When James W. Ziglar, commissioner of the Immigration and Naturalization Service, discussed last Thursday in front of a U.S. House subcommittee his investigation into the 19 terrorists implicated in the Sept. 11 attacks, it was difficult to decide which of his revelations was more alarming -- that immigration officials had no record of six of the terrorists, or that the other 13 might have been admitted into this country legally, despite ties to al-Qaida.

In fact, a breakdown of the 19 alleged terrorists from Sept. 11 reveals the following:

There are some overlaps in those categories, but those problems cover 12 of the suspects.

Among the few things that are clear now is that the system meant to control who enters this country failed miserably.

And is still failing. Attorney General John Ashcroft said on NBC's "Meet the Press" Sunday that there were 190 individuals in the United States whom law enforcement officials want to speak to and have been unable to locate.

After the initial shock of such facts, the average American is likely to eventually stumble upon the realization that the nation's immigration laws have problems. According to a Zogby International poll, 76 percent of the public feels that the government has not been doing enough to control the border and screen those allowed into the country -- an opinion that cuts across ideological and racial lines.

On Tuesday, the Congressional Immigration Reform Caucus introduced a number of proposals to shore up the borders -- restoring political ideology as grounds for a denial of visas, for example, and maintaining a computer database to keep tabs on foreign students. The caucus -- which saw its ranks almost double from 16 members before Sept. 11 to 30 members today -- e-mailed around its proposals to the other members of the House since regular mail has been suspended following the Monday discovery of anthrax in a letter mailed to Senate Majority Leader Tom Daschle, D-S.D. Two of the caucus' measures were already in the House anti-terrorism bill that passed last Friday, one that would deny entrance into the country to anyone who supports or is affiliated with a terrorist organization, and another that would give access to Justice Department information about visa applicants to officials of the INS and the State Department.

Not that this is the first congressional attempt to make the country a bit more selective in its non-immigrant visitors.

A few lawmakers have tried to close some of the loopholes that allow non-immigrant visitors free and unfettered abuses of U.S. borders. Some of those problems, had they been fixed as proposed in the past, might have had an effect on the Sept. 11 terrorists. And, most alarmingly, all of the loopholes had revealed themselves in prior instances of terrorism -- and yet the government allowed the problems to remain.

Chambers of commerce, free-trade advocates and other business-minded organizations opposed, along with immigrant organizations, efforts that could help secure our borders. Universities, eager for foreign dollars and campus diversity, protested moves to put foreign students under scrutiny.

The result, according to critics, is a system that grants the benefit of the doubt to a foreigner trying to obtain a visa. At Friday's Senate hearing of the Judiciary Committee's Subcommittee on Technology, Terrorism and Government Information, Steven A. Camarota, director of research for the Center for Immigration Studies, said the State Department's consular corps "has neither the manpower, nor the tools to fulfill this heavy responsibility properly" to screen for and assess those affiliated with terrorist or terrorist-sympathizing groups before granting visas.

But there's an attitude problem as well, Camarota told the Senate subcommittee. "Consular Corps has also adopted a culture of service rather than skepticism, in which visa officers are expected to consider their customers to be the visa applicants" rather than American citizens whose safety they are protecting. He said "visa officers are judged by the number of interviews conducted each day and politeness to applicants rather than the thoroughness of screening applicants."

Camarota said the consular corps needs to be beefed up, given better technology to make it easier to identify those on watch lists operating under aliases, and also given more discretion. "The law makes it extremely difficult to turn down an applicant because of his 'beliefs, statements, or associations, if such beliefs, statements, or associations would be lawful within the United States,'" he testified. That means someone who sympathizes with terrorists or organizes demonstrations that call for the destruction of the United States but hasn't yet actually funded or committed a terrorist act can still be admitted into the country. That, he said, needs to change.

And a State Department official agrees. "We've asked Congress to amend the Immigration and Nationality Act to make it easier for us to deny visas to aliens who support terrorism," the official says, speaking on condition on anonymity.

Such an amendment seems laughably obvious now, of course. But there were warnings long before Sept. 11 that such a reassessment of our current laws would be needed. In 1990, Sheik Omar Abdel-Rahman was on a watch list of suspected terrorists, but he was admitted into the country anyway. Considered the mastermind of the 1993 World Trade Center bombing, Abdel-Rahman was later convicted of conspiring to blow up the Lincoln Tunnel and other New York City landmarks.

In February of this year, the U.S. Embassy in London granted a student visa to Habib Zacarias Moussaoui, despite the fact that Moussaoui, a French Algerian, was on a French watch list of suspected Islamic extremists. Many in law enforcement suspect Moussaoui of involvement with the Sept. 11 attacks. He was detained in August on immigration charges after telling instructors at a Minnesota flight school that he was interested in learning how to steer airplanes, but not how to take off or land. He is currently in FBI custody.

