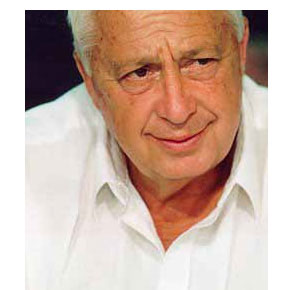

Ariel Sharon is a great believer in secret diplomacy. He is also a shrewd politician. The Israeli prime minister used both secrecy and shrewdness in the past week, fending off domestic political opponents on his left while simultaneously burnishing his scanty credentials as a man of peace on the eve of a trip to Washington, where he is scheduled to meet President Bush on Thursday.

A year after his landslide election victory, Sharon has yet to show a single achievement, aside perhaps from the growing isolation of his lifelong nemesis, Palestinian leader Yasser Arafat. But as much as it dislikes Arafat, the Israeli public cares more about its own well-being, and there is no good news on the domestic front. No end is in sight for the bloody semi-war with the Palestinians, and the national consensus over the fight was broken recently when more than 100 army reservists announced their refusal to serve in the occupied territories and condemned army practices there. The Israeli economy is in a shambles, with no hope seen for improvement. And while Sharon is still riding high in the weekly opinion polls, he is facing growing public, political and media criticism for his perceived lack of leadership and initiative.

On the diplomatic front, too, there have been troubling recent developments. The Bush administration has largely embraced Sharon’s hard line on the Palestinians and Iran. But though Bush censured Arafat harshly after Iranian arms intended for the Palestinian Authority were seized, he disappointed Sharon by not completely breaking with the Palestinian leader. And though the Americans have suspended envoy Anthony Zinni’s peacekeeping mission for now, they’ve made it clear that they expect the prime minister to come up with a plan for how to get out of the mess. The European Union, traditionally more pro-Arab than the United States, broke ranks once again with its American allies and issued a statement of support for Arafat last week, weakening the united international front against him.

Domestically, Sharon faces challenges from Foreign Minister Shimon Peres and Defense Minister and Labor Party chairman Benjamin Ben-Eliezer (who is known in Israel as “Fuad”). The two Labor leaders, who hold the most important portfolios in Sharon’s national unity coalition, are working on rival peace plans — and Ben-Eliezer is also a formidable political opponent of Sharon’s.

Confronted with this set of problems, who did Sharon turn to? Yasser Arafat.

Last Wednesday night, Sharon invited three top Palestinian officials to have dinner at his official residence in Jerusalem. The small group around the table included Abu Mazen (the nom de guerre of Mahmood Abbas), No. 2 in the Palestinian hierarchy; Abu Ala (Ahmed Qurei), speaker of the Palestinian legislative council; and Mohammed Rashid, Arafat’s financial advisor and personal confidant. Abu Ala has been negotiating a peace plan with Peres. Also present at the dinner was Omri Sharon, son of the prime minister, along with Sharon’s bureau chief, Uri Shani, his military advisor, general Moshe Kaplinski, and his appointed negotiator, retired general Meir Dagan.

By meeting with the top lieutenants of his archenemy, Sharon achieved three things. He outmaneuvered both Peres and Fuad, preventing them from claiming that they were making real moves toward peace while he stonewalled (although by doing so he exposed himself to attacks from the far-right camp of former Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu). He shored up his support with the Israeli public by keeping his promise to meet with the Palestinian leadership when the time was right. And he signaled to the Bush administration that he was prepared to bring something to the peace-talks table.

Sharon’s dinner with the senior Palestinian leadership was a classic of political zigzagging even by Middle East standards, where yesterday’s hated enemy is today’s working partner. Only a few hours before breaking bread with Abu Mazen, whom Arafat calls “my brother,” Sharon had told an Israeli newspaper that he regretted not ordering an Israeli sniper to kill the PLO leader when he was being evacuated from Beirut in 1982 “because we promised not to do so.” In another interview on the same day, Sharon said that his advice to Bush was to simply ignore Arafat.

