Within minutes after the collapse of the World Trade Center, inspirational songs, propagandistic images designed to feed the fires of patriotic fury, and poetry commemorating the victims began to proliferate on radio, television and the Internet. The Dixie Chicks performed an a cappella rendition of “The Star Spangled Banner”; car-window decals appeared featuring a lugubrious poodle with a glistening tear as large as a gum drop rolling mournfully down its cheek; refrigerator magnets of Old Glory flooded the market (“buy two and get a third one FREE!”); and the unofficial laureates of the World Wide Web brought the Internet to a crawl by posting thousands of elegies with such lyrics as “May America’s flag forever fly unfurled,/May Heaven be our perished souls’ ‘Windows on the World’!” Gigabytes of odes to the lost firemen and celebrations of American resolve turned the information superhighway into a parking lot:

My Daddy’s Flag

Arriving home from work and a trip to the store,

My 5 year old daughter greeted me at the door.

‘Hi daddy!’ she smiled, ‘what’s in the bag?’

‘Well, daddy has brought home the American flag.’

With a puzzled look she asked ‘What does it do?’

I answered, ‘it’s our country’s colors, red, white and blue.

This flag on our house will protect you my dear,

It has magical powers to keep away fear.’

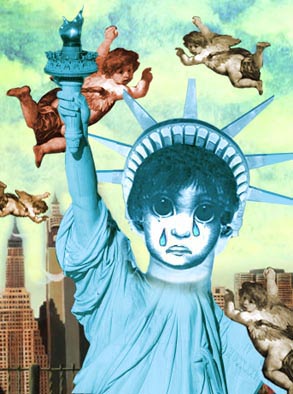

Does an event as catastrophic as this one require the rhetoric of kitsch to make it less horrendous? Do we need the overkill of ribbons and commemorative quilts, haloed seraphim perched on top of the burning towers and teddy bears in firefighter helmets waving flags, in order to forget the final minutes of bond traders, restaurant workers and secretaries screaming in elevators filling with smoke, standing in the frames of broken windows on the 90th floor waiting for help, and staggering down the stairwells covered in third-degree burns? Perhaps saccharine images of sobbing Statues of Liberty and posters that announce “we will never forget when the Eagle cried” make the incident more palatable, more “aesthetic” in a sense, decorated with the mortician’s reassuringly familiar stock in trade. Through kitsch, we avert our eyes from tragedy, transforming the unspeakable ugliness of diseases, accidents and wars into something poetic and noble, into pat stories whose happy endings offer enduring lessons in courage and resilience.

And yet while kitsch may serve to anesthetize us to the macabre spectacle of perfectly manicured severed hands embedded in the mud and charred bodies dropping out of windows, it may conceal another agenda. The strident sentimentality of kitsch makes the unsaid impermissible and silences dissenting opinions, which cannot withstand the emotional vehemence of its rhetoric. It not only beautifies ghoulish images, it whitewashes the political context of the attack which, when portrayed as a pure instance of gratuitous sadism, of inexpiable wickedness, appears to have had no cause, no ultimate goal. Four months to Bush’s “crusade,” despite clear successes, we remain far from certain about what, in the long run, we hope to achieve.

Ignoring geopolitics, we sealed the incident off in an ideologically sterile vacuum, the perfect incubator for kitsch, which thrives on irrational simplifications of moral complexities. Rather than making sincere efforts to understand the historical origins of the event in a protracted international conflict, we erect a schematic narrative that pitted absolute evil against absolute good, our own unwavering rationality against the delirium of crazed fanatics. On the electronic bulletin boards on the Internet, the terrorists became cartoon villains whose “insane and beastly acts” were both unmotivated and unaccountable, the result of nothing more explicable than “malevolence,” of the “dastardly cowardice” of “an inhuman … group that has no place in the universe.” These “depraved minions of a hate-filled maniac” who subscribed to “the toxic theology [of] suicidal barbarism,” “watched from a distance/And laughed in a hauty [sic] tone” at this “ungodly intrusional [sic] violation of human life,” this “psychotic” prank ostensibly staged out of sheer spite.