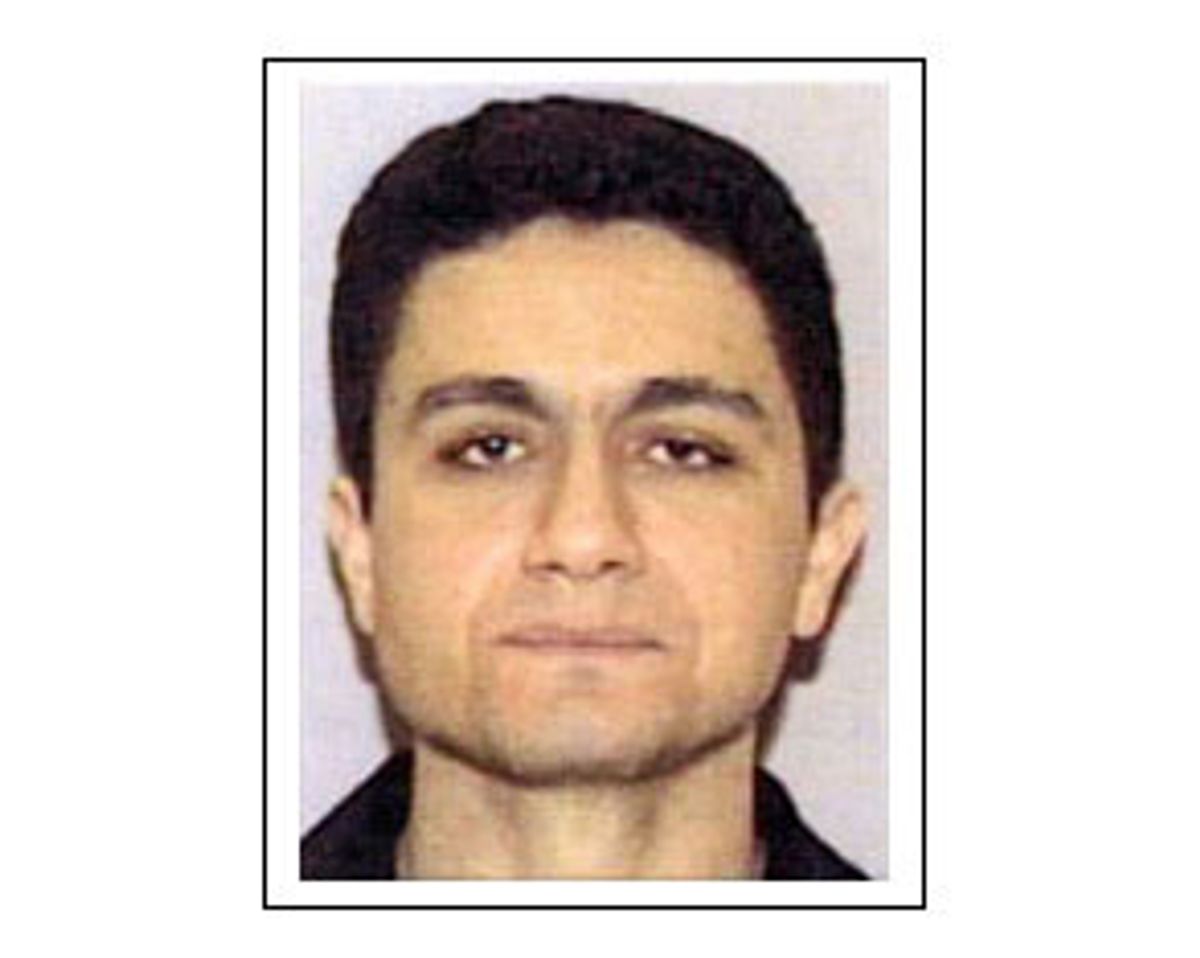

More recently, Mohamed Atta and Marwan Al-Shehhi were granted visas to visit the United States even though they had violated the terms of previous visas, according to the Los Angeles Times. According to the State Department official, prior immigration violations can prevent any further issuance of visas, though in this case that appears not to have happened. Atta was one of the hijackers of American Airlines Flight 11, from Boston to Los Angeles, which crashed into the north tower of the World Trade Center at 8:45 a.m. Al-Shehhi was one of the hijackers of United Flight 175, also from Boston to L.A., which hit the south tower at 9:05 a.m.

A simple criminal background check on visa applicants might also save American lives. Damir Igric, a 29-year-old Croatian, had been arrested in his native country on drug charges and illegal arms possession. Igric was granted a 29-day transit visa after arriving in Miami in 1999. He never left. On Oct. 3, he boarded a Greyhound bus from Chicago to Orlando. In Tennessee, wielding a box cutter, Igric slashed the throat of the driver. The ensuing accident killed seven people, including himself.

