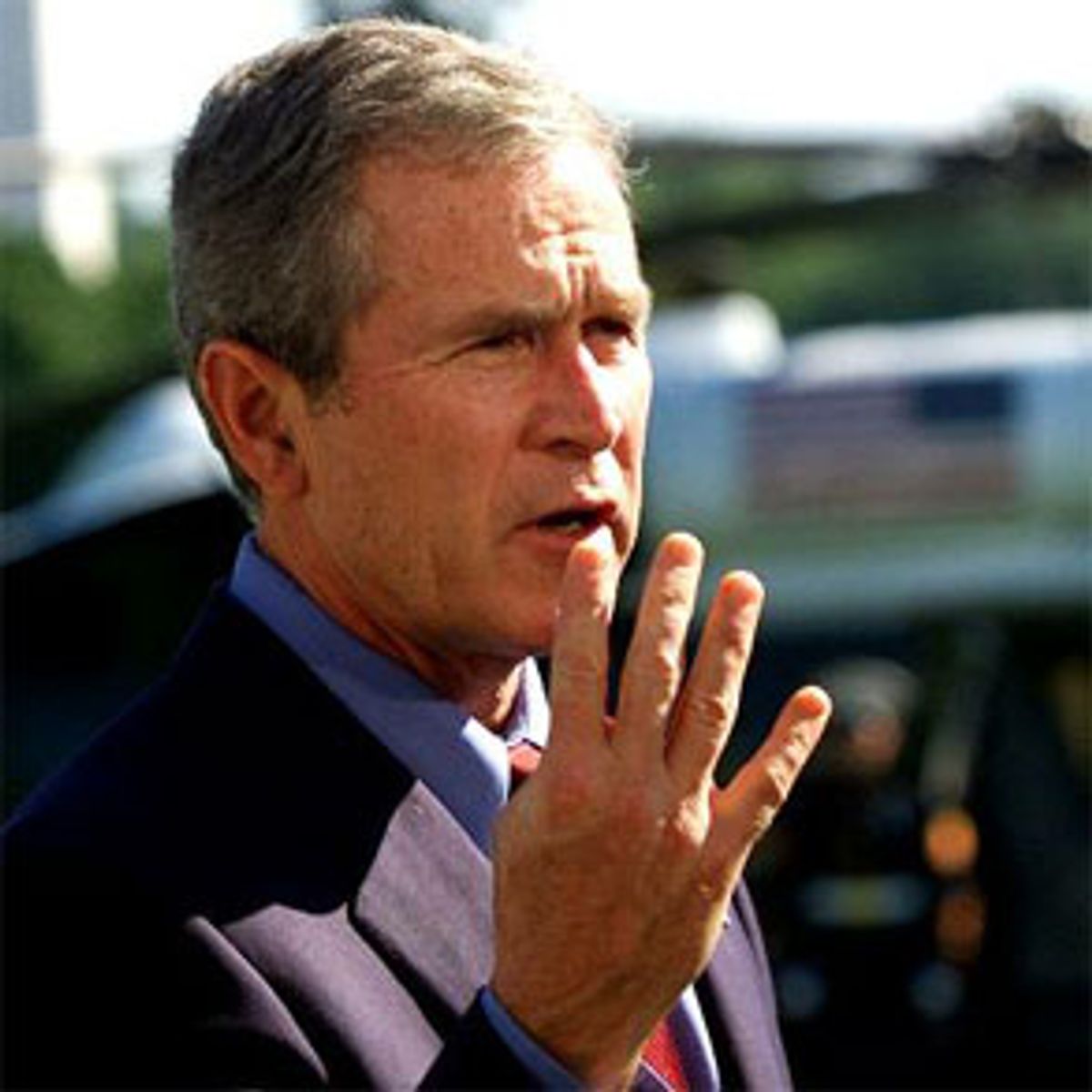

I want to say something that may not be congenial to every reader of Salon. But it's something that, I think, needs to be said after the last week or so. I am relieved that George W. Bush is president of the United States. I am more than ever proud of endorsing him last fall. Far from flunking the test of presidential leadership, as columnist Mary McGrory opined the day after the catastrophe, Bush has risen to this occasion with a variety of qualities that are distinct to him and not to everyone's taste, but qualities that I believe can greatly help us win this terrible war launched by evil men for evil reasons.

