Even the many who have fond recollections (or any recollections at all) of the '60s have heard just about as much as they can bear about the 20th-century decade that can't get over itself.

And yet, there is always more -- flashbacks, confessions, photos -- for those whose appetite for the past might never be satisfied.

Most recently, the era is plumbed in "A Long Strange Trip: The Inside History of the Grateful Dead," a 600-page memoir by the band's publicist, Dennis McNally. In truth, it's not just about the '60s -- the book hits 1970 about midway and continues on through half of the '90s. And McNally does not throw avid fans of the band, or the '60s, a mere bone. His history of the quintessential psychedelic band, and the strangely intoxicating waves it made, is an entertaining, picaresque, and exhaustive contribution to pop culture anthropology.

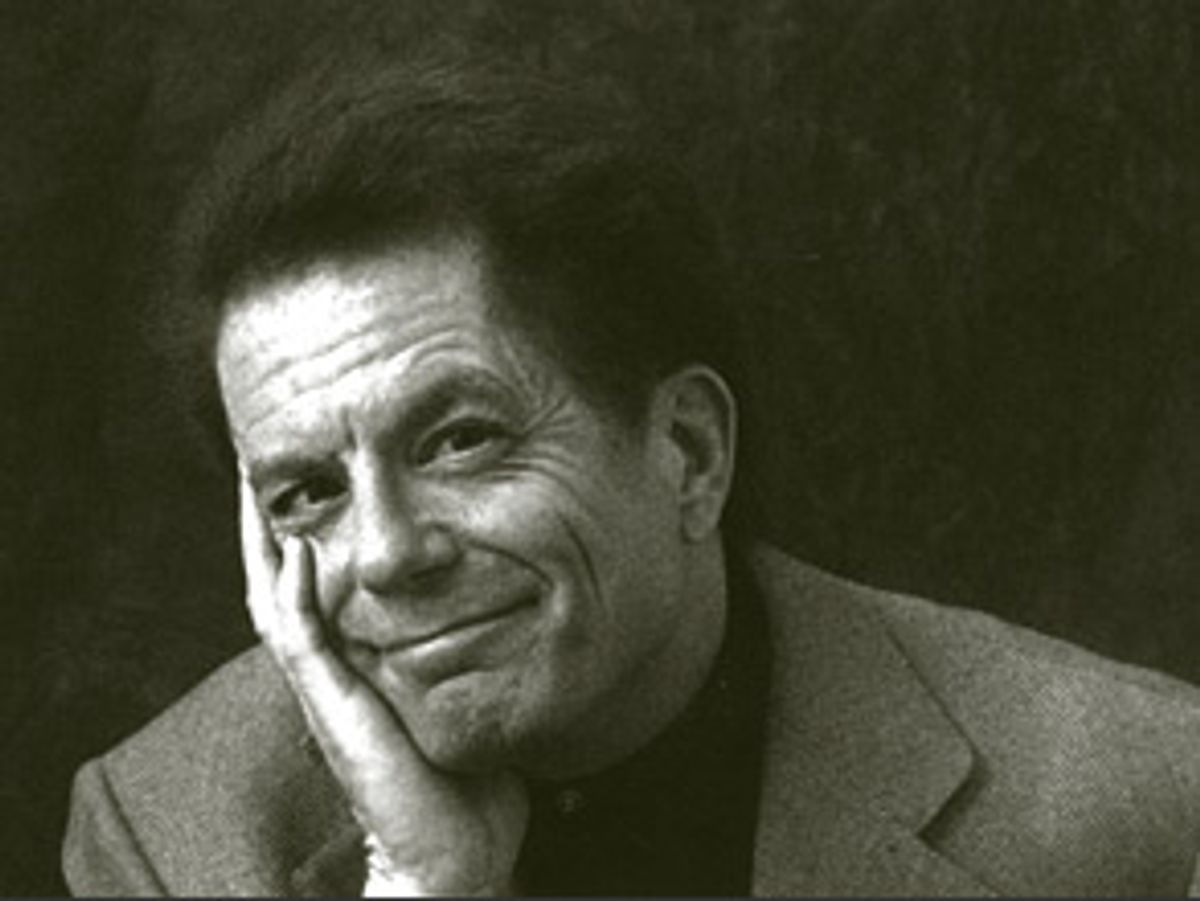

Of course McNally, a long-time Deadhead whose first book was "Desolate Angel: Jack Kerouac, the Beat Generation, and America," might be expected to write the ultimate Dead tome. With a doctorate in American history under his belt, he signed on as the band's official historian in 1980 and has been the Dead's publicist since 1984. As a result, he's had extraordinary access for decades -- to band members, crew, staff and hangers-on.

