In the scheme of James Bond movies, Maurice Binder is the fifth Beatle. Just as there are several people associated with the Fab Four competing for that honorific (George Martin, Brian Epstein, Stu Sutcliffe, Pete Best), there’s more than one person involved with the 007 series whose contributions to the spirit and success of the movies make them invaluable.

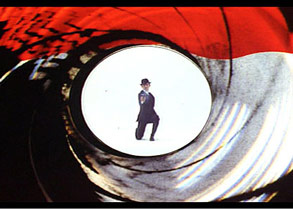

John Barry composed the sumptuous scores for most of the great Bond films; Monty Norman wrote the distinctive rumbling Bond theme; production designer Ken Adam conceived most of the cavernous villains’ lairs in which Bond finally meets each episode’s arch-nemesis. (Ian Fleming, who of course deserves credit for creating Bond in embryo, would not be in the running. It’s shocking how much the movies improved on Fleming’s flat, pedantic writing, transforming Bond from a puritan disgusted by sex and violence to a suave libertine sadist getting his kicks from them.) But for me the most invaluable Bond Beatle is Maurice Binder, who designed the title sequence for the first Bond film, 1962’s “Dr. No.” He went on to design (after leaving the credits for “From Russia With Love” and “Goldfinger” to Robert Brownjohn) for every Bond film from 1965’s “Thunderball” to 1989’s “License to Kill,” 14 in all.

The best source of information on Binder is in a short documentary included on the DVD for “On Her Majesty’s Secret Service” (and let’s take a moment to salute MGM/UA for the loving care with which it’s packaged the films on DVD). Binder was born in New York in 1925: In his youth he was an art student and later he became the head of advertising for Macy’s before eventually going into movies. He was an art collector, a lover of women, a lifelong bachelor. He died of lung cancer in 1991. The details are sketchy. What all the friends and colleagues interviewed for that documentary agree on was that Binder was a charmer and also a very private man. One friend describes going to his funeral, seeing many people she knew, but having no idea that they too were friends of Binder’s.

What we can deduce from Binder’s title sequences is that his sensibility was a perfect match for Bond’s. They are the work of a sensualist connoisseur who went about his work with a naughty sense of play. It’s amazing how many nude women Binder was able to work into PG and PG-13 films by shooting them in silhouette or keeping their naughty bits tantalizingly obscured by the credit titles. That visual striptease is an equivalent of the double entendres that stud Bond’s witticisms (and given such character names as Pussy Galore and Holly Goodhead, Binder’s work is often a lot subtler).

I think that to appreciate the flavor of Binder’s work we first have to acknowledge that there were always two 1960s. There was the decade summed up by a National Lampoon bit as “the protests, the marches and, most of all, the music,” and there was the pop ’60s. Now, when the entire culture seems to be nothing but pop, when deconstruction and iconic tomb-raiding and ironic self-consciousness is the order of the day, when oldies have replaced Muzak in the supermarket, when it’s no big deal to see comic books made into movies, when the culture seems nothing but pop, it may be hard to remember the kick of having fashion and pop music and graphic design invade the sensibility of mainstream entertainment.

The most incongruous moment in any Bond movie occurs in “Goldfinger,” when Sean Connery complains that drinking Dom Perignon unchilled is like “lish-ning to the Beatlesh without earr-muffsh.” That line would seem to draw a barrier between the two ’60s, between teenagers and their parents, between hipsters and swingers, between Yeah! Yeah! Yeah! and dooby-dooby-doo, between the Evergreen Review and Playboy, between the pot smokers and the martini drinkers. But the line doesn’t work, because Bond movies inhabit the same pop universe as the Beatles.

I understand why veterans of the decade’s political struggles or the decade’s military veterans may recoil from reducing the ’60s to pop. But to many of us too young to have participated politically in the era, or people who weren’t even born then, the freedom of the ’60s was experienced primarily as the pop explosion. My knowledge of Vietnam and the Civil Rights movement, of Bob Dylan and “The Armies of the Night,” came later. The ’60s, as I experienced them, were “Batman” — In Color, Petula Clark, “Shindig,” the flip hairdos my female cousins wore, “King of the Road,” Ed Sullivan, “The Avengers,” the Mattel line of secret agent toys and, above all, the Beatles.

I was too young to enjoy the Bond movies in the way that adults enjoyed them, as escapist fantasies of luxury and adventure and sex and travel. The pleasure that the Bond films continue to give me (and, I’d venture, my contemporaries) is partly the distinctive pleasure of finding out that something you responded to as a kid stands the test of time, giving you adult pleasure even as it recalls the thrill it originally gave you.

At its most basic, Binder’s work was proof that squares could get a kick out of psychedelia, too. His title designs — swirling neon fogs of color set against enveloping backgrounds of velvety black — are all about freedom, not only the freedom of a filmmaker to work abstractly instead of narratively, but a metaphor for the sexy and liberating physical exhilaration of watching James Bond’s adventures. You could say that Binder was to Isaac Newton what Blofeld was to Bond. His title sequences are three-minute refutations of the laws of gravity: Figures jump and bounce and run through the colorful voids, or simply luxuriate in midair as if the atmosphere itself had become the most inviting bed in the universe. The sequences are a distillation of the films to color and movement and sex.

