One thing that heroes and villains share, it seems, besides the likelihood of an early death, is the probability that the first version of their stories will be hack work. Not that the writers behind the two newest Sept. 11 books, "The Cell" and "Among the Heroes," aren't fine journalists when on their regular beats, but they're primarily reporters, not authors. (Some wondrous writers are both; these aren't.) We turn to books rather than newspapers when we want more than the facts about a historical event. In books, we seek a wider and deeper context for those facts, not just who met with whom and where and when and what they did, but why they did it and what it all means.

Even the very best of the daily press suffers from this focus on trees at the expense of forest. The special section the New York Times produced in the months after Sept. 11, A Nation Challenged, is a case in point. It won a Pulitzer Prize, and it certainly devoted more inches to covering the attacks and their aftermath than any other newspaper, but much of the time the information in it rattled around randomly like loose nails in a tin can -- endless columns of undigested information that left many who read them feeling more confused and ignorant than before. Perhaps that's why so many Americans, even those who managed to wade through long stories on the ongoing skirmishes in Afghanistan, don't fully realize how perilous the situation there is. On the other hand, readers of Ahmed Rashid's excellent book, "Taliban" (which was written before Sept. 11 but which still provided a better overview of Afghanistan's political dynamics), will perceive that the nation (particularly outside Kabul) is slipping back into exactly the same violent chaos that caused so many exhausted Afghans to accept the Taliban regime to begin with. When journalist-authors such as Michael Ignatieff deliver stories like his invaluable report from Afghanistan in the July 28 issue of the New York Times Magazine, we get the best of both worlds: recent developments and the background we need to make sense of them.