If the perpetrators are monsters, the victims are not just innocent but angelic, diaphanous seraphs with harps who, after being crushed in the collapse, “rose again,/Through the smoke, and dust and pain./To fly. To play above again/In the blue American sky./The perfect, blue American sky.” R&B vocalist Kristy Jackson has hit the charts with a commemorative single entitled “Little Did She Know” about a woman who, on the morning of Sept. 11, sent her fireman husband off to work with a peck on his cheek, heedless of the fact that he would never return:

Little did she know she’d kissed a hero

Though he’d always been one in her eyes

But when faced with certain death

He’d said a prayer and took a breath

And led an army of true angels in the sky

Little did she know she’d kissed a hero

Though he’d always been an angel in her eyes

Putting others first, it’s true

That’s what heroes always do

Now he doesn’t need a pair of wings to fly

The kitsch of extreme innocence also emerges in the selectivity of the roll call of the martyrs. We found the deaths of the emergency personnel far more riveting than the deaths of the office workers, even though the latter outnumbered the former by a ratio of approximately 12 to 1. It is difficult to make a martyr out of someone who is run down in the street by a bus, as the casualties in the two buildings essentially were, dying, not while manning gun turrets or lobbing grenades, but while filing expense reports and faxing spreadsheets. Such an unglamorous, clerical fate is not suited to instant martyrdom and hence our attention shifted away from secretaries and CEOs, who did nothing more intrepid than attempt to save their own lives, and gravitated toward a group that more adequately satisfies our folkloric requirements for heroism. The whole story was reshaped so that the narrative focus fell squarely on those whose bravery in the face of death allowed us to superimpose on the chaos and panic of that incomprehensible hour a reassuring bedtime story of valiant knights charging into the breach, laying down their lives for their countrymen as they fought against “the forces of darkness.”

Much as the skies above New York were immediately “sterilized” to prevent further attacks, so debate was sterilized to prevent further discussion of the disaster. Many patriotic stalwarts seemed to believe that dissent amounted to a disavowal of one’s American citizenship, a McCarthyite accusation that created an atmosphere of fear and paranoia, a self-consciousness hardly conducive to the effective discussion of an emergency. Moreover, uncritical defenders of our foreign policy made liberal use of such words as “tasteless,” “inappropriate” and “untimely” to describe the statements of anyone who questioned the wisdom of carpet-bombing Afghanistan, including the unfortunate host of the television program “Politically Incorrect,” who was forced to retract remarks deemed offensive to the Pentagon after his outraged sponsors, Sears and Fed-Ex, summarily yanked their advertisements. Because other more despotic forms of repression have been outlawed in democracies, we now rely heavily on a lawful form of censorship, social pressure, a subtle method of coercion that legislates conformity by stigmatizing marginal opinions as the indiscretions of ill-mannered boobs who, while they may not literally break the law, trample on the more elusive statutes of “decency.” It is ironic that, during a time in which we seem so preoccupied with the “tastefulness” of people’s remarks, we exhibit an appalling insensitivity to the tastelessness of kitsch, which repeatedly and unapologetically rides roughshod over all aesthetic standards.

Instead of conducting open and uninhibited discussions, we state our opinions through symbols, through saber-rattling images of American eagles sitting on stools sharpening their claws; screen savers of rippling flags captioned “these colors don’t run”; computer-manipulated photographs of the tear-streaked face of the Man of Sorrows superimposed on the Statue of Liberty; and votive candles that morph into the burning buildings themselves. It is appropriate that President Bush, a man known for the endlessly inventive infelicities of his speech, should communicate to the American public largely by means of symbols, by displaying the badges of dead policemen and staging photo-ops in which, bull horn in hand, he hugs firemen on piles of rubble and leads squirming first-graders in the Pledge of Allegiance after admiring a bulletin board of their drawings titled “The Day We Were Very Sad.”

Symbols are the language spoken by those who are uncomfortable with words. Our leaders use them when they seek to stimulate, not thought, but adrenaline. They are the weapons of emotional obscurantism, paralyzing dialogue before we are plunged into war where doubts and hesitations have potentially disastrous consequences and where our actions must be swift, decisive and unthinking. So much of the “discussion” of the World Trade Center is based on button-pushing, on a barrage of symbols designed to trigger reflexive, Pavlovian reactions, bringing us to our feet against our wills to salute the flag and burst as one into song, our intellectual independence shot down by salvos of patriotic kitsch.