For all that, and for all the bombast of the movie’s theme songs (taken together, a battle of the bands where Shirley Bassey goes head to head with Paul McCartney and Wings, where Nancy Sinatra purrs and Tom Jones wakes the dead), Binder’s title sequences are strikingly becalmed. They move with a deliberate and luxuriant sensuality, drinking in all the nudie cuties prancing and posing through them. It’s pure sex, both hot and cool, urgent and deliciously slow, celebrating both pursuit and release. The sequences are so rich, the atmosphere so thick, you begin to feel as if you could walk up the aisle into the screen.

In “You Only Live Twice” (which features the most beautiful of the series’ theme songs, Nancy Sinatra’s one indisputable moment of glory) a solarized background of an erupting volcano gives forth the skeletal outlines of Japanese parasols that burst from the hot lava like fireworks, or emerge from the eyes of geisha beauties. The voluptuous black women in “Live and Let Die” (the crudest film in the series, with its voodoo baddies encompassing two overlapping stereotypes: blaxploitation badasses and the restless natives of Tarzan movies) are what every teenage boy of a certain era hoped to find in National Geographic. In “For Your Eyes Only” (featuring a wet, red close-up of what Binder called Sheena Easton’s “70-millimeter lips”) a naked (natch) girl runs through a background of color provided by a looming close-up of a fiber optic lamp. In “On Her Majesty’s Secret Service,” a phalanx of naked girls surround a Union Jack as if they had become the lions of Britannic crests.

That picture (along with “You Only Live Twice,” the best film in the series) features one of Binder’s most ingenious sequences. Binder had to prepare the audience for a new Bond (George Lazenby, who acquits himself much better than he’s generally given credit for). His solution was to use images from the previous five films pouring like sand through a martini-shaped hourglass while, on the other side of the screen, a Bond figure dangles like Harold Lloyd from the hands of a clock running backward. In many ways, “OHMSS” finishes off the Bond saga that began with “Dr. No” (it’s also the only openly emotional Bond film), and in retrospect the hourglass is a prescient image, a hint that, for Bond, time was running out.

With a few exceptions the Bond series has never again been the consistent delight it was in the ’60s. Pierce Brosnan, fine in “The Thomas Crown Affair” and absolutely first-rate in “The Tailor of Panama,” has never gotten the swing of the character, which, while Clive Owen and Rupert Everett are around, seems a waste of time. (And hasn’t anyone taken notice of lovelies like Drew Barrymore, Charisma Carpenter and Kylie Minogue for Bond girls?) The director’s chair has been occupied by a revolving series of hacks. And the movies themselves have been reconceived as run-of-the-mill action movies instead of continuing to be swanky daydreams of sex and violence.

It’s a sad, sputtering state of affairs for the longest continuously running movie series and one that holds a special place in the affections of moviegoers. It’s somehow tragically fitting that the last Bond film Binder worked on before his death from lung cancer was also the last to show 007 smoking, and even featured the surgeon general’s warning in the end credits. (My God! What next? Bond stopping to slip on a condom, or giving up martinis and switching to a low-fat diet?)

It’s amazing that given the declining quality of the series — the last few Roger Moore entries (“For Your Eyes Only” and the absolute nadir of the series “A View to a Kill”) and the gray, indifferent blur of the two Timothy Dalton entries — Binder’s work continued to be first-rate. His masterpiece came in 1977 with his work on “The Spy Who Loved Me,” not just the best of the Moore Bonds but one of the best entries in the series, an example of the wit and grace and sprightliness of craft that can exist in big-budget filmmaking. Binder was always alive to the erotic potential of hands. The girls in his title sequences are always beckoning like belly dancers, as if they were conjuring the fantastic images and vivid colors from their fingertips.

The opening sequence of “The Spy Who Loved Me” ends with Bond ski jumping off a mountain slope. The music cuts out and we see his figure falling through the air and kicking off his skis, before finally opening a parachute that blooms into a Union Jack. A silhouette of a woman’s hands rises from the bottom of the screen to cradle the parachute as the first tinkling of “Nobody Does It Better” (the wittiest of Bond theme songs) begins. What follows is a sly joke on the phallic imagery of Bond films.

A huge gun barrel appears on the left side of the screen, which serves as balance beam and parallel bars for naked women to cartwheel along or swing from. A cutout of Moore is encircled by bejeweled hands, each holding a gun, until Bond has turned into a many-armed Indian icon. Images of Bond and some young lovely running are repeated and laid over each other in a slow-motion reverie of perpetual action. A slight push from Bond’s finger topples a line of rifle-bearing beauties in Cossack hats. The mellifluous flow of Binder’s work was never as erotic or as funny as it is here. He seems to be playing a relaxed game of “Can you top this?” — daring himself to come up with more inventively racy images and effortlessly pulling them off. It’s the work of a peerlessly worldly conjurer.

The particular mix of sex, adventure and luxury of the Bond movies has never been matched. It says something about the essentially disreputable appeal of movies that the Bond series, the most sophisticated disreputable films ever made, can seriously be spoken of as beloved. And not just the movies but the people who took part in them: So many of those people have left us. In addition to Binder there is Bernard Lee who played M, and most recently Desmond Llewelyn as Q, who made perpetual irritability seem like a state of comic grace. (Lois Maxwell, who played the Miss Moneypenny, before being fired from the series, is, thankfully, still with us.) It would be enough for anyone in the movies to earn an audience’s pleasure. It says something about the work Binder and his colleagues have left behind that it has earned our love.

This story has been corrected since it was first published.