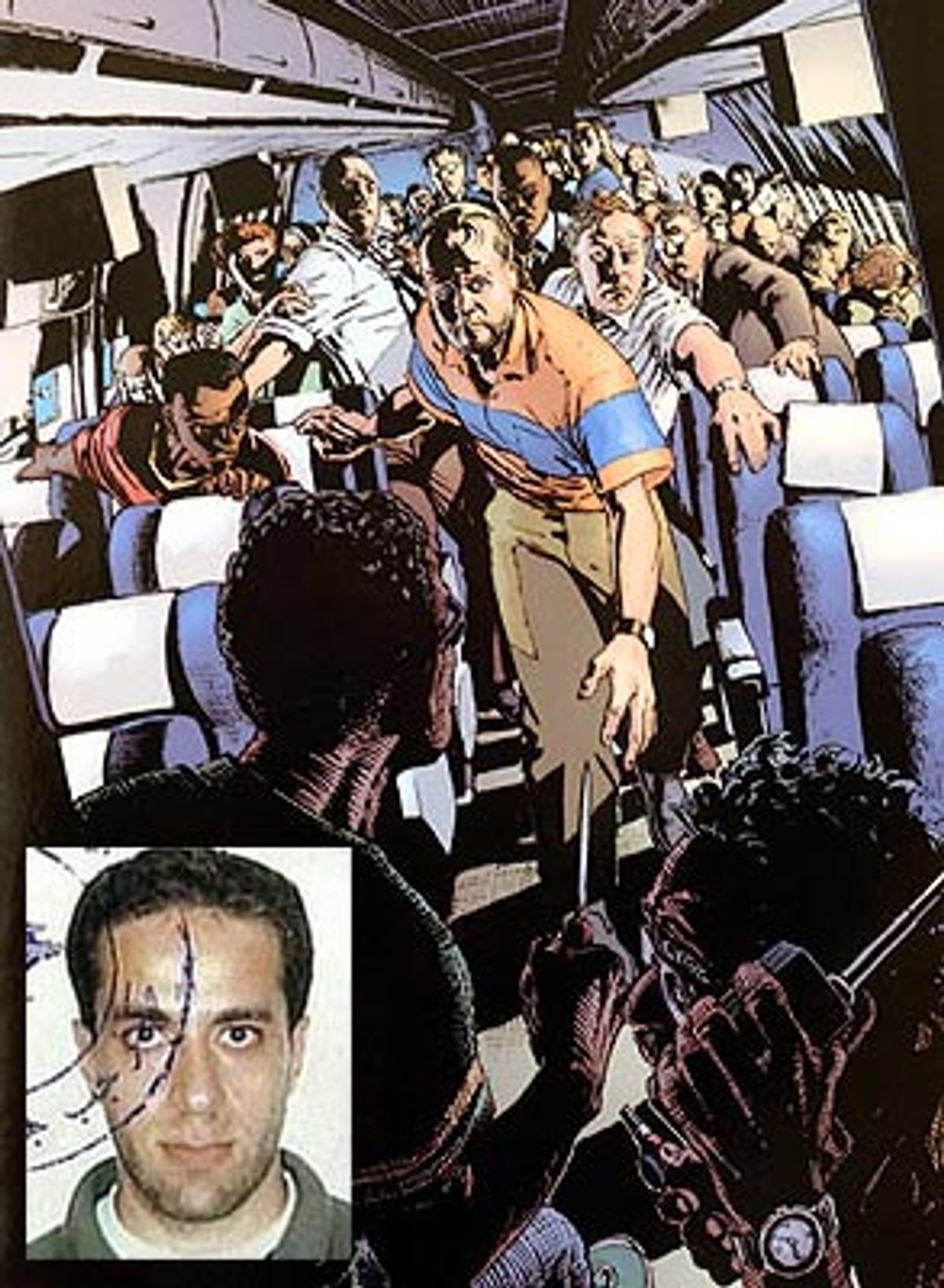

Both "The Cell" and "Among the Heroes" promise to provide readers with definitive accounts of what we now know about two aspects of the Sept. 11 story. "The Cell" -- written by John Miller (of ABC's "20/20"), New York crime reporter Michael Stone and journalist Chris Mitchell -- traces the activities of the cell of hijackers responsible for crashing the four airliners. "Among the Heroes," by New York Times reporter Jere Longman, recreates the trajectory of United Airlines Flight 93, from its beginning as an ordinary nonstop to San Francisco from Newark International Airport to its hideous end as a smoking crater in a field outside Shanksville, Pa.

Both books are presented by their publishers as if they contain revelations -- "Among the Heroes" was embargoed to the press until its publication date last week, apparently because Longman persuaded several family members who were permitted to listen to the cockpit recorder tape to debrief him. It's not clear that anything in either book constitutes a significant news flash, unless you're one of those people whose strategy for coping with major catastrophes is to spin out conspiracy theories. If you are, be advised that Longman persuasively dispatches the "it was shot down" theory on Flight 93.

The hot story touted in "The Cell" involves El Sayyid Nosair, an Egyptian who ostensibly shot and killed Rabbi Meir Kahane of the extremist Jewish Defense League in Manhattan in 1990 (he was convicted only of a weapons charge, but no one seems to much doubt his guilt). The authors demonstrate that Nosair had close ties with several Middle Eastern men who hung around the al-Kifah Refugee Services Center in Brooklyn, a recruiting outpost for mujahedin hankering to fight the Soviets in Afghanistan. Osama bin Laden's mentor and al-Kifah's founder, Abdullah Azzam, made several fund-raising visits to the center during the 1980s and it was frequented by Sheikh Omar Abdel-Rahman (known to newscasters everywhere as "the blind Egyptian cleric"), as well. Nosair's pals would eventually go on to participate in the 1993 bombing of the World Trade Center with the blessing of Abdel-Rahman and under the direction of Ramsi Yousef.

Whether this is a big deal or not is a matter of opinion. Even judging by the events as described in "The Cell," Nosair's shooting of Kahane seems to have been a largely impulsive act (though he'd talked big about it among his buddies beforehand) triggered in part by his frustration over a job transfer. The alleged co-conspirator who was with Nosair at the time had wandered off to the men's room and didn't seem to know what was going on until after the shooting; the "getaway car," a taxi driven by another of the al-Kifah crowd, wasn't anywhere in sight while Nosair attempted to flee the scene and he had to commandeer another one instead. In short, these guys sure look like a pack of jokers, even if Nosair, the head joker, managed to overcome his general ineffectuality long enough to kill somebody. It wasn't until Ramsi Yousef -- an evil genius if there ever was one -- showed up in 1992 and whipped Nosair's pals into shape long enough to execute the first attack on the Trade Center that they became genuine terrorists. Yousef got out of Dodge the day of the bombing, leaving the jokers -- including one who tried to get a refund on the security deposit for the rental truck they'd used as a bomb -- to be scooped up by the cops.

Most of the significant facts about Nosair that are reported in "The Cell" also appeared in Peter Bergen's "Holy War, Inc.: Inside the Secret World of Osama bin Laden," a book published in November 2001. There's also been some fuss over 16 boxes of documents seized from Nosair's home when he was arrested after the Kahane assassination; they included training manuals from the Army Special Warfare School at Fort Bragg and some communiqués addressed to the secretary of the Army and the Joint Chiefs of Staff, as well as maps of New York City landmarks.