In the course of the imagistic orgies that flared up after Sept. 11, a brand new American symbol was invented: the towers themselves. Poets and commentators anthropomorphized the skyscrapers as, on the one hand, “pillars of strength,” which, like Atlas, seemed to support the weight of the entire United States; and, on the other, as wavering ghosts, which, like Hamlet’s murdered father, seemed to call out for revenge, especially when they were superimposed on top of sympathy card images of disconsolate angels. The buildings quickly lost their material reality as architecture and became living beings, “two brothers” endowed with the capacity to move, to “reach,” “stretch,” and “stand tall.” We even cast this prime piece of Manhattan real estate as Christ in a resurrection scene: No sooner do the buildings collapse than, like phoenixes, they rise again from their ashes, often in the form of the American eagle, soaring skyward out of the smoking rubble: “As the Eagle lay on the ground In awe I witnessed a miracle, a rebirth! The eagle rose triumphant.”

The transformation of the Word Trade Center from a physical location into a turn of phrase, a “vibrant symbol of the bounty and pride of democracy,” gave both terrorism and dissent a new dimension, that of heresy, of the desecration of holy idols, of buildings that quickly acquired the mystique of temples and, in many images, of New Age crystals, which, like gigantic prisms, emanated a throbbing aura of iridescent energy. As a result, those who advocated restraint became more than just opposing voices but iconoclasts and flag-burners, blasphemers who inflicted physical harm on objects that our high-flown rhetoric treated as sacred relics. We left the realm of reason, of bricks and mortar, and entered the realm of faith, of sacraments and graven images, of flags that have “magical powers to keep away fear.” We scoff at the extremism of terrorists who are willing to die in the name of Allah, but we ignore the religious dimension of our own behavior which we justify not by carefully reasoned defenses but by animistic symbols as hallowed as the Koran or the Kaaba. Both the Islamic fundamentalist and the American patriot may share more than they care to admit.

Economic as well as political factors contributed to the proliferation of kitsch after Sept. 11. Kitsch is frequently associated with fundraising, especially fundraising for diseases that afflict children, whether it be the doe-eyed poster children of the first muscular dystrophy campaign, or Ryan White, the heroic young AIDS victim who, after being railroaded out of his bigoted hometown, was canonized as the patron saint of AIDS charities, largely by means of the attention lavished on him by People magazine. And yet, appearances notwithstanding, AIDS affects far fewer children than it does adults. Similarly, on Sept. 11, only three victims were below the age of 13 (all passengers on the hijacked planes). That’s a surprising statistic, given the disproportionate number of relief agencies that, after the attacks, were launched specifically to help children, the cash cows of the tragedy’s nonprofits, which have primed the pumps of American generosity with ad campaigns featuring images of bereft toddlers superimposed on apocalyptic photographs of the ruins. Even during an event in which children are only indirect casualties, they are the ones brought in to shake the tin cans. They, and not adults, are easiest on the eyes, the most photogenic of panhandlers, issuing importunate entreaties with a mere kiss on the cheek or squeeze of the hand. Children are the unpaid workmen of kitsch, its drudges and slave laborers. Many did, of course, lose a parent, but many parents lost something equally important: their lives. Once again, the primary victims of the tragedy were shuffled off to the sidelines to make room for a cast of more narratively appealing objects of compassion, much as the rescue workers were elevated into the starring roles of this “Towering Inferno,” since their deaths were more dramatic than the banal denouements of file clerks collapsing at the water cooler and stock brokers suffocating in bathroom stalls.

What distinguishes the professional fundraiser from any other sort of commercial advertiser is that he has nothing to sell other than his complimentary toasters and his tote bags, his “Never Forget” T-shirts and his American flag car window clings. Because the altruist receives nothing commensurate with the money he gives, nonprofit organizations must ensure that they provide an adequate emotional boon to their benefactors, an intangible feeling of pride, a “warm glow,” the sole “product” that the fundraiser really “sells.” Charities must induce the consumer to do something that goes against his capitalistic instincts, to give something for nothing, a dilemma that leads them to employ the full rhetorical arsenal of kitsch, providing a particularly rich and satisfying spiritual reward in the complete absence of a material one. Charities are so kitschy precisely because they are an industry that packages the warm glow, the well-earned satisfaction we experience after limping to the finish line of an the AIDS walkathon sponsored by AmFAR or adopting a wide-eyed Central American waif through the Save-the-Children Fund.