But "A Long Strange Trip" also suffers for McNally's proximity. He calls up remarkable detail for this biography, but the one thing he can't provide is distance. "Inside" is the operative word in this history: Some of the story is rendered in extreme close-up, offering tidbits that only diehard Deadheads will be able to fully appreciate. Yet a gloves-off critique of the Dead's vast, and vastly uneven, creative output will have to wait for another day.

That's not to say that this fat volume offers little more than a compendium of set lists and solipsistic cooing about the boys in the band. The wealth of anecdotes powering "A Long Strange Trip" is reason enough to take it for a spin. One of the most surreal images comes from McNally's tale of the day Sens. Patrick Leahy and Barbara Boxer invited the Dead to lunch at the Senate Dining Room: "As the group entered and sat at a table near the door," he writes, "everyone noted the presence of the 1948 segregationist Dixiecrat candidate for president, South Carolina's very senior Strom Thurmond. He, of course, noted Senator Leahy's party, and as he passed the table on his way out, turned to Garcia with the remark, 'I undastand you're the leadah of this heah organization.' Jerry Garcia and Mickey Hart shaking hands with Strom Thurmond was something the wildest acid trip could never have included."

While McNally doesn't hide his fondness for the band, this is no hagiography -- he's not timid about exposing the Dead's excesses and calling them on their shortcomings. After all, he says, they're "human beings, not saints." And there are several accounts that most anyone would find horrific -- Garcia's sad descent into heroin addiction, for example. As onetime Dead vocalist Donna Jean Godchaux put it, "As a whole, in general, the Grateful Dead is not benign." To which McNally adds, "Certainly not to its band members. It is a full-range experience, as Garcia was wont to say, with the good and the bad in perhaps equal measure. It is a world of theater and illusion, and there's plenty of evil around."

Following Garcia's death at age 53 in 1995, the remaining founders of the band agreed that the Grateful Dead would never again perform under that name. Good to their word, bassist Phil Lesh and drummers Mickey Hart and Bill Kreutzman would not appear together in a major concert for seven years, reuniting only this month, renamed the Other Ones, to play for an audience of 35,000 at the Alpine Music Theater in Wisconsin.

I caught up with McNally just a few days after he'd attended that concert. He was in London, promoting "A Long Strange Trip." When I phoned, he was watching a cricket match on TV.

To write "A Long Strange Trip," you essentially committed to doing a biography of most of your close friends. That seems like setting yourself up for incredible headaches. Why would you do such a thing?

When I committed to writing the book they weren't friends. I only got involved with them on a personal level when I began writing. I was already a Deadhead, became one in 1972, but I only met the band members after Jerry invited me to do the book in 1980. I began to meet them in the process of writing and then afterwards became an employee.

The thing about the Grateful Dead is, it's not the people on the stage. The Grateful Dead is this mysterious entity that is composed of everyone in the room, and instruments and magic and music and all that good stuff. The fact is that the members of the Grateful Dead and the crew and all the people that are personally involved in terms of what I wrote, they have this understanding that the Grateful Dead is something separate, and the only way to honor it is to tell the truth.

I think there's a consensus that this is not a hagiography, that it's an honest report. And the people involved are human beings, not saints. The only way to honor what the Grateful Dead is, is to tell the truth. I have yet to get a single critical remark about being too honest from anyone. That's a little unbelievable, but it's true.

They were such a strangely successful cultural anomaly, yet they're very much a part of what's become mainstream popular culture. The Dead went from being crazy freaks way out on the fringe to being a corporation with one of the country's most recognizable logos. How has their image of themselves and their place in the culture changed over the decades?

I think they've got a wonderful sense of humor about it. The irony is that because they did it their way, and because their way involved ignoring every rule in the book, and because the end result was this remarkable and completely unforeseen success, it's just the best joke ever. I end one chapter by saying something like, for once the Grateful Dead had the last laugh. And it's true.

They did things often for completely odd reasons. As an example, taping. They permitted taping for no other reason than that they didn't want to be cops. They were lousy cops, they were antiauthoritarian to the core, and it was too much work, too much bad vibes, too much everything. And, frankly, they were realistic and said, It's impossible to stop taping unless you strip-search every member of the audience, which ruins the atmosphere, of course.

But the serendipitous result was that they doubled their audience -- from the early '80s when they started to allow taping to until just before, say, "Touch of Grey," the audience increased tremendously. Why? Well, one of the reasons was they allowed taping, the audience responded to that by being ever more tightly bound to them because they were trusted. The teeniest percentage violated that trust -- the band's only request was that you don't charge money for these things. And almost no one did. And the end result was a greater intimacy, a greater trust.

One of the things that was very surprising was to learn that they were together a long time before they started making big money.

