Until recently, most of the attacks against Israelis were carried out by radical Islamists from Hamas or Islamic Jihad. But now a new, secular organization has started taking credit for the bloodiest attacks on Israeli soldiers and civilians. They called themselves the Al Aqsa Martyrs Brigades, and they have become a crucial and little-known player in the bloody confrontation between Israelis and Palestinians. In an exclusive interview with Salon, Nasser Badawi, one of the group's senior commanders, talked about why the Brigades started, what its goals are, how it differs from Hamas and Islamic Jihad and what political developments could lead it to lay down the gun.

Israeli analysts initially belittled the Al Aqsa Martyrs Brigades as "armed gangs," but they have become a deadly force, inflicting enough casualties to rival the Islamists from the Hamas and Jihad movements combined. The brigades claimed a shooting in Netanya the same day in which a baby and one other person died. They also carried out Sunday's shooting attack in Kfar Saba in which a woman was killed. The brigades also claimed the suicide attack in an orthodox neighborhood in Jerusalem in which 10 people died just over two weeks ago, the same weekend as the checkpoint attack. In addition, they participated in the recent destruction of an Israeli tank.

The group evolved from the Fatah militia, long the guerrilla heart of the PLO. "But there were those of us who understood that with the Oslo Accords and the establishment of the Palestinian Authority the struggle had not ended," Badawi says.

The Brigades was founded in the Balata refugee camp some six months after the outbreak of the latest intifada (i.e. in spring 2001) as what Badawi says was "a reaction to attacks by the settlers and the brutality of the Israeli army." Badawi denies that Fatah made a conscious choice to try and take the initiative back from the Islamic groups Hamas and Islamic Jihad, who had taken the lead in attacks on Israelis after the first few months of the intifada. In this he differs from another Fatah leader, Marwan Barghouti, who heads the Tanzim militia. Barghouti said at the beginning of the intifada, "We were forced to take the initiative in the street if we didn't want to lose our leading position." Badawi sees it differently, saying "the resistance is open to everyone, we hope the others will join us."

(Tanzim is a Fatah militia, not part of the Palestinian Authority, which was mainly involved in the clashes during demonstrations at the beginning of the intifada. Tanzim is not generally associated with terrorist attacks, although its members sometimes fire at settlers. The exact difference between the different militias is murky and nobody knows what all the relationships are.)

Badawi paints a picture of the Brigades as issuing forth from grass-roots activists on the local level without any coordination with or instructions from the political echelon. Its members recognize Yasser Arafat and even Marwan Barghouti as leaders of the political movement, but "there is no direct relationship at all" between those leaders and the Brigades, Badawi maintains. (For its part, the Palestinian Authority has said little about the Brigades.)

Badawi says the Brigades are bound to obey the political leaders if they issue direct orders to desist, "but they haven't done so yet." Badawi is angered by suggestions that his outfit is a group of loose cannons outside the control of the political leadership and sometimes not in a position to gauge the real interests of the Palestinian people. "We are still Fatah," he exclaims. He views the armed resistance as merely a way to advance the political goals of the movement and insists that the Brigades keep a close eye on political developments. "When Arafat declared a cease-fire in December, we obeyed, not one week as they demanded but three weeks, and the Israelis only responded with more violence."

The Brigades militants do not share the hard line of the Islamic groups, which vow to destroy Israel: Al Aqsa members say that, like Fatah, they are interested in a peace process. They demand that Israel fully withdraw to its 1967 borders and, like Arafat and the P.A., also insist on the right of return of refugees to Israel, which would in effect mean the end of Israel as a Jewish state, if they are serious about implementing it and not simply putting it forward, as some believe, as a bargaining position. But if they are politically more conciliatory, their tactics are equally severe. They strike both civilian targets inside Israel and soldiers in the occupied territories. Lately the Brigades have even started copying the hitherto exclusively Islamist tactics of suicide bombings -- and because they are secular, they accept women as well. "Nationalist ideas are motivation enough, we don't need religion for that," Badawi says.

In the short term, in the wake of Israel's bloody incursion into P.A.-controlled areas, attacks against Israelis seem likely to continue. Members of Al Aqsa say they will not be mollified simply by Israel's withdrawal from the Palestinian territory it has occupied over the last couple of weeks. Revenge is a powerful motive: "blood for blood, a killing for a killing," says Badawi several times. The Israelis have not yet been made to pay fully for the Palestinian deaths they caused during their recent offensive, he states ominously. On the other hand, the Brigades keep an eye on political developments. Badawi says a cease-fire may be possible, "if it comes from both sides" -- which means if Israel drags its feet on political negotiations and insists that security and a cease-fire come first, their attacks will likely continue.