As Bergen also reported, this material was given to Nosair by a remarkable character named Ali Mohamed, who had the distinction of being a member of al-Qaida, a soldier in the U.S. Army and an instructor of U.S. Army Special Forces at the same time. Mohamed even popped over to fight a bit of jihad in Afghanistan when he got time off from paratrooper training at Fort Bragg. Shocking, isn't it? Well, no, not really. This was during the '80s, when the U.S. and the mujahedin were on the same side: against the Soviets.

Again, all of this is in Bergen's book, though "The Cell" does contain more details about the bureaucratic limbo that the 16 boxes fell into when the FBI gave them to the Manhattan D.A. and the D.A. forgot to tell the NYPD that the FBI had released the material and so it never got read, let alone translated, until after the 1993 Trade Center bombing. A major vein in "The Cell" concerns all the ways that various government entities -- usually the FBI and the CIA -- screwed up in investigating Islamist militants in the U.S. and overseas. Most of the authors' sources are detectives and special agents, line staff who understandably and perhaps justifiably would like to see higher-ups -- overly cautious managers and meddling politicians -- blamed for the failures. But it's clear that venomous turf wars between the FBI and the CIA, the FBI and the NYPD, various divisions within the NYPD itself, and New York's Joint Terrorism Task Force (an NYPD and FBI collaboration) and everyone else are equally if not more culpable. Serious structural reform is in order, to say the least.

What does all this stuff about the Kahane shooting really have to do with Sept. 11, anyway? It's hard to say, which is why "The Cell" itself could do with a little structural reform. The book is a mess, with no index, no footnotes and a propensity for slipping into first-person passages -- very confusing in a book with three authors -- that you eventually realize relate John Miller's own experiences in covering the events. Mostly these passages (sometimes set in type smaller than the rest of the book's text, and sometimes not) consist of Breslin-esque yarns about the "colorful" New York law enforcement characters he befriended in various "watering holes," alternating with starry-eyed vignettes of his life as a TV personality. (Variations on the phrase "as I sat next to Peter Jennings at the ABC News desk" appear no fewer than four times in the first 30 pages.) Miller has been covering terrorism for years, and he did interview bin Laden in 1998, so surely some of the actual reporting in "The Cell" comes from his notepad, but these preening interludes only foster the impression that he contributed little of substance to the project beyond a famous name to put on the book's cover.

Most of "The Cell" is padding, workmanly retellings of the highlights of al-Qaida-related terrorist actions over the past decade -- Riyadh, the African embassies, the U.S.S. Cole, etc. -- grisly greatest hits that have been covered in other books. However, its reconstruction of the Sept. 11 cell's history and movements is new and valuable, even if it's a bit sketchy and it doesn't amount to much more than a quarter of the entire book.

The only hijackers about whom the authors have much information are Mohammed Atta and Ziad Jarrah, the man who led the team that commandeered United Flight 93. Much of this has been reported in news outlets, but it's helpful to have it compiled in one place, particularly because Atta, a complex personality, may embody the psychological prototype of a "new" breed of terrorist. As Gilles Kepel has pointed out in his excellent "Jihad: The Trail of Political Islam," the majority of the most vehement militant Islamists don't conform to the American stereotype of disenfranchised, downtrodden Palestinian youths pushed past the brink. Atta, like Yousef and several of the other leaders of the Sept. 11 attack as well as many of Islamism's most fervent champions in the Mideast, had an engineering degree and came from a family of comfortable means. (Many of these men, like Atta, faced difficulty finding work commensurate with their education, though.) The story of Atta's fraught relationship with his prosperous, egotistical father, who derided him as a mama's boy, is intriguing, but the authors of "The Cell" don't do much with it.

Jarrah, however, is truly a baffler. While Atta became more puritanical and unpleasant to outsiders as he grew increasingly religious, Jarrah was invariably characterized by the Westerners who met him as "nice" -- a warm and jovial fellow who had a serious romantic relationship with a Turkish woman whom he lived with in Germany. He met her in a disco, reportedly drank alcohol, and was described by a fellow student as a "weak Muslim" who had to be dragged to prayers. He is not known to have uttered a word against America and sometimes seems to have liked it. Atta, by contrast, was thoroughly disgusted by the depravity and "chaos" of one Western film a roommate persuaded him to see: Walt Disney's "Jungle Book."