But in the midst of epidemics and natural disasters, many Fortune-500 companies try to pass themselves off as charities, to slip into wallets already lubricated by the grease of legitimate, fundraising kitsch, such as Burger King, which is helping to “rebuild the American way of life” by selling $1 flag decals with their shakes and fries. After Sept. 11, the airwaves were flooded with corporate condolences from firms that should perhaps have donated to the FDNY’s Widows and Orphans Fund the millions they squandered on prime-time television spots advertising their good Samaritanship, expressing their “horror,” and dispensing their “thoughts and heartfelt prayers.” Charity impersonators infiltrated the ranks of the Red Cross and the Twin Towers Fund, camouflaging their commercials as public service announcements, while hordes of unscrupulous entrepreneurs set up shop by promising to donate to the orphans of dead firemen 20 percent, a full one-fifth, of the proceeds they collected from the sale of their WTC coffee mugs and their “United We Stand” posters of the towers wrapped like an enormous Christo work in 110-story flags (“please support our country, every purchase helps. God Bless America”). Even a pornographic Web site that offers paying clients images of big-busted Asian women promised to donate 10 percent of its proceeds to relief agencies.

If there was something duplicitous about Wendy’s asserting its intentions of selling hamburgers to make “our beloved nation stronger than ever,” Coca-Cola blowing its own horn about the fruit juices it supplied the rescue workers, and Chase Manhattan Bank hanging a four-story American flag on the facade of its Midtown offices, there was something equally duplicitous about the consumers who responded to these blandishments and shopped up a storm under the thin pretense that, given a company’s outpouring of concern, they were “giving” rather than “buying,” donating their hard-earned dollars to a caring, compassionate organization that offered something a little more enticing than a thank-you note, a toaster, and a tax break. We discovered that we could have our cake and eat it too, enjoy that laptop or that surround-sound stereo system and simultaneously bask in the warm glow. If corporations engaged in charity impersonation, consumers engaged in a similar fraud: benefactor impersonation, with both parties participating in a mutually beneficial game of self-flattery.

The marketing of self-congratulation finds a particularly susceptible consumer niche in a culture permeated with pop psychology, with its ever-more clamorous calls for emotional candor and its dire warnings about the dangers of bottling up potentially explosive feelings of anger, pain and grief. Soon after the attack, Oprah’s Oxygen Media posted on its Web site a video of Cheryl Richardson, a self-styled “life coach,” who advised viewers to “get your feelings up and out of your body in order to assist in the healing process,” as if our emotions were toxic substances or medieval “humours,” which exert damaging pressure on our internal organs, poisoning our systems if they are not purged or drawn out by professional blood-letters. Throughout the crisis, the constant refrain of politicians, celebrities, and even housewives was the necessity of beginning the process of “healing,” which, in the current context, has nothing to do with recuperation, but precisely the opposite: with wallowing, indulging in the unnecessary prolongation of our misery, in the drama of living in a state of high alert.

What’s more, the word “healing” promiscuously extends the status of victim to the general public and hence the privilege of being coddled, consoled and pitied, as if we were all casualties and had all narrowly escaped being crushed in the collapsing towers, rather than merely sat safely in our living rooms glued to our television sets.

The mandate to “allow yourself to cry the wounded animal sounds and write in your grief journal,” to quote one of several mourning “rituals” Oprah offered her audience after Sept. 11, shows how the contemporary notion of mental health has weakened the inhibitions that once held our sentimentality in check, our sense of shame about self-disclosure, about losing control in public. We have reached unprecedented levels of mawkishness, levels that exceed even those attained by such lachrymose Victorians as Dickens and his devoted readers who wept copiously over the untimely death of Little Nell, a tragedy that would appear to bear some resemblance to the Sept. 11 attack, which, according to one commentator, was so moving that it “burst the clogged, stereotypical male tear duct wide open.”

Our belief in the putative healthiness of creating external embodiments of internal states through “art” and “play” therapies, activities that lead to a proliferation of folk ceremonies and homemade tchotchkes: commemorative quilts, the largest hug ever staged in human history (thousands linked arms in a field after the tragedy), and the work of the so-called “Crayola Coalition,” a group of school children nationwide who commit their hopes and fears to paper and send them to the rescue workers (often with the help of McDonald’s, which includes original artwork — surely an indication of how highly such drawings are prized — in each bag of Big Macs and French fries it distributes at ground zero).

