“You want to know the routine?”

Charles Christophe takes a deep breath, stifles his tears and recites the details of his new life. “We wake up. I bring her to day care. Then I go into the city to look for office space in midtown. By 6 I’m back. I buy the groceries. I pick up Gretchen from day care. I feed her. I give her a bath. I put her in bed. We read books until she falls asleep. I do the laundry. I go to sleep. The weekends are the same; we are together.

“I tried with a baby sitter, but she doesn’t feel comfortable,” he says, words away from a resumption of sobbing. “She cried, ‘Mommy, Mommy, Mommy.’ She’s barely learned to say ‘Mommy.'”

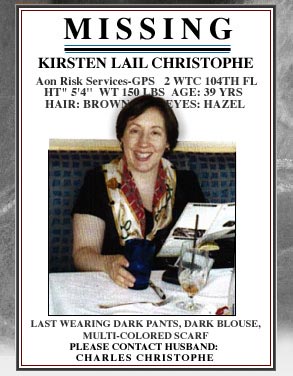

Gretchen’s first birthday was Sept. 13, two days after her mother was killed in the attacks on the World Trade Center. That night Christophe bathed his young daughter for the very first time, straining to listen for the phone as Gretchen splashed and screamed for her mother. He was certain it would ring at any moment, that Kirsten couldn’t get to a phone, that perhaps she was stuck on the train home.

“She always calls. She’s always good in a disaster. She always knows what to do,” says Christophe, who still refers to his wife in the present tense.

He went down to the basement to get some of Kirsten’s breast milk out of the freezer — she had saved a two-month supply, pumped at the nursing station on the 104th floor of Tower Two. She had called from her office that morning to say that the first tower had been hit by a plane, that she was OK. An hour earlier Christophe had kissed her goodbye in the lobby and rushed off to his office a block away on Broadway. He had been late for a court date.

Three weeks later, Kirsten Christophe’s body was identified with the help of DNA derived from a sample of Gretchen’s baby-fine hair. And Charles was forced to accept that suddenly, officially, unimaginably, he was a single father.

“This is my life now,” he stutters. “It breaks my heart.”

Many of us have navigated beyond our immediate and emotional reactions to the events of Sept. 11. We have crammed the horrifying images and attendant incomprehension into a mental closet that won’t quite lock behind us. The door still flies open from time to time, jimmied by the force of an unexpected visceral reminder.

But Charles Christophe lives behind that door, stranded there with hundreds and hundreds of other men. For them, the closet is sealed shut against their former lives. They used to be husbands and fathers, balancing the roles with the help of their wives, their children’s mothers. Now they are widowers and single fathers, their lives composed of constant and inconceivable challenges, both logistical and emotional.

Americans have endured the loss of male veterans of war in staggering numbers. But we have never experienced the loss of hundreds of women, many of them mothers, in a single day in what is now described as an act of war.

It is impossible at this stage to know how many wives died that September morning — even the total number of those killed is disputed by the hundreds every day. Originally it was estimated that more than 1,000 women died in the attacks. That number has slipped into the unknown hundreds, still a figure of historical significance. Out of the 36,568 Americans killed in the Korean War, only two were women. In Vietnam, just eight of the 58,204 who died were female. And in the Gulf War, when 383 Americans were killed, a total of 15 women were lost.

“When soldiers die, there’s usually a woman taking care of the family. It’s a different ballgame,” says Rabbi Earl Grollman, who has written more than 20 books on grief and mourning.

Many of the women who died on Sept. 11 worked at home as tirelessly as they did in their WTC offices. They did the laundry, cooked the meals, shopped for groceries, cleaned the house. They curated their families’ social lives and orchestrated their daily routines. Their families don’t experience their loss just through the disappearance of a familiar laugh, a tender touch or a quirky sense of humor. The emptiness created by their deaths stretches to fill each corner of the daily lives of the people they left behind.

For the women’s husbands, this means that, in addition to the overwhelming task of grieving, they confront daily demands and myriad tasks, many of which are completely unfamiliar. At the same time, they are in many cases the sole caretakers of young children struggling with inner suffering, as well as a need to return to their old routines.

“Everyone’s sense of safety has been shaken, and children more than ever need routine to have a sense that the adults will be there and be in charge,” says Ronnye Halpern, a widow who coordinates bereavement services at Cabrini Hospital in Manhattan. “Children haven’t formed inside themselves an internal kind of structure, and routines do that for them on the outside, which can be very reassuring. Baths, meals, whatever can be established — it’s going to be different than it was before, but you do find a new way of living. That’s the task for everybody.”