First, the caveats. It's clear by now that Bush's style is to put the executive into the executive branch. He tends to manage, not explain. He clearly feels that his first responsibility is to get the job done -- even if it means he is out of the public eye too much, or not insistent enough on explaining the reasons for his actions. When faced with a massive propaganda campaign, as the media directed after the inevitable withdrawal from the unworkable Kyoto Protocol, he has often failed to fight back coherently or eloquently enough. Sept. 11 showed the disadvantage of this impulse. Bush was placed in a uniquely confusing and destabilizing situation. Coded warnings were delivered to Air Force One that the president's plane and the White House were targets. We have no evidence to undermine this statement, and much evidence to believe it's true.

The security agencies decided to scramble the president's itinerary to foil any attacks. Maybe Bush should have returned directly to Washington. But at the time, it seems to me that the most important priority was to ensure that the president was in a secure place to direct whatever needed to be done. Instead of carping that he was not in Washington immediately, we should perhaps credit him with taking a political hit in order to fulfill his ultimate responsibilities as president. Congressman Martin Meehan opined that this explanation was "spin." On the contrary, it was the opposite of spin. It was a politically damaging act of civic responsibility. It says something of our priorities that we damn a president for this, rather than praise him.

Bush was back in Washington by evening to make his first, critical speech. It was barely adequate. It was designed merely to show that he was back, and that a war was underway. But from the beginning, Bush understood exactly what had happened and in his terse way, communicated the essentials. This was a war; and it was not only a war against terrorists but the regimes who harbor and protect them. On the day of the attack, he quietly framed the conflict. His subsequent statements and actions seem to me to be a paragon of what presidential leadership is about. He didn't lash out with a self-defeating and politically expedient strike, as other less resolute presidents have done. He gathered his experienced aides and directed a diplomatic, military and domestic strategy that already shows some signs of success. Frankly, we cannot know yet whether this war will be won quickly or how it will be handled. There will be time yet for such analysis. But Bush has started a process calmly, effectively and professionally.

And his emotions have been perfectly in tune with the mass of the country. Some have criticized him for tearing up in the Oval Office while recalling the tragedy. Personally, I found it deeply moving. It was real emotion -- not fake. It undergirded his resolve to fight back. In this, he is the antithesis of Clinton -- a man who used emotion for effect and idled while our national security weakened. And unlike Clinton, Bush didn't organize his schedule for photo-op political purposes. He went to New York not right away, when the media would have lapped it up. He let Rudy Giuliani perform miracles alone in a limelight that was more than rightly his. Bush doesn't need to elbow in on others' responsibilities or achievements.

And when he did visit New York, and hugged and chatted and bonded with the heroes of the recovery effort, he showed a side that New Yorkers have been so far reluctant to embrace. Even the New York Times melted at the sight of this young president clambering through the rubble to wave Old Glory. And when Bush ad libbed into a megaphone, he paid an immediate tribute to the men to whom we all owe an enormous debt. In the words of the New York Times, "Climbing atop a charred fire truck, draping his arm around a 69-year-old retired firefighter, Mr. Bush grabbed a bullhorn. 'We can't hear you!' someone yelled. 'I can hear you,' the president bellowed back. 'The rest of the world hears you, and the people who knocked these buildings down will hear all of us soon.'" So much for his vaunted inarticulateness in unscripted moments. This was a dignified president, able and willing to mingle and bond and mourn with the ordinary heroes of working class America, and also to connect their sacrifices and heroism to the struggle ahead. I'm sorry, but I didn't find these scenes fake or phony.

And while he rightly gave grave warnings about the conflict to come, Bush also took time to make a symbolic visit to Washington's Islamic Center, removing his shoes and standing shoulder to shoulder with America's peaceful followers of Islam. His words were eloquent; the tone pitch-perfect; the message exactly right. I have yet to read a word of praise from liberals for this occasion, or any comment on Bush's widespread support among Arab-Americans. Yet this now strikes me as an essential foundation for the just war we must now engage.