Absolutely, which is one of the best things, because that meant there was nothing to squabble about, nothing to divide them and they were all in the boat together. It was not until the mid-1980s that they started getting to the point where every show sold out. After "Touch of Grey" and "In the Dark" made lots of money, from then on they were quite prosperous, although not at a Michael Jackson or Paul McCartney level. They stayed close to their roots right through the mid-'80s.

Did the prosperity have a negative effect on them?

I don't think it helped any. Money divides. Or, rather than divides, it isolates. As they grew more prosperous, I don't think it had a particularly wonderful effect in the '80s and '90s. But it's also a function of having families and just having less time for each other. And they were definitely not as receptive to each other as people by the end. But how long do you maintain intimacy on an emotional and social level? They managed to do it for more than 20 years -- that alone is quite an achievement.

Some of the most interesting parts of the book were your accounts of how the Dead ran their business -- the meetings, the decision-making, such it was, the negotiations with record companies and concert promoters. It was often extraordinarily chaotic, but in the long run, it worked -- in spite of itself. I could see some business major doing a thesis on nontraditional business structures and using the Dead as the case study.

There have been a number of case studies -- by the Harvard Business School and others not so well known. And they all end up with the same conclusion: the Dead have very old-fashioned business values, which are: no hype; offer a product based on paying maximum attention to the important thing -- the sound system -- and a legitimate and honest concern for the audience. You don't do anything that isn't necessary. You do what's important and you do it well.

I know that sounds terribly old-fashioned, like Smith Barney: "We do it the old fashioned way, we earn it." Well, the Dead earned it -- they worked, they cared, they offered integrity. I know that sounds almost naive in this day and age, especially in the last month in America. Nobody ever cooked the books in the Grateful Dead, though of course we aren't a public stock.

The point is that they did very old-fashioned things in a very old-fashioned way, and it worked. It was a point of pride to sell tickets at a lower rate than everybody else was doing. I'm sorry, but I think -- and other people in the organization agree; I'm not alone -- the notion of selling the front row for $250 is disturbing and it doesn't feel right. The day that the Grateful Dead had to charge $30 a ticket, mostly because we had an extremely expensive sound system, but also -- this was on a summer tour -- we were paying the so-called opening act a great deal of money, people were upset. It's for real, because that's part of caring for your audience -- you offer value for the money.

Over the years, did you often find yourself getting just entirely fed up with all the confusion, the actual process of getting things done? Your accounts of some of the Dead's business meetings make them sound just chaotic as all hell.

Of course, about once a week. The whole point is, if you want a crisp organization, try a leader-dominated, vertically integrated setup, but that's not the way the Dead worked. Every band member undoubtedly felt the same way at one time or another, except maybe Jerry, 'cause Jerry set that tone. He did not want it to be organized. He wanted to trust that anarchy -- no given leader, whoever felt strongest would lead at a given moment -- he wanted to trust that that could work, and it did work. He said once in an interview, "It's not like G.E., but it works and we have a lot more fun."

You refer to the band members as emotional cowards. Can you explain what you mean by that?

Well, you know, again, Jerry set a certain tone. He did not want to be responsible for running things. And when you run things in a business organization, which, among other things, the Grateful Dead was, that generally means that you hire and you fire. And while hiring is fun -- that's welcoming in -- firing is very painful.

There were times -- looked at objectively and from the outside -- perhaps there were people who should have been removed long before they were. There were a couple of moments when the Grateful Dead finally made a decision that so-and-so just wasn't working anymore. And, you know, they said, "OK," and they turned to the manager and said, "You do it." That's what I'm talking about. They deflected. They didn't want to cope with that. But the band members read every word of this book and they saw that account and I didn't hear any argument from them.

They took a lot of drugs, especially LSD. You don't hide that fact in the book.

You know, we live in an era in which all drugs are equally evil, and that's not so. At the very least let's make intelligent distinctions. If you can find me somebody who's died from marijuana, if you find someone who's become addicted to LSD, show me that person. It's not appropriate to describe it in those terms. I've seen as much drug abuse and drug damage as anybody needs to. I don't advocate them, but I do wish that we'd stop the bullshit of seeing them all as being equally evil, and start talking about them intelligently.

To what degree do you think taking acid spurred the Dead's creativity and to what degree was it a drain on their energies, both intellectual and emotional?

As far as LSD goes, I don't know about any drain during their period of intense LSD use, which was primarily very early on in their career -- we're talking about a few years in the '60s; it's not like Jerry Garcia, or anybody, was taking LSD in the '90s. It's a physically depleting thing. It's definitely an intensification of your reality and as such it's definitely got a physical consequence to it. As a result, people don't take acid night after night; it won't work night after night that way.

What it did for them most remarkably and most importantly -- in the Acid Test period, which, by the way, was two months -- was redirect their notion of what they were up to, and it made them understand that the audience was not separate from them, but was part of their experience, that they were partners. And that, in fact, the Grateful Dead was not six guys on stage, but everybody in the room and the instruments and the sound system.

