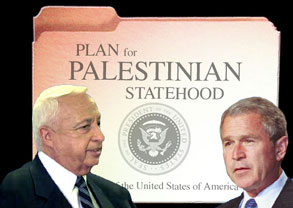

Israeli Prime Minister Ariel Sharon won a major diplomatic coup on Monday. In his long-awaited speech outlining America’s Middle East policy, President George W. Bush all but embraced Sharon’s views of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. The president’s position is strikingly similar to the talking points Sharon raised during his last visit to Washington, earlier this month. Like Sharon, Bush said the current Palestinian leadership must be replaced before any political dialogue could take place. Bush accepted Sharon’s refusal to negotiate with his lifelong nemesis, Palestinian leader Yasser Arafat.

In Israeli eyes, there is no mystery why Bush embraced Sharon’s line. Israeli intelligence has told Sharon that Bush has one desire: to avoid repeating his predecessor’s mistakes in the Middle East. A deep, Clinton-style involvement could mar the Bush presidency. According to this assessment, the Bush administration has no real plan to change the situation: His plan buys him time and avoids a confrontation with Sharon as well as domestic political fallout.

What it leaves Israelis and Palestinians with is a bitter standoff that could go on for years, as the Israeli military fills the security vacuum left by Arafat’s Palestinian Authority.

Saying that “a stable, peaceful Palestinian state” was essential for Israel’s long-term security, Bush did call on Israel to end its occupation of Palestinian territories, but by stating that Israel’s actions were dependent on “progress toward security,” he placed the onus firmly on the Palestinians; nothing concrete was demanded of the Israelis. This was music to Sharon’s ears. In Washington the Israeli leader told administration officials and members of Congress that in 10 years he hopes to see two states, Israeli and Palestinian, living in peace. The question has always been how to get there, however, and Bush has now given Sharon a completely free hand to pursue his military approach. In the short term, Bush’s speech gave tacit American consent to Operation Determined Way, Israel’s new offensive aimed at retaking the main Palestinian cities of the West Bank.

Last Friday, following another string of deadly suicide attacks, the Israeli cabinet decided to enter the Palestinian cities “for as long as necessary.” The military and security chiefs supported such action, claiming that laying siege to the occupied territories alone could not stop the suicide bombers, who hide in the cities and produce bombs there. Indeed, since the new invasion, there have been no suicide attacks in Israel. While the military was ordered to keep the Palestinian civilian authorities in place and avoid a full occupation, the new operation — with its open-ended timetable — indicates that Sharon wants to win the war by reoccupying the West Bank and crushing Arafat’s Palestinian Authority for good.

During his 16 months in office, Sharon has gradually built domestic and, more important, American support for such a decisive move against Arafat. Initially he might have settled for less. But as he and Arafat failed to reach even rudimentary agreements and the conflict grew bloodier, Washington gradually got used to ever deeper Israeli invasions into autonomous Palestinian areas. As the terror attacks continued, Arafat lost whatever threadbare support he had in either the Bush or the Sharon administration. The Labor party, partners with Sharon’s Likud in the coalition government, joined the cabinet consensus and supported the prime minister’s tough proposals. Sharon used the threat of expelling Arafat as a bargaining chip with Labor leaders, who supported the West Bank reoccupation and the expulsion of second-tier Palestinian leaders so long as Sharon agreed not to expel Arafat from his besieged Ramallah headquarters.

Sharon was very worried before Bush’s speech. As reported in Salon, he made a point of being the last person to catch the president’s ear, making trips to the White House on May 7 and June 10 and sending emissaries and intelligence officers in the interim to press the Israeli point of view on Bush. Last week Israel was rocked by a suicide bombing on a Jerusalem bus, killing 19 people. The Bush speech was scheduled for the next day, and the air was full of leaks about its contents, including timelines for a two-stage process, first a “provisional Palestinian state” without final borders, and then final-status agreement to end the conflict — plans that Sharon opposed. Sharon made a shrewd P.R. move: For the first time during the current war, he came to the bombing site, had his photo taken near the body bags, and said, “What kind of Palestinian state are they talking about?” The White House got the message and promptly delayed the address.

Given this reprieve, Sharon had a rare opportunity to push for last-minute changes in the speech. He wasted no time. The next day, the Israeli military intelligence attaché in Washington, Col. Shlomo Mofaz, came to the White House to meet Condoleezza Rice, Bush’s national security advisor, who had turned her office into the clearinghouse for the Middle East blame game. Mofaz gave Rice “the smoking gun”: documentary evidence showing that Arafat had funded the terrorist group al-Aqsa Brigades, even as he was publicly condemning the attacks.

Administration sources later told the New York Times that this new information was the final straw that led the president to call for Arafat’s ouster. But the Israelis did not have to work too hard to bring Bush around. The White House was already convinced that Arafat was worthless as a possible peace partner. Rice said publicly 10 days ago that the current P.A. could not be the basis for a Palestinian state. Administration hawks, led by Vice President Dick Cheney and Pentagon chiefs, had been pushing Bush to cut Arafat loose and avoid direct American intervention in the conflict. They were reinforced by both Democratic and Republican leaders in the Senate and the House, who voiced a strong pro-Sharon, anti-Arafat stance. The State Department, which favored a more balanced, active approach, remained isolated.

Bush’s speech went through 24 drafts, with the final version prepared on Monday morning. Ron Schlicker, the American consul general in Jerusalem and envoy to the P.A., said privately that after draft 14 or 15, Washington stopped sending his office further ones and did not ask for his advice on the contents. Schlicker was devastated by the speech, which undermined his credibility with the Palestinians. American diplomats in Tel Aviv shared this disappointment, as did Israeli foreign minister Shimon Peres, whose efforts to renew his talks with Palestinian leaders suffered a major blow.