The radicalization of Ziad Jarrah is just one of the mysteries of Sept. 11 that remain mostly unilluminated by these two books. Longman, who has to set his portrait of Jarrah against his depictions of some of the 40 crew members and passengers on Flight 93, seems particularly wobbly when it comes to the task. "Among the Heroes" is, in bulk, a compendium of tributes to the Americans who died in the plane crash; the format of those tributes conforms to that of the New York Times' "Portraits in Grief" feature in A Nation Challenged (pieces later compiled into a book).

Responses to "Portraits in Grief" vary a lot -- some people are tremendously moved by them, but to my mind they start to feel pretty formulaic by the time you've read a dozen or so. Writing them must be an unenviable task; they mostly serve the needs of the deceased's loved ones, and like most postmortem testimonials they're heavy on the praise and light on the deprecation. Any abrasive qualities the individual possessed come enrobed in a thick coating of retrospective fondness; profligacy becomes generosity; tyranny becomes "demanding the best," and so on. The problem is, our faults are often the most interesting and revealing things about us, so in satisfying the need of survivors to lionize their dead, the "Portraits in Grief" often seem generic, like the self-descriptons in personals ads.

Longman tries to gin up some interest in these stretches of the book by explaining that the passengers on Flight 93 "were not ordinary citizens placed in an extraordinary situation, as they have often been portrayed," but rather were "people who were at the top of their game." This means either that they were successful businessmen (not too surprising for passengers on a weekday flight, and almost inevitable in first class) or individuals with backgrounds that especially suited them to dealing with the crisis -- the flight attendant who had the ingenious idea of boiling water to throw on the hijackers, for example, was a former police detective. But in truth, these people do seem "ordinary" in the way that all of us (except perhaps celebrities) are -- full of hidden dimensions that remain stubbornly hidden. Then "Among the Heroes" indulges in the usual lingering over the kind of coincidences that must be torturing the passengers' loved ones -- the decision not to blow off that out-of-town conference, or the gratified impulse to hop on an earlier flight.

Most of the above feels like grist for water-cooler philosophizing about the nature of fate and, at worst, like sops to the victims' families to avoid charges of ghoulish opportunism. (Only one family member declined to participate.) What the average reader will seek here is a solid account of what happened in the minutes before Flight 93 hit the ground. This story -- the story of the passengers and crew who realized what the hijackers had in mind, put their heads together and decided to storm the cockpit -- is one of the few heartening tales to be extracted from the vast tragedy of Sept. 11. (The bravery of New York's firefighters is another.) While there is definitely something voyeuristic about wanting to know just what happened on that plane, our reasons are legitimate enough: We want to believe that in this case, once they knew the true score, Americans refused to be victims and fought back in the face of near-certain death. We want to tell ourselves that we would, too.

The problem is, there just isn't that much hard data about those final minutes. The cockpit tape-recorder produced a garbled, often unintelligible record of the events. Longman, like the authors of "The Cell," is nothing if not a conscientious reporter; if he can't substantiate something, he's not going to fudge it. So the climax of his story is little more than a series of questions -- we can't even be sure if the passengers succeeded in storming the cockpit, let alone if they got in and made a last-ditch attempt at pulling the plane out of its descent. Plus, even asking such questions as "Who did the storming?" (if such storming occurred -- investigators think the passengers might have used a food tray to batter the cockpit door) have become loaded. Some family members feel that it turns the tragedy into "an Olympic contest, where some passengers deserve gold and the others only silver and bronze."

Longman, to be fair, is hemmed in by both the lack of evidence and the delicate protocols of bereavement; maybe it's unfair to ask him to spin straw into gold. Still, you sometimes wonder if he could spin even gold into gold; there are sentences in "Among the Heroes" that are truly wince-inducing. He describes Jarrah's face as resembling "the pasty-murderer look that Lee Harvey Oswald had in his pursed lips of history altered," the passengers as "people who would not allow forced enormity" and President George W. Bush as sporting an impossible "look of stunned nonchalance on his face."

But even if we had all the facts about Sept. 11, if we knew who did what just before Flight 93 crashed, or how the other hijackers managed to overpower the crew and passengers on the other planes, there would still be questions. Some are specific to individuals -- What turned the cheery Ziad Jarrah into a mass murderer? for example -- while others are political -- Is the kind of terrorism we suffered on Sept. 11 avoidable, and does it have any grounding at all in legitimate grievances? Still others are existential -- Why do such terrible things happen to innocent people and how do we go on once we're forced to understand that they do and that all the homeland security in the world won't make life completely safe? These are some of the mysteries that only our best writers and thinkers can come close to plumbing. But if "The Cell" and "Among the Heroes" are any foretaste of the tidal wave of Sept. 11 books about to descend on us, we shouldn't expect them to do so anytime soon.

Shares