You think it strengthened their emphasis on inclusiveness?

Oh, absolutely. I mean, if I can generalize, and it's dangerous about LSD because everybody experiences it differently, but one of the common conclusions people come to is a sense of the oneness of all life. That's a fairly common reaction ... It worked in a performance setting because it destroyed the notion that "We're the band, we entertain, we stand up here, and you are cows with wallets and you absorb what we give you as musicians."

And what they decided was that there was loop of energy -- it starts from the string and goes through the sound system and out into the audience and comes back -- which is why they were notoriously a wonderful band live, frequently magical live, but in the studio without that feedback they were so-so. To quote Mickey Hart, "We're not in the entertainment business, we're in the transportation business: we move minds." It's a good line and it's accurate.

You delve into the psychology and emotional life of Jerry Garcia considerably more than you do any of the other band members. Would you have done that if he were still alive?

That's a good question. Possibly not. The point is that Jerry Garcia was the largest personality on that stage. If you had somebody from Mars come down and walk into the room where all the Grateful Dead were sitting, they would see that Garcia was a slightly larger-than-life personality and he was charismatic. He refused to lead, but by some peculiar gravitational example.

But in the end, yes, you're probably right. Because he died, that did end the Grateful Dead, the Grateful Dead as a touring band. And that obviously had a consequence to my writing.

It seems that the Dead's greatest shortcoming may have been that they -- an exceptionally close-knit group of people -- utterly failed to save the central personality in their group, Garcia, whom you've described as the Dead's "emotional center." How could that happen? How did he lose his way so irreversibly?

Well, I can only refer you to the book and say, Look at the personality that develops in the 1950s.

He was a man who harbored a lot of pain that he never dealt with, it seems.

Right, he didn't deal with it. And unfortunately he ended up with self-esteem issues; he did not choose to take care of himself. Saying, "Well, the band should have saved its leading personality": Well, they tried, they did try. He had to save himself. And, as I say in the book, along with his incredible intelligence came an incredible ability to refuse to listen to anybody else if he didn't want to. And you have to want to be accessible to that sort of advice and to be able to change.

In the end, remember, he made the decision to be clean, to step toward the light if I may be a little poetic, and then his body said, "Well, thank you, good decision, we're leaving now." And that's what happened, he died of a heart attack.

The afternoon of his death, I looked at the manager and we said, "You know, he made that commitment [to get clean and sober], so it doesn't feel as awful as it could." Because, you know, we sweated and worried and freaked about him for years, extremely painful. Again, drugs were like a side effect. It was simply neglecting his body.

He had a raft of physical problems.

Right, which he completely refused to deal with, refused to see a doctor, to do all that bourgeois stuff that most of us want to do because most of us want to live to a healthier age. If it hadn't required a lot of effort, he probably would have, too, but he wasn't ready to make that choice. And that comes out of deeply rooted personal issues that no one in the Grateful Dead could reach no matter how hard they tried.

You just saw the Other Ones, a band that includes the remaining original members of the Dead. Do you get the sense the musicians are still able to revisit that place of communal fun or have the rigors of the last few decades made that kind of abandon a thing of the past?

On the Sunday night they played two shows. They played a really brilliant second show. They'd rehearsed for three weeks, then they'd been out with other bands. And, really, the first night was almost a rehearsal in some ways, though brilliantly played.

I sensed a whole other level by the second night. And I can't imagine what it's going to be like on this tour ... When they finished on Sunday night they lined up, put their arms around each other, took a bow. The audience wouldn't let them go. The band went into a little circular huddle and they began pogoing -- 50- and 60-year-old men, along with a couple of younger accomplices, were pogoing. It was pure joy. But no, I think it took seven years, an interestingly mystical number, to recover from the pain that they felt from watching Garcia slip away from them, no matter how hard they tried. But the fun's still there, very much.

Chapter 49 of "A Long Strange Trip" is a list of various band members and others answering the question, "What is the Grateful Dead?" I'd like to put that question to you, "What was the Grateful Dead?"

The Grateful Dead was a mythical beast that made a whole lot of people happy, including its musicians, but also millions of people in the audience. And that gave a lot of people the belief -- and not just the people who lived in tie-dye in the parking lot, but also a whole lot of people ranging from Al Gore and Sen. Pat Leahy to Owen Chamberlain, the Nobel laureate, who used to sit between the two drummers because he said it gave him interesting ideas -- that, to [paraphrase] Dylan, you can live outside the law, be honest and get away with it. Or, to quote Phil Lesh, when the Dead were welcomed into the Rock 'n' Roll Hall of Fame, "Sometimes you don't merely have to endure, you can prevail."

Shares