you’ve never thought about before, part of your joy comes from taking in the whole of the face before you, and the nose is right at the center.

If I had the power to decree what people could and couldn’t do with their noses, I would frown on rhinoplasty in all but the most extreme cases. Why would anyone want to leave her character on the cutting-room floor? If the gods give you such a gift, heaven forbid you should go messing with it. And I would point to Streisand, whose magnificent nose remains untouched to this day, as an example of a woman who knows the worth of a good schnoz. Streisand’s nose is a presence by itself, a feature that lends her face both gravitas and good humor; it’s an all-or-nothing nose, an ode to grandness, a reminder that the best things in life are never done in half-measures.