Has Clint Eastwood gotten better or have mainstream movies gotten so bad that it just seems as if he’s gotten better? Eastwood has always been a pedestrian, literal-minded director, with no particular imagination or visual flair. The actors who’ve worked with Eastwood have been talking for so long about what a pleasure it is to make movies with him, and about how assured and relaxed he is, that it’s got to be sincere instead of hype or professional courtesy.

The trouble is that that sense of offhand relaxation — the thing that makes, say, Howard Hawks’ movies one of Hollywood’s lasting joys — never seems to make it into Eastwood’s dogged, deliberate movies. (Though some of the interplay between Eastwood, James Garner, Tommy Lee Jones and Donald Sutherland in Eastwood’s last picture, “Space Cowboys,” came close.)

But Eastwood is competent, and if that sounds like damning him with faint praise, let me hasten to point out that competence, even the most basic competence of providing a plot that makes sense, is not something we can routinely expect from Hollywood anymore. Eastwood’s new film of Michael Connelly’s mystery novel “Blood Work” is a typically meat-and-potatoes piece of direction. And that has something to do with why it’s pleasing to sit through, how it manages to be involving without being in your face.

It’s not an important picture, and probably not even a memorable one, but I had a good time. It’s a relief to see a mainstream entertainment that doesn’t feel as if it’s aimed at a 14-year-old’s sensibility. And not just because there are no explosions or car chases and the gunplay is kept to a minimum. There’s something like discretion in Eastwood’s direction and in Brian Helgeland’s screenplay. This is a serial-killer thriller that doesn’t feel as if it was made by a closet necrophiliac. Eastwood doesn’t linger on the bodies at the crime scenes, and Helgeland has wisely eliminated an awful story from Connelly’s novel about the unsolved case that haunts the lead character. (It’s such a grisly tale that it makes you want to glue those pages of the book together.)

There are other liberties taken with the novel: The mystery has been streamlined and characters and subplots eliminated. But as a Connelly fan, I didn’t sense any disrespect for the source. Eastwood has made a detective movie that’s really about detection. Which means we watch him tracking down leads, putting the pieces of the case together, talking to people. It’s a good joke that the most reckless piece of physical daring in the entire movie comes when a man who’s had a heart transplant bites into a Krispy Kreme doughnut (those things’ll kill ya — and I could eat four right now).

That man is Terry McCaleb (Eastwood), an FBI profiler who had to retire from the job after suffering a massive heart attack while chasing a perp known as the Code Killer. Two years later, Terry and his newly installed ticker are leading a quiet life on his houseboat. A young woman named Graciela Rivers (Wanda De Jesús) approaches him and asks him to investigate the murder of her sister during a convenience-store robbery. Terry refuses, explaining that he’s off the job. Until Graciela tells him that it’s her sister’s heart he’s carrying around in his chest. Over the objections of his doctor (Anjelica Huston, who projects a nice, snappish air of authority), and the cops (Paul Rodriguez, allowed to act too grating and off-putting, and Dylan Walsh) who don’t want him interfering in their case, Terry begins to investigate the murder, and to suspect it’s the work of a serial killer.

In Connelly’s novel, Terry’s sense of responsibility to the dead woman is of a piece with the hard-boiled atmosphere. On the screen the sentimentality of that conceit is more pronounced. It needs a “Magnificent Obsession” air to it; it needs to embrace the sort of outsize melodrama that movies, because of their bigness, can do better than any other medium (except maybe opera) and, at their best, make transcendently emotional. That’s exactly the sort of thing Eastwood, whose directing style is as taciturn as his squint, can’t provide. (It was a problem in Eastwood’s “tasteful and restrained” film of “The Bridges of Madison County,” too; who the hell wants a restrained tear-jerker?) Terry’s sense of indebtedness never achieves the emotional heft it should; it’s just a task to be grimly gotten through.

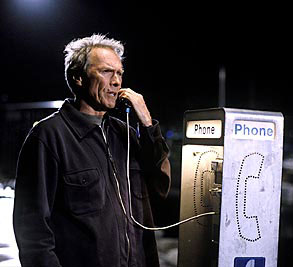

Eastwood’s coldness as a performer is no longer without skill. After years of action-movie heroes who are essentially asking us to love what cutie-pies they are, there’s something almost refreshing about Eastwood’s refusal to ingratiate himself, which makes the scenes where he plays the deadpan joker rather amusing. He’s now 72, much older than the character Connelly wrote, and that makes Terry’s predicament less urgent. It’s certainly harder for an older man to weather the physical insult of a heart transplant; on the other hand, a man with much of his life behind him doesn’t feel in as precarious a position as a man who has a transplant in his 40s or 50s.

Ironically, the biggest obstacle to Eastwood’s performance is his strapping build. The lines on his face and his patented wince make it easy for Eastwood to look like a man in pain. He’s very good at conveying physical discomfort. But the guy is so obviously fit that you never worry much about him. Eastwood keeps running his fingers along the scar in the center of his chest, and after a while it gets repetitious. There’s a particularly delicate manner in which people who’ve undergone transplants or bypass surgery or angioplasty carry themselves, hunched slightly forward as if to protect their chest. But Eastwood doesn’t seem to be much interested in playing the dirty bastard who gets the job done anymore, either. He will never suggest the reserves of feeling that John Wayne at his best did. But he’s got the authority and, if not decency, at least a sense of principled rectitude to make him a good hero for a hard-boiled mystery.

One of the reasons I wish Eastwood were a better director is his casting. Actors of color routinely pop up in prominent roles in his movies, and like Hawks, he doesn’t seem to be interested in women who are helpless little things. (De Jesús doesn’t have much of a role here, but she has a toughness that wins you over.) Eastwood doesn’t always do right by the good actors he’s been able to surround himself with, though his movies give the impression that he enjoys working with them.

As a boat bum whose rig is parked in the same marina as Terry’s, Jeff Daniels has a loose, shaggy presence that plays off Eastwood very well. It’s a little as if the character Daniels played in “Dumb and Dumber” had acquired a pair of sea legs. In his last scenes, when Daniels has to carry over that goofiness to a more dramatic situation, Eastwood lets him down by making him seem slightly hysterical. Daniels is one of those actors who is so casual that he’s constantly in danger of being overlooked. He’s been making movies for almost 20 years now and, as is often the fate of unshowy, believable actors, it might take some more time for people to realize (as they did with Gene Hackman) what great work he’s been doing all along.

As L.A. county sheriff Jaye Winston, a former colleague Terry turns to for help with the case, Tina Lifford plays her scenes with a quiet command. She’s one of those performers whose sexiness comes from the understated confidence she possesses. It’s obvious that Jaye and Terry were lovers but, nicely, Eastwood and Helgeland don’t spell that out, allowing us to read it from the grin the two break into when they see each other. That Winston is a black woman, and that nothing is made of that, seems as good an example as any of what’s right with Eastwood’s casting and approach.

Like the women played by Huston and De Jesús, Lifford’s Jaye merits respect for her brains, capability and toughness. The movie doesn’t condescend to her with anything as conventional as a scene where she has to prove her mettle by standing up to Eastwood — it’s just assumed she can. As much as Eastwood ever expresses pleasure about anything, you sense a flicker of gratification that he can work with actors who can hold their own against him. Lifford does it without breaking a sweat. Howard Hawks would have loved her.