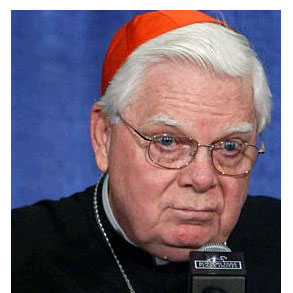

Boston has been outraged by the revelation that Cardinal Bernard Law knew of the many sexual abuse complaints against ex-priest John Geoghan for years, but shifted him from parish to parish anyway, and Boston Catholics are angriest of all. Yet Law shrugs off calls for his resignation. “Our faith doesn’t rest on the shifting winds of popular opinion,” the cardinal said, giving a beautiful example of the way Catholic Church leaders evade criticism on the pedophilia issue, while reiterating their lordly authority.

Note the language. It’s not Law or his decisions that are being questioned by detractors, it’s the Catholic faith itself, as if the two are the same thing. Many religious Americans may believe that the laws of God should take precedence over the laws of man — but most of them obey the laws of man anyway. The pedophilia scandal shows the extent to which the Catholic Church has been allowed to essentially ignore the law, and raises real questions about whether a true separation of church and state exists in America.

Whether Law will resign is still up in the air. What’s already clear is that he should be prosecuted as an accomplice in Geoghan’s crimes.

While the media has done some good work uncovering church sex abuse scandals, it’s done less well looking at the roots of the problem. Sensitivity about religion seems to blend with overall newsroom political correctness — we don’t want to make any group uncomfortable anymore — to mute tough questions as to what the scandal might tell us about Catholicism. Newsweek’s recent cover story on the child sex-abuse scandals is a case study. While it detailed the extent of the problem, it contained this boilerplate disclaimer: “Of course, priests have no monopoly on child abuse.”

Of course they don’t — men in all walks of life sexually abuse children, and the vast majority of priests are not child molesters. But the sentence also serves to minimize the problem. The sheer numbers involved in the recent scandals show that sexual abuse by priests is not a freak occurrence. Law turned over the names of 80 priests to authorities in Massachusetts; bishops in Maine, New Hampshire and Philadelphia have begun to follow suit. News of a cover-up in Tucson has come to light. Los Angeles’ popular Cardinal Roger Mahony is being pressured to turn over abuse complaints to the LAPD. And the National Catholic Reporter estimates the church has paid out more than $1 billion to settle sex-abuse suits in the last two decades (the U.S. Conference of Bishops insists the figure is closer to $250 million — still, not exactly a small sum).

Reporters have seemed reluctant to ponder the reasons for the prevalence of pedophilia among priests. Are pedophiles attracted to the priesthood because it gives them easy access to children? Do men with such sexual desires become priests seeking a way to curb those impulses? There’s something to be said for both positions. What seems clear is that, through a combination of its teachings on sexuality and its repeated willingness to shelter and cover up priest-pedophiles, the Catholic Church has created a safe haven for child sexual abuse, if not a breeding ground for it.

Asceticism plays a role in many religions of the world, not just Catholicism, of course. But it seems obvious that the risk of child sexual abuse is greater in a church that insists its clergy take a vow of celibacy. Insisting that priests cannot marry, let alone have sex, and then giving them power over the most vulnerable of beings — kids who are trained from birth to think of priests as God’s representatives on Earth (and thus almost unable to do wrong) — would seem to create the conditions for this scandal.

The church’s teaching that sin can be expiated by confession and sincere contrition may also play a role in allowing pedophilia to flourish. When crime is treated solely as a sin, there is nothing to prevent it from happening again. And when that crime is a sexual compulsion — which, as all compulsions do, follows a recurring pattern, with the need to act building up again after each release — it doesn’t matter how contrite the penitent is. Part of the thrill for sexual predators is the transgressive nature of their desires. What, for a child rapist, could be more thrilling than committing his crime in an atmosphere where the object of their desire is revered, bathed in blessed innocence?

These questions are missing from most mainstream media reports on the scandal. In fact, the liberal National Catholic Reporter has been braver than most secular media in suggesting that the church’s celibacy requirements mean the priesthood disproportionately attracts men with sexual problems. But whatever the reasons for priest-pedophilia, there is no mystery about what the Catholic Church did in Boston in response to years of charges against Geoghan. I honestly don’t understand why Cardinal Law hasn’t been charged as an accomplice in Geoghan’s crimes. The only justifiable answer can be that the Boston authorities are still in the process of gathering evidence.