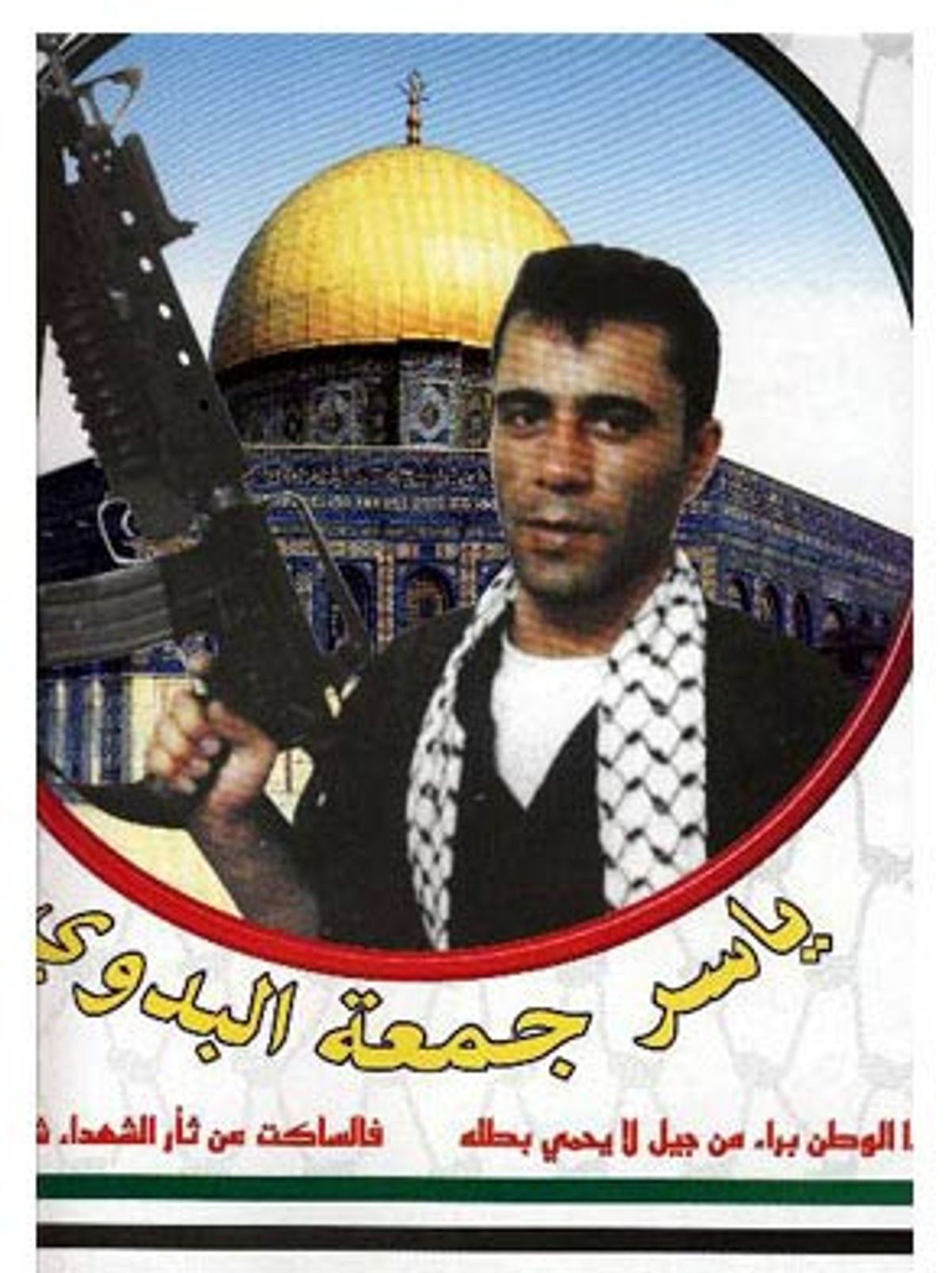

One of the Israeli practices that has to stop, he says, is the killing of Palestinian militants in so-called targeted assassinations. Badawi assumes he is on Israel's list of Palestinian militants marked for death and takes precautions. One of his offices is in a building used by civilians, which, he says reassuringly, will not be targeted by the Israeli guns and missiles positioned on the hills surrounding this West Bank town: "They wouldn't dare," he says. On the walls of the office, Yasser Arafat's portrait is the only one of a living person; the others are all legendary martyrs for the cause: the PLO's commander Abu Jihad, the PFLP's Abu Ali Mustafa and Nasser's younger brother Yasser, one of the founders of the Al Aqsa Martyrs Brigades.