Then there are Khalid Almihdhar and Nawaf Alhazmi. In January 2000, Almihdhar was filmed by the CIA in the Malaysian capital of Kuala Lumpur meeting with an individual later implicated in the October 2000 bombing of the USS Cole. Alhazmi was a companion of his. Over the summer of 2001, the CIA told INS that Almihdhar and Alhazmi should be placed on the watch list and barred from admission into the U.S.

But by then both men had already been legally admitted into the country, Almihdhar in July 2001, Alhazmi in January 2000. Alhazmi's visa had since expired. But since there is no way to track visitors to this country once they're here, both men were free to travel unperturbed. On Sept. 11, they boarded American Airlines Flight 77, the Dulles-to-LAX flight that crashed into the Pentagon, killing 189 people. They bought their tickets using their real names.

Elaine Komis, a spokeswoman for the INS, says that the agency's information on arrivals is "pretty good" -- but that tracking individuals once they're in the U.S., or when they leave, is "not very good." Though there are 30 million admissions to the United States a year, she says, the INS has no idea how many exits there are, since airlines are put in charge of the matter and do a rather poor job.

As for tracking non-immigrants, the task is currently impossible. The INS complains of outdated computers and only 2,000 investigators, who focus on tracking down aliens who have already committed crimes (as opposed to ones who might be conspiring to do so), hunting smugglers of aliens, and finding illegal aliens in the workforce. Of the estimated 5 million illegal aliens in the country, 40 percent were admitted legally and remained after their visas expired, Komis says.

Sen. Kit Bond, R-Mo., recently introduced legislation that would call upon the attorney general to implement a tracking system for non-immigrant visitors wishing to enter the country, using the latest technology in biometrics, including retina and fingerprint scans, for tamper-proof visas. Those who overstay their visas -- as did three of the 19 hijackers -- would have their names spread throughout law enforcement offices. The State Department would be made privy to FBI information so as to conduct more thorough background checks on visa applicants.

This would presumably help the INS keep tabs on those individuals operating under aliases -- like the six as-yet unidentified Sept. 11 hijackers. Or Ayman al-Zawahiri, Osama bin Laden's chief deputy, who came to the country in the mid-1990s for a fundraising trip under a false name.

Bond's bill would also address the matter of student visas. While colleges and universities currently have to receive INS approval before accepting a foreign student, Conrad's bill would extend that requirement to other schools -- like flight academies.

A Senate Democratic source reports that Bond's bill will likely be added to the anti-terrorism legislative package during the House-Senate conference committee process.

In the immediate aftermath of the Sept. 11 attacks, Sen. Dianne Feinstein, D-Calif., chair of the Judiciary Committee's terrorism subcommittee, threatened the foreign student visa program with a six-month moratorium, but eventually backed off. Yet the system clearly needs reform -- and this fact is by no means new.

Rep. Lamar Smith, R-Texas, was first tipped off to potential abuses of the foreign student visa program during the prosecution of Eyad Ismoil, who came to the country to study at Wichita State in 1989. Ismoil dropped out of school but stayed in the country anyway, working at a store in Dallas. In 1993, he drove a truckload of explosives into the underground parking garage of the World Trade Center.

After learning of Ismoil, Smith worked hard to implement a major immigration reform bill, which passed in 1996. It included the Coordinated Interagency Partnership Regulating International Students, or CIPRIS, which would track the movements of foreigners living temporarily in the United States. If they didn't show up to class, the INS would be notified. But even after CIPRIS became law it experienced intense opposition from groups like the Chamber of Commerce and the Association of International Educators, which called CIPRIS "an unreasonable barrier to foreign students who seek legitimately to pursue their higher education in the United States."

In February 2000, a group of 21 senators headed by then-Senator and now Secretary of Energy Spencer Abraham urged that the implementation of CIPRIS be postponed. It was. Pressured by Abraham, then-INS Commissioner Doris Meissner agreed to delay implementing key provisions of CIPRIS until the senators' concerns could be worked out.

While CIPRIS floundered, Hani Hanjour was admitted into the country on Dec. 8, 2000. Having been accepted for study at the ELS Language Centers on the campus of Holy Names College in Oakland, Calif., Hanjour was granted a student visa. He never showed up for class. Hanjour is thought to have been at the controls of American Airlines Flight 77, which crashed into the Pentagon.

Funding and implementation of the CIPRIS program seems to now be going ahead. The Association of International Educators has apparently dropped its opposition. Ziglar has pledged a whole host of reforms, including developing a fully automated entry/exit data collection system at all ports of entry by the end of 2005. Technology will be improved, Ziglar promised the House subcommittee, and the management of the INS will be restructured. Ziglar, who has only been on the job for two months, praised INS employees and made it clear that commerce and the maintenance of the free market remain priorities in his agency.

"I don't know whether we would have possibly caught a couple of the terrorists that were involved in the attack on Sept. 11 or not," Smith recently told NBC. "But if we had perhaps apprehended one or two, we might have been able to unravel the conspiracy."

Shares