Law, who has been Boston’s cardinal since 1984, has admitted that he knew of Geoghan’s pedophilia and, instead of reporting it to authorities or alerting parents in the parishes where Geoghan worked, he simply reassigned the priest — though he flat-out lied about that in the diocese’s newspaper last year. (The shuffling of Geoghan went on for 30 years. Law’s predecessor, the late Cardinal Humberto Medeiros, was also guilty.)

The facts about Geoghan became known only after the Boston Globe took the diocese to court to have the records on him unsealed. It was only this public revelation that prompted Law to turn over the names of other priests, more than 80 in all, who have been accused. When Law previously addressed the issue of how the church should proceed in cases of child sexual abuse in 1993, there was no mention of notifying authorities. Instead, priests have been sent to church-run “treatment centers,” again keeping these scandals under wraps.

Even viewed in the most charitable light, Law’s actions have been remarkably callous. How can he, or any Catholic official who has covered up allegations of abuse, be said to have demonstrated any Christian concern for his charges? His mealy-mouthed statements of regret (“We do not always make holy decisions, and we turn to God for the forgiveness he is always ready to give”) show no awareness that he should have to answer to any authority other than God, and confidence that there, at least, he will find forgiveness. In one statement he said that he is not like the CEO of a business. That is exactly what he is. As the head of a large division of a rich and powerful international organization, he must take responsibility for its decisions, especially the ones he makes. There is no reason to think that Law showed any more concern for the people in his care than did Enron’s Kenneth Lay (in fact, he sounds more like former CEO Jeffrey Skilling, parsing language to try to evade responsibility).

But Law is not alone. Cover-up has long been the church’s modus operandi when dealing with sexual abuse cases. The problem first made national headlines in 1984, when the story of a child-abusing Louisiana priest became news. In 1986, the National Conference of Catholic Bishops rejected the recommendation of a committee that the public be notified about priests who committed sexual abuse. Instead, to this day most cases are settled out of court and come with a gag order. The Newsweek story revealed that records are often shipped outside of U.S. jurisdiction to further protect the priests.

Finally, the law seems to be taking steps to end the extraordinary privilege the church has enjoyed in dealing with the pedophiles in its midst. On Feb. 26, the Massachusetts legislature passed a bill requiring clergy to report suspected cases of child abuse. California already has a similar law, and Los Angeles authorities have been questioning whether L.A.’s Cardinal Mahony has complied with it in the way he’s faced his diocese’s priest-pedophilia scandals.

What’s been oddest about the Boston case is that before the legislature’s vote, Cardinal Law had been under greater pressure from Catholics than he had from secular authorities. The 66-year-old Geoghan recently was sentenced to 10 years for one incident of assault. (Newsweek reported that there are 129 other potential victims.) But that’s not enough. In this case, as in all others where church officials knew of pedophile priests and didn’t make the accusations known to officials, those officials must be held legally culpable. There is no dispute about what Law did. His Eminence has very considerately detailed his prior knowledge of Geoghan’s crimes and provided the most damning evidence against himself. The question now is, do prosecutors in a largely Catholic city like Boston have the guts to put Law on trial, instead of bowing and scraping to him?

Certainly the laws vary from state to state, but there seems to be widespread national support for requiring people in care-giving professions to report evidence of a crime, especially child abuse. How is it that for so long, the church has escaped this trend and been allowed to make its own rules for dealing with pedophiles — rules that almost never include informing the police? Are the formation of those guidelines protected by the same violation of the separation of church and state that has provided us with the legal protection conferred on the confessional?

Finally the Massachusetts legislature has made it clear that church officials are legally obligated to report allegations of child sexual abuse. That’s a good first step. Now the authorities have to demonstrate that they are willing to act on clergy who cover up, no matter how high up in the church.

The church can go on insisting that pedophilia is a spiritual problem. But while its leaders prepare all they want to for the next world, they live in this one, and they have to obey its laws. A church that believed in the human sacrifice of children would not be allowed to carry out that practice. A church that has regularly sacrificed the souls and spirits of children to protect its public image has to suffer the consequences. It’s time for everyone involved to do their jobs. Leave the souls to Cardinal Law, and let the law have a shot at his flesh.