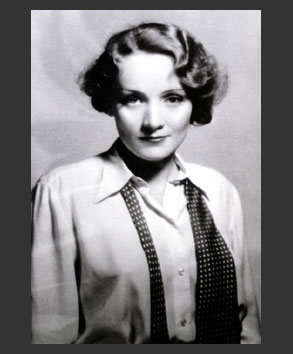

“Most women, according to an old joke, have gender but no sex. With Dietrich the opposite is very close to the truth. She has sex, but no particular gender … Dietrich’s masculinity appeals to women and her sexuality to men.” That’s what Kenneth Tynan wrote about Marlene Dietrich in 1957, and anyone who’s ever seen “Morocco” will immediately recognize it as the truth.

Dietrich’s entrance in that film is one of the most perverse and startling in the movies. A nightclub where the air has long ago been replaced by smoke, populated by placid revelers who breathe in all those “lovely injurious tars and resins” as if they were inhaling country air. Enter our chanteuse, Marlene, in tails and top hat (a look she was to don in her stage shows for years). Circulating among the contented damned who make up her audience, she approaches a woman, takes a flower from her and asks, “May I keep this?” Then, as a thank-you, bends over and kisses the woman right on the lips, lingering just enough so that there’s no chance of mistaking it for an innocent peck. But she’s not done yet. As the crowd goes wild, congratulating itself for its own sophistication, Marlene tosses the flower to the impossibly gorgeous young Gary Cooper as the French Legionnaire who’s been taking in the show.

It’s a scene calculated to drive everyone watching it wild, an impudent rebuke to the impoverished notion (reactionary as well as p.c.) that our sense of eroticism is defined by our own orientation.

There were others who were less wowed. Louise Brooks, another resident of Tynan’s pantheon of movie goddesses, who beat Dietrich out for the role of Lulu in “Pandora’s Box,” called Dietrich “that contraption!” and there’s a kernel of truth in her dismissal. Dietrich was never a “natural” presence, which isn’t to say she wasn’t a born movie star. But there was always a sense in which her heavy-lidded looks and that voice, husky in memory and yet always surprisingly light when you hear it again, had been worked up, manufactured.

She and Garbo were the exotic stars who orbited around each other in ’30s movies. But where Garbo had a somnambulant, ethereal presence, a sense in which she was communicating less to her leading men than using them as a vessel with which to speak to the gods, Dietrich was, for all her glamour, of the earth, ever so slightly vulgar, a broad who had transformed herself into a sophisticate without leaving her roots behind.

Garbo seemed naturally not of this earth, whereas Dietrich was tied to it, celebrated it. And yet, for all of Dietrich’s achieved artifice, she seems more real, or at least more tangible, more approachable. This isn’t a woman who requires you to watch your language, or ask permission to smoke, or pretend that sex is the farthest thing from your mind. The frank, almost lewd heaviness of her expression, the hint of cruelty and power so potent it doesn’t need to be exercised to devastate (“she can destroy any competing woman without even noticing her,” Hemingway wrote) tells you it’s certainly not the farthest thing from hers.

That approachability is part of what men have always loved about her. And it’s tempting to think of Dietrich, who loved men’s clothes even more off screen than on, as the movies’ George Sand. There was no protestation of sexual inequality in her garb, no haughtiness (the way there was in Katharine Hepburn’s wearing pants — that was the taunt of a well-brought-up girl flouting convention). If the tailored suits and men’s shoes she had copied to her own size were a provocation, it was an unconscious one. Jean Cocteau once rhapsodized, “When you wear feathers, and furs, and plumes, you wear them as the birds and animals wear them, as if they belong to your body.”

The same is true of her suits. Looking through the nearly fetishistic photos of Dietrich’s possessions that take up a good portion of the new book “Marlene Dietrich: Photographs and Memories,” you can’t see her Watson & Son evening suit, or her gray tweed travel suit (which she donned for train arrivals) without seeing her in them. The clothes don’t complete her, she completes them.

“Photographs and Memories” is full of traditional glamour shots — Dietrich in furs and gowns and jewels, lounging on chaises or leaning against walls, or just looking off into the distance, imperiously oblivious to the camera. Beautiful as they are, these are the “contraption” photos. They’re pregnant with an awareness of the come-on Dietrich is directing to the lens. The passivity of her head thrown back or eyes closed in sleepy, bored ecstasy isn’t at all natural (the way a 1935 close-up of her lounging poolside in her Hollywood home is).

