As I sat beside a merry child -- my own -- at "Harry Potter and the Sorcerer's Stone," sinking deeper into despond and boredom, I tried to fathom why the film was so empty, and so indifferent to the magic it kept blathering about.

What I saw was something I had always guessed, but something that has been buried in all the hysterical marketing success of Harry Potterism. Despite the scar on his head, Harry has no profound psychosexual life that drives him on a quest he cannot yet understand, but which amounts to an urging that could keep the ramshackle, episodic structure as cohesive, momentous and emotional as the unwinding themes in Wagner.

Now I can imagine the parents among you gasping in affront at the very suggestion that a Harry Potter film should be as loaded with sex (or psycho-sex, or mythic yearnings) as an episode from "Friends." For God's sake, you're saying, why rebuff something to which we may safely send our children, without fear of sexual staining, and premature damage. Good luck to AOL Time Warner if they're making hundreds of millions from an entertainment so wholesome, so unthreatening, so free from those dread things called knowledge or experience. And after all, wasn't your own child having a wonderful time there in the dark, no matter that you were sitting beside him, a seething, conspiratorial hulk of darkness trying to find dirty things? And so on.

To which I would reply, in brief, that literature, movies, myth and the possible enlightenment of our children one day are all far more important than two and a half hours in which weary parents may reckon that all is safe and secure.

I am not hugely impressed by J.K. Rowling's books, though they are immeasurably more interesting and potent than this wretched, craven film. And since, for this moment, few things loom larger in the imaginations of our children, this protest is worthy and important. We deserve better. Our children have to have something more compelling. The only true measure of greatness in Harry Potterism is not the final cash flow in the franchise, but whether young minds are formed, advanced and imperiled by its ideas. For growing up has to be dangerous. And if the greatest defense of any work is that it resists growing up, that it urges the extended stagnation of childhood, then we are in trouble. And it is a far greater danger than terrorism, because it is one we are nurturing ourselves.