People still joke about Bush's lack of intelligence. But they make the usual mistake of conflating theoretical intelligence and practical wisdom. Wars require thinkers and strategists and complex minds. But above all they require an ability to focus, to stay on course, to make quick and difficult decisions, and to manage a complex political-military bureaucracy well. In all these respects, we have the right man in the job. He has assembled one of the most experienced national security teams in memory; he knows how to delegate; and he seems to have a composure and peace of mind that are critical in a war leader. Again, Truman comes to mind. You don't need a Ph.D. to win a war. You need a clear understanding of what war it is, how to win, and how to bring a country with you. I have nothing against Al Gore as a patriot and politician. But he cannot communicate or bond with ordinary people -- a terrible flaw in a war leader. Similarly, John McCain would speak wonderfully and lead courageously. But would he have the prudence and restraint to make the right decisions all the time? I trust Bush more on that one.

Lastly, his words. The story line that Bush is the dumbest, least articulate president in living memory is too good to alter. But it's simply not true. Take his recent press conference. Here's his stream of consciousness:

I believe -- I know that an act of war was declared against America. But this will be a different type of war than we're used to. This is -- in the past there have been, you know, beaches to storm and islands to conquer ...But I know that this is a different type of enemy than we're used to. It's an enemy that is -- likes to hide and burrow in. And their network is extensive. They have no -- there's no rules. It's barbaric behavior. They slit throats of women on airplanes in order to achieve an objective that is beyond comprehension. And they like to hit, and then they like to hide out. But we're going to smoke them out. And we're adjusting our thinking to the new type of enemy. These are terrorists that have no borders.

And by the way, it's important for the world to understand that we know in America that more than just Americans suffered loss of life in the World Trade Center. People from all kinds of nationalities lost lives. That's why the world is rallying to our call to defeat terrorism. Many world leaders understand that that could have easily -- that the attack could have easily happened on their land. And they also understand that this enemy knows no border.

This is a very thorough and persuasive account of where we are and what we have to do. It involves the world as it should. It doesn't flinch from the right descriptions of the evil men we now face. It is in a language any American can readily understand. It's not Churchill or Reagan, but it's not far off Truman, another plain-spoken man who was dismissed when he first came into office as inadequate for the job.

Then there are his formal words. The set speeches that Bush has so far given in his young presidency are among the most eloquent since Reagan. No, he didn't write them. But he picked the people who do, and they have performed superbly. Take these words from the National Cathedral: "It is said that adversity introduces us to ourselves. This is true of a nation, as well. In this trial, we have been reminded, and the world has seen, that our fellow Americans are generous and kind, resourceful and brave. We see our national character in rescuers working past exhaustion, in long lines of blood donors, in thousands of citizens who have asked to work and serve in any way possible ... As we've been assured: Neither death nor life, nor angels, nor principalities, nor powers, nor things present, nor things to come, nor height, nor depth can separate us from God's love. May he bless the souls of the departed, may he comfort our own, and may he always guide our country."

I suppose some will balk at the faith behind these words. But it was a prayer service and the words sprung from a faith that most Americans share. We are right to resist jingoism or blind support of a president in a national crisis. Dissent is necessary. But it shouldn't be knee-jerk. It shouldn't dismiss a man before he has barely begun to grapple with a war we all need to win. If there's one thing we know about Bush, it's his capacity to grow. Those of us who followed him in the beginnings of his campaign barely recognized the man by the final stretch. In office, he has grown further. In one short week, he went from adequacy to eloquence, from awkwardness and shock to an ease and fluency we had not yet seen. If the past is any guide, the man could grow much further in this conflict, and the world will be much safer and freer for it.

There will be time for criticism of the way the war is waged, its timing and efficacy and impact. But for now, when so much is uncertain, is it too much to ask that those who have long disliked the man or opposed his policies take a moment to give him a chance? Bush is a new president. He will make mistakes. He is far from perfect or flawless. Remember Clinton at this juncture? But if it is said, as Bush remarked, that adversity introduces us to ourselves, perhaps we should use this awful adversity to reintroduce ourselves to our president. We may even be pleasantly surprised by what we find.

Shares