She’s learned how to fake it, do what’s expected of a star. And do it like a pro, not at all like the awkward young German star you see in a photo taken with Charlie Chaplin on the set of “City Lights,” her legs carelessly crossed but her unease betrayed by the arms drawn tight across her chest. Dietrich’s posed formal photos are stunning and unsatisfying. Gussied up in movie star regalia, she looks less at home in her glamour than almost any of the stars you see from that period in the photos of George Hurrell or Clarence Bull. (The exception is a breathtaking shot of Dietrich taken during the filming of “The Garden of Allah.” Dressed in a clinging and diaphanous beige chiffon gown, she stands in the desert, the wind pressing the dress even more closely to her body, its sleeves spread out like the wake of a wraith. Her eyes closed, Dietrich looks ready to sacrifice herself to the elements, and also as if she might be the goddess controlling them.)

It’s the photos of Dietrich in drag that are the real turn-on in this book, the most sophisticated exuding such ease that you wonder if this woman ever sweated, ever put a wrinkle in any garment she had on. Sitting next to Douglas Fairbanks Jr. at a Hollywood screening, dressed in a man’s suit and tie, her hand reaching down as if to carelessly scratch her ankle, Dietrich looks completely at ease, as she does in another shot, dressed in a white suit and matching beret, laughing as she poses with Maurice Chevalier.

This is a woman who, for all her artifice, found her greatest allure in casualness. “Photographs and Memories” offers a moving section of pictures taken during World War II, when Dietrich, refusing Hitler’s imprecations to return to Germany, threw herself into the Allied cause, entertaining troops, traveling with them, even getting her wish to be with the American army as it entered Germany. She’s more beautiful in her khakis outside the tent designated as her dressing room than in the spangled gown she wore to do her shows. Digging a foxhole in fatigues, posing for a photograph taken by her lover, the great French star Jean Gabin (who had returned to France to fight with De Gaulle), driving in a jeep or hunkered down outside her tent in the GI uniform she eventually wore, Dietrich looks fulfilled, being a soldier in the only way open to her.

Two photos testify to the ardor she felt. In them she stands in a vast open field, as her beloved 82nd Airborne Division flies overhead, dropping parachuting soldiers. Her back is to the camera in both photos, but her body language is one of enthrallment, rapture. Essentially these are photos of lovemaking. Not sexual desire but, evident in the open arms and head tilted toward the sky, a sense of a spirit trying to escape its body to embrace the men drifting down in open parachutes as far as can be seen. At the end of “Morocco” Dietrich had doffed her high heels to follow her lover Gary Cooper into the desert. A dozen years later, that wildly romantic movie gesture would be transformed into one of real devotion, and these photos surpass, in sheer romance, any scene she ever played.

But back to the screen image. The key to Dietrich arises in “Photographs and Memories” out of the contrast between two photos, arrayed on facing pages. In the first Dietrich wears the wide curls and beauty mark of her role as Frenchy in “Destry Rides Again.” Her eyes are as heavy-lidded as always, the plucked eyebrows the trails of two shooting stars. The skin on her face and bare shoulder looks so creamy that you’re certain, if you could touch it, your fingers would melt right into the surface. It’s a luscious photo, and yet it doesn’t quite have the allure of its opposite. In that photo, Dietrich wears the same expression, except that the beauty mark is gone, her hair is pulled back, and a cigarette dangles from her lips. Oh, and the outfit is different. The boa of the first photo has been replaced by a white naval officer’s uniform, cocked braided hat, tie, jacket with epaulets. It’s a severe look, a knowing look, and Dietrich is completely at ease with its contradictions.

Just as Dietrich seems both man and woman, the thrill of that photograph is neither masochistic nor sadistic. It doesn’t make the beholder — whether gay or straight, man or woman — want to be dominated or dominate her. The thrill lies in the promise of a sexual equal, of meeting on a level ground where no desire is subordinated to either traditional roles or biology, where sexual hunger is matched by your partner’s. I don’t mean to make Dietrich sound like some seeress prophesying the end of gender. That would be to reduce eroticism and glamour to the crushingly ordinary level of sociology. She may be genderless, but that sure as hell doesn’t mean she was androgynous, androgyny being, on some basic level, a denial of sex. Dietrich’s photos are redolent of sex, but sex that refuses to take a side, to give up either masculinity or femininity, and thus stripped of the predictability, the sense of sexual manifest destiny, that hovers around all sexual archetypes. Of course, surrender can never be exorcised from our reaction to movie glamour. We see and respond to those images with an intensity that strives to meet their enormous scale. Part of the appeal of movies is losing ourselves, of swimming in the image, drowning in it and still being able to breathe. And it’s that temptation of total immersion, a baptism into a sensual rather than a sacred realm, that calls from the pages of this book. For all that I can say about my preferences when it comes to the Dietrich look, I’m not going to pretend that I can escape the allure of the photos collected here. What am I to do? I can’t help it.