We are now taught that it is detrimental to our peace of mind, indeed, to our sanity, to experience emotion apart from its communication, its “release,” and must therefore never remain alone with our feelings but seek out an audience to receive our discharges, our cathartic unburdenings, the messy, unhygienic ruptures of our blockages. What we are witnessing in the kitschification of the World Trade Center is how the pressure to externalize, to emote, “to get your feelings up and out of your body” results in emotional exhibitionism, emotional pornography, a need to play to the galleries and ham up our shock and horror as histrionic spectacles that we relish in and of themselves. Internal states retain their authenticity only if they retain some of the solitude in which they are originally experienced, only if there is no audience that needs to be entertained by the trembling of our chins, only if our real responses remain inaccessible to others in the privacy of our consciousness.

The Internet bulletin boards provide one of the most unrestrained examples of the emotional exhibitionism that pop psychology sanctions. The anonymity of the Web eliminated any need for a censoring mechanism to contain the exuberance of our grief and the result was a crying contest to see who could utter the loudest lamentations, the most piercing keens:

“I felt … disbelief, horror, sadness, and the relentless shedding of tears … Would I ever be able to enjoy a sunrise again? … Would food ever taste good to me again?”

“I flipped the tv to the news early Tuesday while putting a workout video in the vcr … needless to say, i never did work out that day … Every time i hear or see the news, i cry … the flags flying all over my city make me cry … hearing our national anthem through various media makes me cry … hearing people going around trying to find their loved ones makes me cry … knowing how many lives were directly affected … makes me cry … i’ve been crying since Tuesday.”

When the crying subsided, bulletin board contributors offered each other a profusion of papal blessings (“may God bless each & every one of you,” “may the Lord cause His Countenance to shine upon you”) and engaged in one of the most complex and disingenuous acts of mourning seen in the aftermath of the World Trade Center tragedy: They posted condolences to the victims’ families, electronic sympathy cards in which they told the orphaned children of firemen that “I just wanted you all to know I cared” and wrote poetry to the bereaved husbands and wives and despairing mothers and fathers:

“We care that you are lonely and blue,

So we are sending this hug especially for you.”

One unnerving thing is missing from this soothing murmur of comforting words: the people being comforted. It is doubtful that the survivors of the tragedy spent the hours after Sept. 11 poring over the thousands if not millions of notes that appeared on the Web and one must therefore conclude that we posted them for our own benefit, that we were both the senders and receivers of these love letters, and that we took turns playing for each other an audience of devastated widows and orphans. We were acting as aesthetes of grief, competing to see who could utter the windiest sighs, who could beat their breasts and gnash their teeth most piteously. Kitsch was created as the ante was steadily upped and the emotional pornography of an exhibitionistic culture reached its climax, its money shot. Just as Puritans once vied with each other in demonstrations of their piety, so we competed to prove who could feel the most, who could “express” the most intensely, showing off a new type of secular piety as unctuous as the zealotry of 17th century religious purists.

The Internet samizdat offered not only a talent contest for the self-appointed pallbearers of the tragedy but an art gallery in which grass-roots designers displayed their click-and-drag doodles and daubs. The images in this electronic museum are based on what might be called the aesthetic of jumble, the haphazard look that results when preexisting images available in such computer programs as Clip Art are carelessly juxtaposed or even rendered transparent and placed on top of each other, forming an arty if often illegible mess. With a click of the mouse, files can be copied and pasted so that the same American eagle can be endlessly recycled and combined in countless permutations with the same angel, the same candle, the same red-white-and-blue ribbon, and the same dove carrying the same olive branch. The deadening unoriginality of Internet kitsch is largely the result of the computer’s capacity to clone pictures and photographs, thereby minimizing the user’s need to invent his own graphics and reducing his role to that of a collector, the rag picker of the World Wide Web who scavenges through various databases in order to assemble a collage of ready-made imagery.

