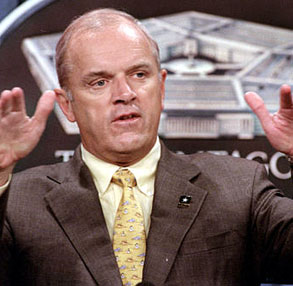

For seven months now, Democrats on Capitol Hill have been trying to find out what, if anything, Secretary of the Army Thomas White knew about Enron’s suspect accounting practices while he was vice chairman of that company’s retail unit. Specifically, they want to know if he was aware that Enron used manipulative trading tactics to take advantage of California’s electricity market.

We may find out Thursday, when White — the highest-ranked administration official to do so — will testify about his role with Enron.

Or will he?

In a Newsweek report released Sunday, Republican sources are cited as saying that they wish White would resign rather than testify and also that White will invoke the Fifth Amendment and not answer questions if he does appear before the Senate Commerce Committee. That prompted Rep. Billy Tauzin, R-La., who heads the House Energy and Commerce Committee, to suggest that White might deserve a pink slip. “If you’re going to do that, maybe you ought to find another job,” Tauzin said on ABC’s “This Week.”

But on Monday, Pentagon spokesman Maj. Mike Halbig told Salon that White would testify and would not take the Fifth. Later, in a statement to the Associated Press, White said that not only would he testify, but also that he had no intention of resigning his post.

If he does testify, White will face some senators who appear to have made up their mind about him. The Army secretary has become a regular whipping boy for Democrats since last fall, when his job at Enron was first spotlighted. There was White’s failure to sell off his $12 million in Enron stock until October, five months after he took his job with the Bush administration. There was his statement to a congressional committee that he had had 29 contacts with his former colleagues at Enron, when that number proved to be 84. And, most controversial, there was his role as vice chairman of Enron Energy Services, the scandal-plagued unit responsible for providing electricity services to large and small businesses.

White rose to head the division during 11 years at Enron. But Energy Services has been accused of using bookkeeping sleight-of-hand to turn multimillion-dollar losses into multimillion-dollar profits. For example, Enron whistleblower Sherron Watkins told Congress that White’s retail division shifted losses totaling a half-billion dollars to his wholesale division, allowing retail to show a $105 million profit. But with his bonuses tied to performance, White raked in more than $30 million last year.

White’s performance before the committee will be made even more difficult by its timing. According to a Senate source, a morning hearing will precede White’s testimony and focus on corporate responsibility. It will include testimony from former Sen. Howard Metzenbaum (now with Consumer Federation of America), and Joan Claybrook, director of corporate watchdog Public Citizen, a dogged White critic.

Stacked deck or not, some members of Congress already have firm beliefs about White. According to sources close to Sen. Barbara Boxer, D-Calif., and Rep. Henry Waxman, D-Calif., both have concluded from interviews with former Enron employees that White is unfit to be secretary of the Army.

“Either Secretary White was an out-to-lunch executive while he was vice chairman of Enron or he knew about the company’s high jinks,” said a deputy counsel to one key Democratic lawmaker. “Either way, based on those two scenarios, he’s screwed. He’s certainly not fit to be secretary of the Army.”

White has maintained that while he was at Enron he was unaware of any of the company’s shady business practices.

But aides to Waxman and Boxer told Salon that they have spent the past month phoning more than two dozen former executives and salespeople of Enron Energy Services.

The questions posed to the former Enron employees: Was Thomas White familiar with Enron’s accounting practices? Did he take part in meetings where the company’s accounting practices were discussed? Did Thomas White ever tell you to use mark-to-market accounting when showing profits? What were White’s and EES’s roles in the gaming of the California electricity market?

Some employees told investigators that White — whom everyone referred to as “the general” — was unaware of Enron’s off-the-books partnerships and manipulative trading tactics. And other former colleagues contacted by Salon agreed.

“I know everyone would like to implicate him, but he didn’t know anything,” says Margaret Ceconi, a former finance executive at EES. Ceconi had written a letter to ex-Enron chairman Ken Lay last August, raising concerns about EES, saying it was hemorrhaging cash despite showing strong earnings.

But Steve Barth, an EES vice president who left the company last July, said White was fully aware of EES’s accounting practices and knew full well that the unit played a part in California’s energy crisis. White “was there every step of the way,” Barth told Salon. Barth left EES and went to Enron’s broadband unit in 1999 before leaving the firm last July. He has spoken with investigators for the Senate committee.

The energy crisis that rocked California in 2000 and 2001, with its unprecedented power prices and rolling blackouts, played a key role in the rise and fall of the Enron Energy Services division, former executives said. Some former EES executives said skyrocketing power prices enabled the division to sign contracts with large businesses whose owners feared they would be hit with expensive electricity bills — or would lose millions in blackouts. The crisis in California also helped the retail unit sign contracts with large businesses in other states because business executives feared deregulation of their electricity markets would result in a California-like crisis.

During the height of the crisis, EES signed more than $1 billion in long-term energy deals with companies such as Compaq Computer, Starwood Hotels & Resorts, Rich Products, and Prudential Insurance of America, all of which have operations in California.

Moreover, the December 2000 Enron memos, which detailed how the company’s traders tried to boost wholesale electricity prices and exploit loopholes in California’s electricity market, described the integral role played by EES. The Enron attorneys who wrote the memos outlined an example of a practice whereby Enron would schedule 1,000 megawatts of electricity for delivery to EES. But the unit would take only 500 megawatts, generating a bonus for Enron for the remaining electricity that California’s grid operator would pay under the market rules.

Enron also facilitated the strategy for other companies using a “dummied-up” load from EES, the memos say.

White told reporters shortly after the memos were made public in May that he had no knowledge of the trading tactics.

“We were a customer of the wholesale group. We were not privy to their strategies,” he told the Washington Post. If power buyers at his unit were involved, “I was not aware of it,” he said.

Still, several former energy services executives told Salon that White’s primary role, as “cheerleader,” was to cultivate new business for EES and help Enron sign contracts with the military.

Either way, White appears to be in a tough position: Did he know about EES’s shady practices? If not, why not? While taking the Fifth might mean political suicide, his options Thursday don’t remain substantially more attractive. The Washington Monthly recently argued that if “White [had] made his missteps in any previous administration, he most certainly wouldn’t have lasted.” His performance Thursday will surely determine if he’ll continue to.