But Sharon ignored his own advice, secretly reaching out not only to Arafat’s aides, but to Arafat himself. The night before, Arafat received a rare Israeli visitor at his Ramallah headquarters, under the gun barrels of Israeli tanks. The guest was Yossi Ginossar, an Israeli businessman and former high security official. Since his first meeting with Arafat in 1985, Ginossar has been the Israeli to whom the Palestinian leader is closest, and successive prime ministers have used him to pass messages back and forth. Sharon tried to avoid using Ginossar for a while, instead sending his son Omri to meet with Arafat. But last week, the veteran war horse was called back to action, first to brief Sharon on the inner workings of Arafat’s circle, and then to go to Ramallah.

(Just who the go-between was who initiated the meeting is disputed. According to Palestinian sources, it was Ginossar; Sharon’s office said it was Omri. Either way, the delegation could not have met the Israeli leader without Arafat’s consent.)

The meeting scored political points for both Sharon and Arafat. Arafat proved he was still an indispensable player and revealed holes in the Israeli blockade against him. Sharon could say that he spoke with “pragmatic Palestinians,” while continuing to insist that Arafat is “irrelevant” and should be kept “under extreme pressure.”

Substantively, Sharon offered nothing very new at the three-hour meeting. After an open-ended armistice or period of “non-belligerency” during which both sides would have to fulfill a “table of expectations” in order “to test the relationship,” final peace talks would begin. His final plan, as published before, calls for the creation of a Palestinian state in the current “autonomous” area of the occupied territories, with some added territory for “contiguity.” He avoided getting into details, Sharon said. During the long-term armistice period, the Israeli settlements in the West Bank and Gaza would remain in place, and Israel would hold large “security zones” on both edges of the West Bank. Meanwhile, economic cooperation and foreign investment would raise the Palestinian standard of living, thereby reducing nationalistic fervor. In other words, Sharon’s plan would freeze the status quo for a long time, with a larger symbolic independence for the Palestinians. In the longer term, it would offer the Palestinians significantly less than former Prime Minister Ehud Barak offered them at Camp David and Taba. Sharon has insisted on not revealing more about his plan, repeatedly arguing that “whatever I say would become the opening line for more demands and concessions.”

The Palestinian participants told Israeli friends that their host was open and sincere. But, not surprisingly, no progress was made. Each side presented its demands, and there was no agreement on how to end the violence and return to the negotiating table. Both sides were waiting for the other to make the first move, the first serious concession.

For his part, Peres still hopes the breakthrough will come from his negotiations with Abu Ala. Their proposal is to create a Palestinian state in the current autonomous areas, shortly after a cease-fire is reached. (Sharon’s plan, by contrast, insists that a state would come only “at the end of the process.”) The newborn state would then negotiate its borders and other final-status issues with Israel. While Peres was flying across the Atlantic to the World Economic Forum in New York, Sharon was telling the Palestinian leadership that the Peres plan was unacceptable to him. But ever the optimist, Peres still hopes to overcome Sharon’s reservations, seeking support from the international community in his New York meetings.

The catalyst for Sharon’s visit to Washington was not Peres but Ben-Eliezer, the defense minister whom Sharon thought at first to be a lightweight but who has turned out to be something of a headache for him. Upon his election to the Labor Party leadership last month, Ben-Eliezer called for an early election in November, a year ahead of the term limit. An early election is the last thing Sharon wants: To get there, he would have to face a political life-or-death match with his Likud Party challenger, Netanyahu, who would likely win. Peres, on the other hand, shares Sharon’s preference for a later election. The elder statesman, who turns 79 this summer, is unlikely to run again for office.

On Jan. 10, Sharon was surprised to read in the newspaper that Fuad was preparing a new diplomatic plan, which he would present to the Bush administration during a planned visit to Washington in early February. The new plan would show Ben-Eliezer as a moderate, willing to be more flexible in negotiating with the Palestinians than Sharon is. It would also serve as a platform, or pretext, to pull Labor out of Sharon’s government before the election.

The prime minister smelled trouble. At a private conversation that same day, he confided: “I’m more worried about Fuad than Peres. I’ve known Peres for 50 years. We have our disagreements over policy, but we can work together. I know how to deal with him. Fuad is another matter, he’s got ambition.”

Sharon decided to beat Ben-Eliezer and Peres to the punch and come to Washington himself (although his office said that Bush had initiated the trip). To arrange the meeting, Sharon used his back channel to the administration, New York-based businessman Arie Genger, an Israeli-born industrialist and one of the prime minister’s closest friends and contributors, who speaks regularly on the phone with Secretary of State Colin Powell and National Security Advisor Condoleezza Rice. Genger reports directly to Sharon, bypassing the leaky diplomatic machinery (which reports to Peres).