Yasser was 30 years old when he died, the victim of an Israeli missile fired from a nearby hill, says his brother. The Israelis maintain he was killed in a so-called "work accident," shot by one of his own men. Yasser was a dyed-in-the-wool militant from the Balata refugee camp, a nationalist stronghold, whom the Israelis deported to Jordan during the first intifada.

The current round of fighting was sparked by the Israeli assassination of the Brigades' commander Raed Karmi in the West Bank city of Tulkarem, says Badawi. "Then we decided to hit inside Israel as well. The occupier doesn't understand anything except violence." The attacks are not only meant as revenge, he says: They are intended "to shatter Israeli society that has elected Ariel Sharon as its prime minister." The Palestinians know Israel's might and that it can attack anywhere at will, he says, but adds that now the Israelis are being made to feel "that we too can reach anywhere we want."

Badawi acknowledges that attacks inside Israel proper carry a political price, but he thinks they are worth it because they keep the Israelis off balance. Besides, from his point of view there is really no difference between attacks in the occupied territories and those inside Israel, since "they also attack our population." The tactic is working too, Badawi says: "They are afraid now." He is strengthened in that perception by recent concessions made by Sharon. The prime minister has given up on his demand for seven days of total calm before negotiations can resume. "It means nothing to us, it is an internal Israeli matter, but we do see it as a victory for our tactics."

The recent Israeli offensive against the Palestinians, in which the army invaded cities, villages and refugee camps, blew up houses, arrested thousands of people and killed hundreds, was totally ineffective, maintains Badawi. "They didn't arrest anybody important." Rather than hinder the Brigades, it helped them, he claims. "Because they hurt the civilian population we received even more support than before." He brags that the Al Aqsa Martyrs Brigades don't have a problem finding suicide bombers, or volunteers for "martyrdom operations" as the Palestinians call them: "They come in the thousands."

The Brigades will exact vengeance for the Israeli offensive, he says, but he remains deliberately vague about whether that will also be the case if the political leaders decide on a cease-fire. Even then, he says, "the Al Aqsa Brigades will remain active," though what that entails he won't divulge.

For the moment, Badawi believes there's no use even talking about a cease-fire, despite the Israeli withdrawal from Area A, where the Palestinian Authority is supposed to exercise full control. "There's nothing on the ground that indicates that the fighting will end -- not even Zinni can change that." He resents the cease-fire drive's focus on security: "We want political negotiations parallel with the security talks." For a commander of a military movement who says he has no direct contact with the political leaders, he toes the official line remarkably closely.

Badawi says he has little faith in Zinni's mission, because "the Americans are clearly biased towards Israel." He blames the U.S. for having given Sharon the green light for the all-out offensive against the Palestinians, and doesn't think that Washington has changed its attitude. He dismisses as window dressing the recent U.S.-drafted U.N. resolution calling for a Palestinian state, U.S. statements criticizing Israel, and the return of Zinni. "That is only propaganda, to please the Arab countries so that Cheney can pave the way for an American strike against Iraq." Badawi has kinder words for the Saudi Arabian peace initiative, although he criticizes its failure to mention the right of return for the Palestinian refugees.

The Al Aqsa Martyrs Brigades are not just an armed gang, Badawi says proudly: He insists that the group has clear political objectives. "We are Fatah people and we accepted Oslo. The problem is that the Israelis didn't stick to their word." He says that the Brigades are completely different from Hamas and Jihad, because "there is a different political vision. We are fighters but we hope to have peace."

The Brigades have become a force to be reckoned with, one that cannot be ignored in the run-up to a cease-fire and even during subsequent political negotiations. The question now is whether the Fatah-based group, having taken over the leading militant position in the intifada, will do as it says and obey the Palestinian Authority if it does decide to suspend the uprising -- or if, like Hamas and Islamic Jihad, it will decide to follow the path of war.

Shares