And it is an incredibly painful task for widowers, who are aware of the necessity of routines but are struggling mightily to establish some. “Dinner is the most difficult time of every day,” says Harold Weiss, who lost his wife, Margo, in the attacks. She had been in her office for only 10 minutes before the first plane hit her building. She was on the phone with a friend at the time, discussing 2-year-old Jason’s first day of school. “We still haven’t resolved how we have to do meals in the long term,” says Weiss. “At least in Manhattan there’s a lot of takeout available.”

But dinner is easy compared to some tasks that seem almost insurmountable. “We’re at the stage where my 9-year-old daughter is thinking of her body changing,” says Weiss through tears. “What do I do then? What will the rest of her life be like? Everything from brushing her hair in the morning,” he says, pausing to get his breath. “My God, I had never even brushed her hair.”

“In all of this, the grief is devastating, of course, but maybe it is the raising of daughters which is the most terrifying,” says Clark University professor Cynthia Enloe, who studies the experience of widows and war. “I never hear women who are suddenly widowed with young children talk about this kind of fear. They may be completely overwhelmed financially, but they don’t ever seem to be scared about how to be a parent,” she says. “It’s usually very different than this. They draw in the help of those around them. They’re not so alone.”

Christophe hasn’t consciously rejected help, but circumstances have made his new life unbearably solitary. He quit his job after the attacks to search for his wife and care for his daughter. He mentions a few friends who live near him in Maplewood, N.J., one of whom escaped Tower 1 and accompanied Christophe on his hunt for his missing wife in those frenzied first few weeks.

“He’s the one who has understood it the best, but there’s not so much time to see him now,” says Christophe. “I have to find an office, to get back to work and start paying the bills now, not just take care of Gretchen.” In addition, Christophe’s family is far away. His father, also a widower, lives in Europe. His wife’s family lives in the Midwest. Kirsten’s sister came for a couple of weeks after the attacks, then her mother took over, but she needed to return home soon after to care for her own husband, who was diagnosed with cancer this summer. She’ll return for the Christmas holiday, but will have to leave her son-in-law alone with Gretchen soon after. Thanksgiving was a couple of hours at a friend’s house, then home to bathe Gretchen and put her to sleep.

“When I was notified about the body I was by myself,” says Christophe. “You have to go to the cemetery, find a place for the grave. How do you know what to do alone?” His thoughts, as always, return to his wife. “We were so close, so happy. We talked all the time. Even on business trips, we’d be on the phone for hours. My cellphone bills! And now there’s no one.”

Christophe sought out a therapist in the first days, but since then has done his grieving alone, lost in the demanding schedule of his new role as a single parent. “I needed to talk to someone just a few times, because I was going to explode. So there was a kind of release of what was inside of me, but then I had to get on,” he says.

This is typical of how men tend to mourn, say those who counsel them, especially in the first six months or year of mourning. Women, in contrast, tend to be quicker to reach out for support, both among their friends and in more structured bereavement groups. “Women will talk and cry with other women, but men in general go back to work. Men will change the subject when asked about how they’re doing,” says Grollman. “In any support group, if men make up 10 percent of the people there, you’re lucky.”

“They’re still in shock, just trying to get through what they have to do each day,” says Halpern. Few people, women or men, she says, are seeking treatment. “Last year I had a wait list for my groups. Now, it’s like pulling teeth.” Bereavement groups set up around the city have reported a complete absence of new widowers — evidence of the gender divide in mourning.

“They won’t ask for directions — you think they’re asking for help?” asks Halpern. “Men are taught to act strong, to focus on moving beyond it. Defenses have always been given a bad rap, but they’re what help us survive.”

In fact, says Halpern, it’s hard to imagine how men like Christophe would manage the daily pressures of sudden single fatherhood without the aid of emotional shock to push them into their new tasks. “I guess you could call it a sort of blessing,” Halpern concedes. “Women need the process; men need to have their plan.”

Rabbi Grollman worries about how long these men will bottle up their shock and deal with it alone. “Grief is grief, and if men want to grieve in a different way than women do, they should be allowed to,” he says. But the longer they keep it to themselves, the harder it can be to manage. “It becomes a kind of emotional constipation,” he says.