The aesthetic of jumble and the prefab look that it creates become a metaphor of the intellectual vacuity of the Internet samizdat where opinions are replicated and then pasted in like Clip Art, the same denunciations of the terrorists’ “evil” appearing cheek-by-jowl with the same panegyrics of the firemen’s selfless heroism, the same expression of American indomitability with the same torrential spate of tears. As an experiment in democracy, the Internet has failed, for while it is true that the voiceless may have found their voices in a forum in which it is always open-mike and people are free to say virtually anything they’d like, in fact they do little more than repeat the clichis of their leaders, mouthing slogans that are the literary equivalent of the graphics created in the wake of the attacks. The photo-ops of President Bush and the inflammatory symbol-mongering that has dominated the discussion of the attack become the editorial Clip Art of the bulletin boards, the source of the generic patriotism and jingoistic hawkishness that the contributors right-click and copy, presenting them to the public as revelations. Much is made of the radical potential of the Web, which has restored to common people the means of being heard above the deafening corporate voices of the media, but when we really listen to these quieter, uncensored voices, what we hear is smiley faces and little red cabooses, Santa Clauses and carved pumpkins. The Internet is the grave of free speech, a monument to our lack of thought and autonomy. Freedom to speak amounts to freedom to repeat, to select a pictograph from an archive of icons, here a whimper of stereotyped anguish, there a defiant cry of militaristic fury.

The same voice echoes from server to shining server. The response to the World Trade Center attack was a celebration of consensus, of the exhilarating unanimity of what one bulletin-board contributor aptly characterized as “Americans banning [sic] together, soaring [sic] flags, showing pride.” People from every corner of the globe weighed in with their expression of sorrow and solidarity, from the residents of “the little inupiaq Eskimo village on the shores of the Bering Sea in Deering, Alaska” to the Australian chapter of the Jackie Chan Fan Club: “on behalf of the member of the Australian Jackie Chan Fan Club, our thoughts, prayers, and hearts are with all of our brothers and sisters in the United States.”

Within a matter of days, memories of the tragedy seemed to fade as horror gave way to the unadulterated joy of togetherness, which lent the bulletin boards an air of morbid conviviality, the stately funeral procession quickly lapsing into a riotous Irish wake. “How I wish I could embrace you all!” one contributor bursts forth, while another shouts “we love you all!!!” and still another recommends hugging as a palliative to grief, for “a hug heals more pain than the eye alone can see.” One contributor was so overwhelmed by the spirit of good will created by the tragedy that she wrote a poem in which she imagined the victims of the attack “choosing” to die in the World Trade Center well before their birth, volunteering in heaven for a divine mission, that of rallying all nations together in a common cause against evil:

“In the halls of Heaven an offer

was made to thousands

of angels one day:

‘You can go to the earth and help unite the world

But you won’t be able to stay.’

The angels stepped forward.”

Behind the kitsch of our grief is a horrible, seemingly inhuman fact: We are not as dejected as we profess but in fact excited, a repulsive notion that we hide from ourselves, burying our euphoria deeper and deeper in sentimentality, becoming all the more long-faced the more gleeful we are at having come together as one.

Why do we experience pleasure during such crises? Surely not because we are sadists at heart, prurient, unfeeling ghouls who gloat over the sufferings of others. Instead, such an inappropriate reaction is the natural outcome of the fact that we no longer consciously experience on a daily basis a very acute sense of belonging to any community, even though the infrastructure of a highly complex society lies behind our most insignificant actions, from opening a tap and raising the thermostat, to flushing a toilet and flipping on a light. And yet, the communities we live in have become invisible, despite their omnipresence; the thousands who work in our water departments are never seen, we have no contact with those who keep our furnaces running, and the electric company appears only when the meter reader rings our bell. What’s more, our government operates so efficiently that it has all but disappeared from our lives, leaving us with an eerie sense of being free agents acting alone in an unpopulated wilderness full of automated amenities. A society that seems to run by itself, that does not require us to perform any civic duties, is plagued by feelings of isolation and is particularly prone to bouts of pathological collectivity in which we hold old-fashioned neighborhood socials around a centerpiece of mangled corpses, a hideous incongruity that we hide behind a tearful mask of kitsch. In an atomized society, any crisis becomes a catalyst for instant togetherness in which the pleasure of companionship far exceeds the depths of sorrow and our fierce tribal instincts reemerge with a vengeance, having been thwarted by the curse of autonomy that afflicts advanced Western cultures.