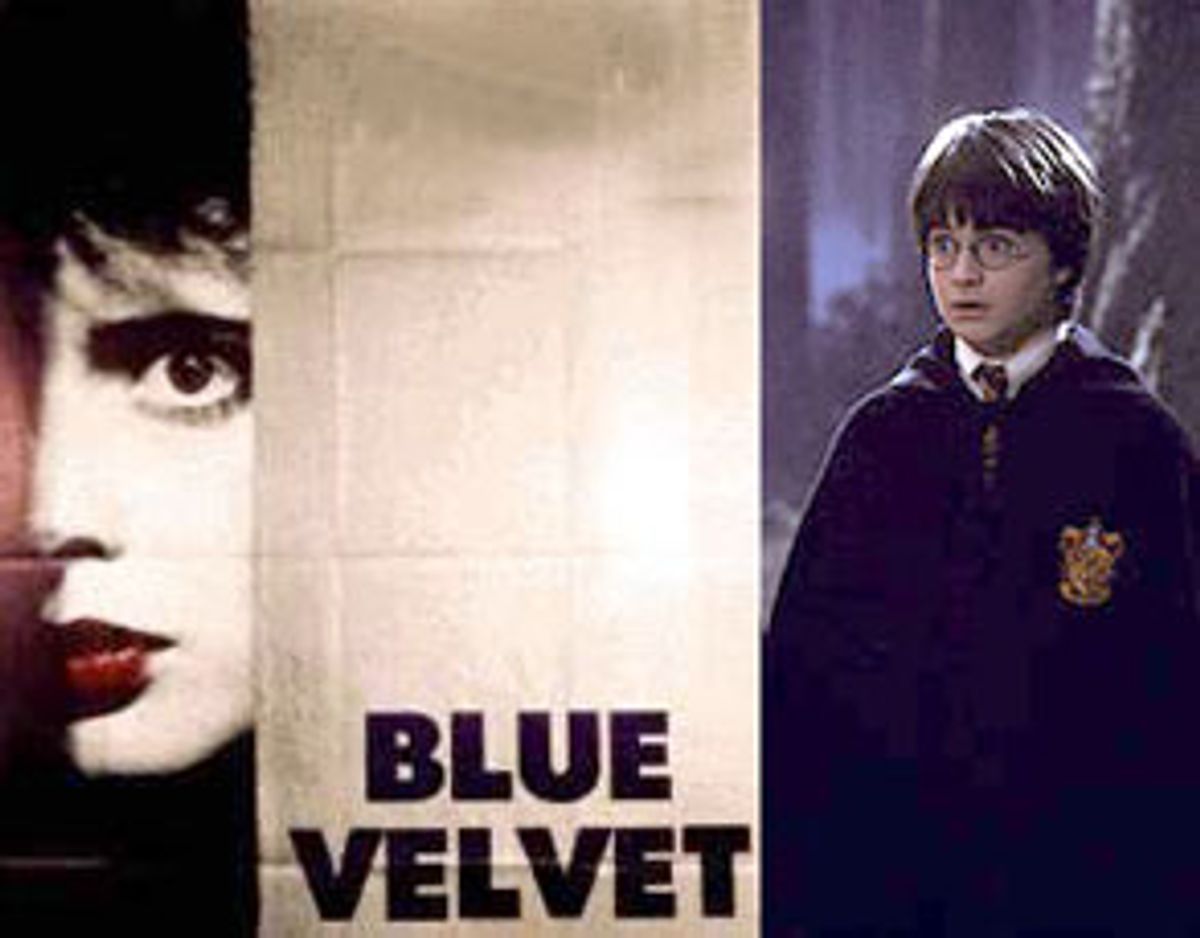

Now let me establish one thing: I'm inspired by recently having re-viewed David Lynch's "Blue Velvet" a few days after seeing the Harry Potter film. I am not asking that children, or anyone younger than 15 or so, should be allowed or expected to see "Blue Velvet," for it is a very disturbing film -- that's how great it is. (Indeed, I am angry that any child in America can see "Blue Velvet" -- or have to sit before it, trying to absorb its sensational, suggestive and very frightening events -- just because they are allegedly in the care of their imbecilic parents.)

Nevertheless, I want to say that all children's literature and all children's stories -- if they are great and enduring -- work off a metaphorical quest, or off the idea of a loss or an injury that needs to be redeemed, in which the gaining of dangerous knowledge can lead to maturity instead of deformity. That is where "Blue Velvet" is relevant, for it is a childish story, or a fairy tale -- if you want to use the phrase that we inherit from Perrault and the Brothers Grimm -- in which adults may follow the desperately dangerous (but normal) passage of infantile sexuality to the adult condition.

It is a story about a very nice, pretty, good boy, Jeffrey (Kyle MacLachlan), and how he negotiates his own voyeuristic urge and the storm of new knowledge that comes from it. And it's about whether he is destined to be with his sweet, good girlfriend (Laura Dern) or to be obsessed by the dark, fallen, sickly older woman (Isabella Rossellini).

Because it is meant for adults, the movie language of "Blue Velvet" is often overt -- we see flagrant, helpless, victimized nakedness; we hear the roaring language of incessant "Fuck!" from Frank Booth (Dennis Hopper); we shudder at Frank's confrontations with Jeffrey and the ecstatic charge "You're like me." To be blunt about it, we see how much good and bad magic, or spirit, or psychosexual energy there is raging inside us all. And "Blue Velvet" was so startling because it found a way to get that dreamy level of the child's experience. (Again, granted that it was unfit for any child.)

But children's literature has grasped the nature of symbol and metaphor for centuries. And it has known inoffensive ways to address that tremulous moment all children dread and desire -- the rite of growing up. I don't think there are actually examples of great children's literature without it.

This essay is not meant to be large enough to cover all of that, but let me take one example, the more intriguing in that it is now nearly 60 years old -- I mean "Bambi," which opened in the first year of America's experience of the Second World War. That may seem incidental, and surely Bambi was planned long before Pearl Harbor. But it was conceived and made after 1939, and I think it's legitimate to see that as the emotional background to its sense of peril.

"Bambi" is, in many ways, childlike: It is pretty; it is often sweet; it focuses on young animals coming into the world and finding their feet. "Bambi" is also astonishingly prepared to grasp very large fears. Bambi loses his beloved, tender mother -- she is shot by men in the meadows -- and thus passes into something like companionship with his aloof, austere father. One may shrink from the consequences of this passage in many ways. For it seems to say that young males need to be as hardened as their fathers and to put aside maternal feelings. It was a narrative turn of huge daring in 1942 to have the mother killed (I and many infants were in tears because of it -- or so I was told). And I think one has to see the thrust as being warlike -- or something likely to help virtuous males defeat both fire and wolves. But "Bambi" was made that way for 1942.

Whereas, it is quite plain that the first Harry Potter film wants to avoid being too frightening, too disturbing, too much engaged with nastiness (let alone evil), and too strong. For it is the law of the franchise that it would rather have Harry go on forever than grow up. This first film has already eclipsed the true wounding of Harry in being a foundling, in having lost parents, and in being so abused by the Dursleys. Why? Because I think AOL and so on were too anxious not to offend or arouse.

Harry does not need to be exposed to the dangers that face Jeffrey in "Blue Velvet." But he should feel his destiny; he ought to be more moved by some things than he is yet to understand. The film needs to believe in magic -- but its head and heart are locked into box office.

Shares