Ben-Eliezer was blindsided by Sharon’s wily move, and was furious when he learned that the prime minister’s visit would coincide with his own. His hopes for his own presidential quality time were dimmed, and he had lost his chance to present himself as the new alternative to Sharon.

While Sharon was stealing a march on his rivals at home, the Bush administration was tilting toward Sharon’s hard line on Arafat and the Palestinians. The crucial event was the Israeli seizure on Jan. 3 of the Karine A, a ship loaded with Iranian arms intended for the Palestinians. Bush, who has refused ever to meet the Palestinian leader, was furious at Arafat for trying to obtain heavy arms and for deceiving him. He scheduled a meeting of top administration officials for Jan. 25.

According to Israeli embassy cables, the preparatory meetings turned into a major bureaucratic battle. On one side were the hawks, led by Undersecretary of Defense Doug Feith, who before joining the administration was an outspoken right-wing Jewish activist and an ardent critic of the Israeli-Palestinian peace process. Feith, with help from Vice President Dick Cheney’s office, wanted the U.S. to issue a fierce denunciation of the Palestinian leader. On the other side was the State Department, which traditionally is more sensitive to the concerns of America’s Arab and European allies. The hawks tried to take advantage of the absence of Powell and his assistant secretary for Near East affairs, William Burns, who were both out of town on diplomatic trips. According to Israeli reports, voices were raised, and Deputy National Security Advisor Steve Hedley had to calm everybody down.

The administration arrived at five conclusions after the discussions. First, the administration had failed so far in its attempts to deal with the Israeli-Palestinian crisis. Second, the U.S. had to be involved, or else its regional interests would be jeopardized. Third, Arafat had no credibility, but he was the sole authority on the Palestinian side, and so remained irreplaceable. Fourth, it was agreed that Israeli military actions provoked more Palestinian terror attacks. And finally, since it was not clear what America should do, it was recommended that the president somehow buy time — how was not made clear — while increasing pressure on Arafat to behave himself and fight terror.

No pressure on Israel to freeze settlements or stop its controversial retaliation practices was recommended. Special envoy Zinni’s mission, which was on hold anyway, was further postponed. And Bush, Cheney, Powell and Rice added a host of anti-Arafat rhetoric. The hard-liners had gotten most of what they wanted except the ultimate prize: a complete break with Arafat. Other rebuffed ideas included closing the PLO offices in Washington and putting some of Arafat’s own forces on the official list of terror groups.

When Powell and Burns returned to Washington, they fought back, calling for consultations with every interested party: Israelis, Palestinians, Egyptians, Jordanians, Europeans, Russians and U.N. officials. The air was filled again with diplomatic activity, a year after the breakdown of the peace process. The Arab allies, led by the Saudis, spearheaded a public relations blitz to rehabilitate Arafat. The Palestinian leader himself published a New York Times article renouncing terrorism and calling for a peaceful end to the conflict. (It received a skeptical reaction from Sharon, who basically said that talk was cheap, and Rice, who said that Arafat should now stay in Ramallah and do his job.) European Union officials proposed a new international peace conference, or a new election for the Palestinian Authority. The U.S. rejected both plans, but the Europeans warned the Americans to get more involved, or else they would go it alone.

Sharon arrives in Washington Wednesday night bruised by a recent budget battle in which his proposal for large budget cuts was shot down by his coalition partners. His foreign policy bag is full. He plans to ask Bush to increase pressure on Syria and Iran to stop supporting terror and halt their weapons programs. The Americans are expected to focus more on the Palestinian front.

Sharon believes that Arafat can’t deliver on any promises, and feels that the Americans and even Egypt share this view. He will tell the president that increased pressure and isolation of Arafat would eventually bring to power a new, more “pragmatic” Palestinian leadership that might be willing to negotiate the Sharon armistice plan. Whether the Bush administration will accept this view or will ask Sharon to take hard steps as well remains to be seen. “We agree with the administration on how to assess the situation with Arafat, but we have differences on how to deal with him,” a senior Sharon aide told me earlier this week. In the meantime, Sharon will promise not to harm Arafat physically and not to dismantle the Palestinian Authority. And, of course, keep meeting its top officials.