Some people believe that the very public nature of the calamity and the first days of mourning that followed it may have made the process of recovery even more difficult. “Men tend to have a very difficult time with group shows of grief,” says Scott Campbell, coauthor of the 1996 book “Widower: When Men Are Left Alone.” “In this situation, I think it was very helpful at first to have the whole country, the whole world even, mourning with them. But a few weeks later people moved back to their lives, and they were left to deal with it all alone, in perhaps a more intense way, coming down from that initial feeling of support.”

For men who do enlist help, it tends to be an intensely private enterprise. Weiss has sought therapy for himself and for his daughter, but their counselor comes to their Manhattan apartment and speaks with each of them separately. He is fortunate to have resources to assist with the logistics — his mother moved into his Upper West Side apartment building to help out, and he has two baby sitters whom his children love. This extraordinary support has allowed him to spend more time engaging in his grief rather than in the multitude of daily parental pressures that burden fathers who are newly single and grieving.

“I think that my experience in this process is learning that men are a lot more emotional than you’d think, but it’s very private, and very raw,” he says.

Weiss, like Christophe, speaks of a devastating loneliness that has intensified with the holidays, even as he is surrounded by loved ones. “Having gone through a holiday weekend with loving family all around, I still felt so lonely, so strangely lonely that day,” Weiss says of a difficult Thanksgiving — a day his wife used to relish. “Because of the nature of what I was missing, of course. She’s just not replaceable.”

This painful fact is evident not just in Weiss’ heart, but everywhere in his life now. He has had to hire a wake-up call service, since Margo never forgot to set the alarm clock, but he always did. “Margo was the center of our family,” he says. “She took care of all of us, took care of everything. What’s so cruel is that she probably felt better about herself and was looking forward to the future more just before she died than any other time in her adult life. And she was beautiful. God, she was just so beautiful.”

After Thanksgiving, Weiss decided to begin the heartbreaking process of going through Margo’s closet with his daughter, Parker. He felt it was time to try to move on, but it was a process he quickly aborted. “I barely began,” he says. “Everything brings back a memory, memories of when she wore a particular dress, how stunning she looked. I was so lucky. And then there are other things I know she never wore. That’s really hard, too. I can’t really do it yet.

“To see it all, you’d think she’s still living here. I’m still expecting her to walk down the street,” continues Weiss, his voice trembling. “But obviously, I know intellectually that that’s not going to happen.” It will be up to 9-year-old Parker to select which of her mother’s outfits she would like to save. She has already chosen her mother’s wedding dress and shoes.

“I am really focused on my children and what is best for them. Everything else is secondary,” says Weiss. And it’s clear that while he is responsible for making major household decisions and delegating all he can, he wants Parker to decide how she’ll respond to her mother’s loss. Her first choice was to write a eulogy for her mother’s memorial service in September, which she courageously delivered herself.

“She was very poised and brave,” says Weiss. “It wasn’t morbid, just her words and thoughts about her mom, and how she’s extraordinarily impacted by this.” Parker also opted to change her Halloween costume. She was planning to go as a vampire in Victorian dress, but felt that day that her creepy garb hit gruesomely close to home. She went trick-or-treating instead dressed as a ’40s movie star. Her heroic date for the evening, appropriately, was a firefighter — 2-year-old Jason’s costume of choice.

Parker doesn’t want to talk about her mother’s death yet — and Weiss doesn’t push to her to do so, outside of her private therapy. She has thrown herself into a routine of gymnastics, piano lessons and chorus, feeling more comfortable outside the sad confines of the family’s apartment.

Weiss feels the same misery, which he fears will only intensify if the family stays home for the holidays. Weiss, although Jewish, has assembled a beautiful collection of ornaments over the years. Each winter he, Parker and Margo would decorate their tree together. This year, the box of ornaments will be left behind in New York when the family travels to California to spend two weeks with Margo’s family.

And in the new year, the Weiss family will make an even more difficult trip. They’ll go to Hawaii, where Margo was raised, so Jason and Parker can see for the first time where their mother spent a childhood very different from their newly tragic ones. “We planned this trip long before all this. And now we feel like we just have to go. You never really have a chance to say goodbye,” says Weiss.

In the three months he has been a single father, Weiss has learned what to pack to take care of toddler Jason and knows not to forget Parker’s hair-detangling spray. “I think she’s figured out by now that I’m never going to be very good with her hair,” he says. “I can never be her mother for her. And the only thing I can ask for from her, from myself, from everybody, is just an enormous amount of patience — just time and patience.”