“The Americans are convinced that Arafat is no partner for a sincere political dialogue,” a senior Israeli government official said before the Bush speech. “They believe that in order to move forward, we need a formula to sideline Arafat. The Egyptians, Jordanians, Saudis and many Palestinians share this view. But so far, no one has stepped forward to replace Arafat. In the meantime we face a governmental vacuum in the P.A. Arafat doesn’t behave like a head of government. His proposed reforms are not serious. So everybody’s waiting for Godot.”

The consensus within the Israeli security and intelligence establishment is that Arafat’s aim is Israel’s destruction and that he would never abide by any agreement, let alone fight his own people to stop their terrorist acts against Israelis. Arafat was considerably weakened in Palestinian eyes by his failure to fight against the vastly superior Israeli forces and defend his autonomy. But since there are no contenders for the Palestinian leadership, this standoff could go on for a long time, even years, while the Israeli army fills the security vacuum. It remains unclear how the Palestinians would conduct their promised elections in early 2003.

Gen. Amos Gilead, the head of Israel’s office of “coordination of the government’s operations in the territories,” is charged with assisting the Palestinian population. His main effort is to avoid restoring the Israeli military administration in the West Bank, and to work with the skeleton of the P.A. to provide basic services like health, education, water and food supplies. Gilead, a former senior intelligence officer, warned his superiors that taking full responsibility for the Palestinian population would cost the Israeli treasury $600-$800 million a year, a huge sum in a depressed economy. But as long as there are Palestinian officials to sign the receipts, international assistance will keep flowing into the territories. Therefore, Israel’s goal is to ruin the Palestinian Authority on the one hand, and at the same time to keep it just alive enough to keep foreign money flowing in.

Operation Determined Way aroused little media attention compared with that given Israel’s previous offensive, Operation Defensive Shield in April. This week, Bush refrained from calling on Israel to end its offensive. In his previous Mideast speech, on April 4, he demanded immediate withdrawal — a demand Sharon ignored and Bush never repeated. The administration’s sole cautionary note has been the statement that Israel should consider the consequences of its actions — an admonition that, coupled with the usual statement that Israel has the right to defend itself, is essentially meaningless.

His reluctance to step in between the Israelis and Palestinians notwithstanding, Bush has one major headache in the Middle East, namely, his fear for the Saudi regime’s survival. Israeli intelligence has told Sharon that a Saudi collapse is Washington’s nightmare. The kingdom holds the world’s largest oil reserves and suffers from social and political unrest, amplified by the bad news from Palestine. Given this threat, Bush wanted to “park” the Israeli-Palestinian issue in order to focus his attention on more important problems.

In recent months, the Saudis have signaled their growing distress to Washington and even tried to engage Sharon. A senior Saudi official met secretly with an Israeli official in March to explain his kingdom’s peace initiative and bring a message from Crown Prince Abdullah. According to a well-placed Israeli source, the Saudi said: “Don’t think that we came up with our plan to help our P.R. effort in America. We face a dangerous domestic situation, with 50 percent unemployment and sharp decline of the per capita GNP.” The message was clear: Calming the Israeli-Palestinian bonfire was crucial to Saudi well-being. Similar signals came from Cairo and Amman, the pioneers of peace in the Arab world.

Sharon evidently concluded that the moderate Arab regimes were weak and were crying for America’s help without having any real clout in Washington. But nevertheless, true to his suspicious nature, Sharon feared a Saudi-American deal to save Arafat at Israel’s expense, especially after Bush called upon Arab leaders to play a greater role in curbing the fight.

In Israeli eyes, even the most moderate Arabs do not accept Israel’s right to exist in the midst of the Arab world. The regimes in Cairo, Amman and Riyadh have a strategic interest in making peace with Israel, but their people are educated to hate Israel and pray for its destruction. As for their ruler, they play a delicate game: They talk with Sharon in private and censure him in public.

In visits with Bush, Saudi and Egyptian leaders told him to restrain Sharon and come up with a new American initiative. But Sharon had two advantages over them: They could not deliver the Palestinians or pledge to stop the suicide attacks, and therefore their plans were purely theoretical. Moreover, both were competing for Arab prominence, which gave Sharon the leverage to play them against each other. The Saudis demanded a Bush statement on Israel’s withdrawal to 1967 lines. The Egyptians preferred a timetable for final-status agreement. Sharon opposed both ideas fiercely and got his way with Bush, who ignored the Arab pleas.

“Sharon’s last visit made the difference,” one of the prime minister’s aides told me. “He had a very good meeting and lunch with the president. Eventually, every Sharon idea turns into reality [with Bush], even if it takes time.” Sharon proposed to replace Arafat with an interim government, Afghanistan style, headed by a new “chief executive” with international support and supervision. This new regime would prepare for a general election after a year. Bush did not subscribe to the idea, “but we might need to return to that model,” said the Sharon aide.

On the morning after, the administration tried to calm its Arab and European allies and Bush flew to Canada, where he would try to forge a Middle East consensus with his G8 partners. The E.U. wants Bush to convene the long-touted regional peace conference, which wasn’t mentioned in the speech at all. “The Bush proposal for Palestinian democracy is great, especially since American legal experts prepared the Saudi democratic constitution,” an angry European diplomat said sarcastically in a meeting with Peres on Wednesday. (Saudi Arabia is a notoriously undemocratic autocracy.)

The coming weeks will see resumed diplomatic efforts focusing on the regional conference and preparing Palestinian elections. But on the ground, the new Israeli occupation is taking hold without a clear end in sight.